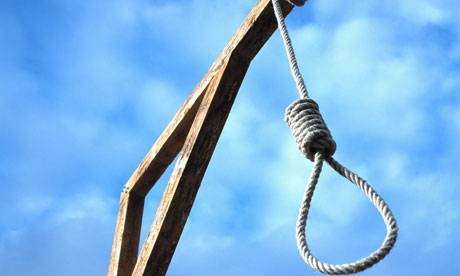

Earlier this month, the Army Chief “confirmed” the death sentence for six TTP militants, who had been tried in the military courts, recently established under the 21st Constitutional Amendment, and the Pakistan Army (Amendment) Act, 2015. On Thursday, these death sentences were suspended by a seventeen member bench (Full Court) of the honorable Supreme Court of Pakistan, in a petition filed by the Supreme Court Bar Association (SCBA), which challenges the constitutionality of the amendments made to the Pakistan Army Act, 1952, and seeks clarification of the 21st Constitutional Amendment, on the grounds of fundamental rights and due process of law.

The decision of the honorable Supreme Court, on the one hand, is being hailed as a (minor) victory by human rights activists and most of the legal fraternity, while, on the other hand, it is being criticized by those who view ‘military justice’ as the only real solution to terrorism in this land.

The tussle highlights an inherent disconnect in our societal ethos, and brings to surface the ideological issues that are brewing at the core of our national identity.

The first set of issues, voiced by those who value the ‘results’ more than the ‘process’, follow a familiar trajectory: Is ‘law’ more valuable than ‘life’? Should those who murder our children be afforded the respect and compassion of our laws? Does the constitutional empire of fundamental rights extend even to those who seek to destroy the Constitution, and all that it stands for? Does the State have a responsibility to protect those who seek to destroy it? Should law come to the rescue of those who are lawless? What good would it be to uphold a law that protects those who have a gun to our head? Why wait for ‘conclusive’ evidence, when it comes in the form of a suicide attack? What good is a smoking gun, if it comes in the form of a mushroom cloud?

The counter narrative, emanating from (leftist) human rights activists, argues an equally passionate trajectory: The law is not an instrument of convenience, to be applied at our leisure. Its letter and spirit becomes even more imperative in times of exigencies. What good would the law be, if its command dwindles in the face of adversity? How better can we test the tenacity of our constitutional protections than by applying them to the very people who offend its fabric? What would be the virtue of ‘equality’ and the ‘due process of law’, if these are only applied, timidly, among a select few? In fact, is it not our brutish desire and animalistic instinct of revenge that the law is designed to protect against? And if so, should the command of law, and its due process not be even more jealously applied when dealing with the alleged terrorists?

The answers to these questions cannot simply be extrapolated from legal doctrines. Nor can they be conjured from heated moments of passion. These issues rest at the core of who we are as a people, and who we wish to become as a nation. Yet, sadly, there is no national consensus concerning this ideology.

It is one thing for private citizens within the country to have discordant views on these questions of grave implication. It is quite another for institutions within the State to be contentious about the same issues. At the moment, it seems that the bar and (probably) the bench, oppose installation of the military courts, as a ‘parallel judicial system’. Supporting their point of view, albeit for very different reasons, is an alliance of the right-wing religious political parties, their supporters, and a fraction of the leftist liberals. On the other end, is the narrative of the security agencies (military and civilian), with support from most of the mainstream political parties, and a large section of the civilian society that has been a victim of the ‘mindless malice of violence’ (Robert F. Kennedy). This constituency claims to value ‘human life’ over the nuances of law, and backs their contentions with footage of blood-soaked corpses, and a stream of patriotic taranas.

Caught between these clashing ideologies and conflicting passions, Pakistan remains a State where Mumtaz Qadri and Zakiur Rehman Lakhvi continue to face their trials for murder, while being showered with rose-petals in the courtroom. We are a nation that laments the judiciary’s inability to convict the terrorists, but seeks judicial intervention to stop their executions. We are a country that hates TTP, but chants slogans in favor of the ‘liberal’ lawyers who petitioned the court to stay the hangings of TTP terrorists.

This game of cat and mouse has gone on for far too long. Viewed through the lens of either law or logic, each of the conflicting philosophies (the human rights narrative, and the national security narrative) has its merits. But it is time that we stop taking half measures in either direction. Individual dissent aside, it is time that the State institutions in Pakistan – the polity, the military, and the judiciary – arrive at a deliberate and concerted strategy, which is constitutional as well as practical, in countering the plague of extremism.

The stay granted by the honorable Supreme Court of Pakistan, as an ad-interim measure, should be seen as an opportunity for all stakeholders to work out a unified approach that is true to our constitutional ethos and democratic spirit, while still addressing (comprehensively) the existential threat of terrorism that is faced by our country today.

Nations are judged by the manner in which they rise to meet the challenges that history places upon their doorstep. This is our moment. Let us stand up and be counted as a formidable nation.

Friday, April 19, 2024

Civilian or khaki justice?

The writer is a lawyer based in Lahore. He has a Masters in Constitutional Law from Harvard Law School. He can be contacted at saad@post.harvard.edu. Follow him on Twitter

KP minister briefed on issues about sales tax on services

April 19, 2024

64th anniversary of freedom fighter Mirzali Khan marked

April 19, 2024

893,000 students appear in SSC exams in KP

April 19, 2024

Saudi govt shows interest to fund two road projects

April 19, 2024

Moot notes diabetes, blood pressure on the rise among youth

April 19, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Wheat War

April 18, 2024

Rail Revival

April 17, 2024

Addressing Climate Change

April 17, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

Tax tangle

April 18, 2024

Workforce inequality

April 17, 2024

New partnerships

April 17, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024