They usually walked up our drive heralding their arrival with the baritone melody of their lyrics, accompanied by the strains of a deftly played ‘sarangi’, conjuring up images of minstrels that must have strolled the streets of Lahore centuries ago. Their mutual resemblance suggested that they were siblings as did the harmony and resonance of their singing, the uniformity of their white kurtas and ‘dhotis’, complimented by ‘pugrees’ of the same color and worn out ‘desi’ footwear. The ‘singer’ half of the duo was sightless, the cause of which lay, perhaps in his heavily pock marked (yet handsome) visage. They would stop in front of our verandah and begin their performance with a couple of devotional songs including one, the opening lyrics of which, still linger in my memory – “Sub se achcha naam piyara ya Rasool Allah ka”. They probably enjoyed performing at our house, as they attracted an audience of both young and old (including my grandfather), immediately on arrival. One detected a strange dignity in the pair, by the way they carried themselves - never asking for money or anything else in return. This was perhaps the reason that they were handsomely rewarded from every home (including the Young Women’s Christian Association Hostel next to our house). As I grew up and left home to take up a career, news arrived in one of my mother’s regular letters that the duo had stopped coming, never to be seen or heard again.

Our ancestral houses inside the walled city were approachable through a narrow street that opened out into a brick paved expansive courtyard. We often took this route on foot, after parking the car outside Mori Gate, when visiting our grandmother (my grandfather’s younger sister), aunts and cousins. On entering this street, visitors became aware of sharp tapping sounds, which got louder as one came abreast with their source – a group of men sitting cross-legged in an open fronted room, merrily hammering away at something placed on top of small wooden anvils. These were the ‘silver wafer’ makers, the core of a unique industry that made ‘chaandi ke waraq’ for adorning our traditional desserts. The rhythmic pounding of their hammers was designed to gradually beat a tiny strip of silver foil into a wispy wafer. It was perhaps the wooden hammer and anvil that made the sound acceptable – even enjoyable, if one had an ear for rhythm. I am told that these wafer makers and their signature ‘tapping’ has now become rare and may one day even be silenced forever.

Another sound that I long to hear is the musical twanging of the ‘panjeera’. This was a large sized contraption, which looked like a stringed instrument, but was used to fluff used cotton wool for recycling into quilts. The advent of synthetic fiber speedily pushed cotton wool out of the picture (at least in urban communities) and with it the familiar sight and ‘music’ of the ‘panjeera’.

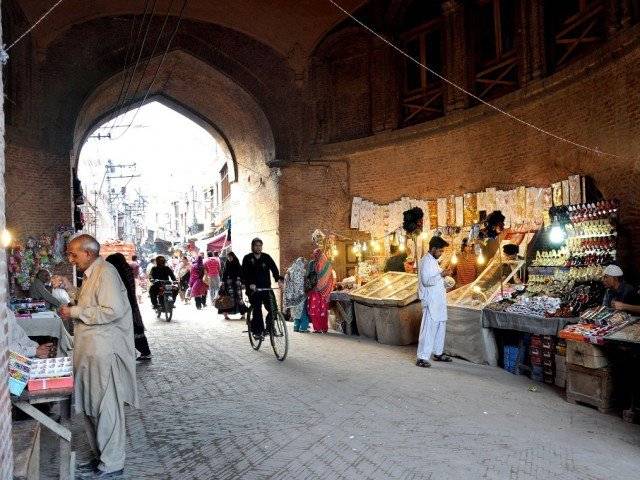

Visitors shopping in Anarkali of old were often intrigued by a loud throaty voice chanting “Mooli ka Namak”. The source of these words could soon be detected through the crowd - a middle aged man, pushing a bicycle with a tin rectangle hung in front. This sign bore the image of something resembling a white radish, underlined by the words ‘mooli ka namak’ and a short description of what this magical powder could do to rectify digestive disorders. Sadly enough, the ‘namak’ continues to be sold in Lahore’s celebrated bazaar, but gone is the original source (and the sound), which in my reckoning symbolized the spirit that made Anarkali what it was.

The ‘chana jor garam’ vendor, had perhaps staked his claim to Neela Gumbad. He sold spiced ‘channas’ in newspaper cones and advertised himself with a musical voice, lent color by the ‘jingle’ – “Chana jor garam baboo, mulayam mazedar, chana jor garam. Mera chana burra he aala, is ko khai Madhobala, Nargis lagay hai us ki khala, chana jor garam”. The lyrics of this rudimentary commercial were perhaps picked up from an old pre independence movie and adopted by other vendors selling the product, but none matched the ‘sanctity of scale and melody’ as practiced by the man in one of Lahore’s most well-known spots. Sadly enough, this particular individual can be heard no more.

I was therefore delighted, when a friend informed me that somewhere within the dark recesses of Radio Pakistan (now Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation) archives lay a tape containing these sounds of yore, waiting for some passionate and creative mind to storyboard them into a nostalgic series that has every chance of becoming a hit. I now eagerly await for this to happen.