Madrassas: the enemy within

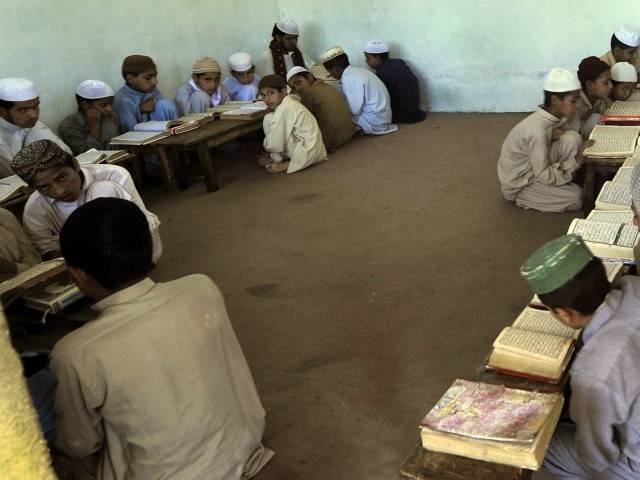

Interestingly, if there is one segment of the population which has complete freedom of expression in Pakistan, it is the Muslim religious theocracy – they can say whatever they like - there is no curtailment, there is no retribution and there is no blowback to them from the state. The rest of us pay the price of what the old adage says, ‘Little knowledge is a dangerous thing’; when young men and women take the name of Islam – the little they know of it—to create havoc. Chaudhury Nisar’s recent statement in which he assured us only 10 percent of all madrassahs are linked to extremism and terrorism means that we have around 300,000 madrassah students that could become potential militants. Even if they don’t blow themselves up, the limited education they receive, keeps them inside a primitive mindset and disconnected from the rest of the world, and thus remain potential sources of instability. We need to save these children!

Under the National Action Plan, we are once again being promised that this is it, this is when something will happen, this is when heads will roll and accountability will set in. Madrassahs’ extremism roots will be uprooted and the sacrifice of those innocent children and teachers will not be forsaken. Yet, for change to be implemented, there has to be will and consistency of action by the state on many fronts; registration of madrassahs, curricula expansion and reform, curtailing the set-up of new madrassahs as well as monitoring funding and in particular removing foreign funding are immediately needed.

In Pakistan, madrassahs have sprouted up in all shades and forms and mushroomed without much interest shown by the state. In 1947, Pakistan had less than 300 madrassas. By 1988, it had less than 3,000 and now we have around 26,000 registered madrassahs and estimates of another 4,000 to 10,000 unregistered ones. Estimates on the number of students in these vary from 1.5 million to 3 million, the latter would make it around 10 percent of all children enrolled in education. Registered madrassahs fall under five boards, Wafaq-ul-Madaris Al Arabiya has the largest number of madrassahs around 80 percent, Tanzim ul Madaris has around 10 percent, Wafaq ul Madaris Al Shia has around 500, Wafaq ul Madaris Al Salfiya around 500 and finally Rabita tul Madaris has around 400 madrassahs.

Last time, a serious effort was made to register madrassahs was in 2003 under the Pakistan Madrassah Education Board, but it was unsuccessful partly because it was seen as a foreign agenda. This time around, the government needs to make it clear from the outset that this is a Pakistan driven agenda and take the Pakistan Ulema Board and the religious parties on board to explain the few rotten apples are giving all madrassahs a bad name and needed to be weaned out.

Most madrassah students are only taught religious subjects but this has meant the qualifications gained are generally viewed as being worthless outside the religious sphere with over 90 percent of these students going on to become maulvis or teaching religious studies or Quran to other children. The only slight acceptability of the religious degree came after General Musharaf in 2002 introduced the degree qualification in order to stand for elections – this left most religious parties and their leaders out of the loop since they mostly had religious qualifications- at that time, some equivalence of the two systems was created for political purposes. The government needs to create specific projects that help these religious students gain ‘better’ or more diverse opportunities through giving them the facility to enrol at one of its vocational and technical colleges that have been set up or through persuading corporates asking them as part of their CSR portfolios ‘take a madrassah student’ internships.

After 9/11, Musharraf was given foreign funds to support work being done under the Pakistan Madrassa Board Ordinance; aiming to bring madrassa curricula in line with the country’s educational system. However, there was much resistance from the religious leaders who not only saw this as an external agenda but also resisted the loss of authority. In 2010, under the PPP government, the five Wafaqi boards signed an agreement to introduce curricula reform – the Wafaqi boards blame the government that it showed no interest in pursuing this afterwards.

It is clear that madrassah students need a wider educational curriculum so that they can gain the maximum opportunities that the society offers and the Wafaqi boards are also coming to understand this. The government now needs to work expeditiously and build upon this. For example, in the UK, muslim schools teach Arabic and islamic subjects but they also have to teach general curriculum subjects such as English, math, science, humanities, art, drama, physical education and religious classes have to encompass discussions on comparative religions. And if they are not up to standard, then its ‘tough luck.’ They are closed down by OFSTED (Office for Standards in Education). Upon introducing the curricula, thereafter state educational inspectors should certify that the proscribed subjects are being studied up to the required level. While we are at it, lets ensure that the texts they are studying from emphasize the values of tolerance and acceptability of other people and ideas.

Madrassahs exist because there is demand for them. There is an unmet need for education especially for the poor that they are providing. They also give their students free food and lodging as well – sometimes even basic health coverage. These are all basic requirements that the government should be fulfilling; basic health and education coverage for its citizens. If they decided to make this a priority instead of white elephant projects we may find less demand for the madrassahs. In the meantime, we need to ensure that we are able to find any that have fallen into the militant camp and curtail further growth of madrassahs. This will be done when the state enforces and ensures compliance by madrassahs on laws pertaining to them.

Madrassahs should be financially audited - where is the money coming from and going to? We need to speak to our ‘friendly’ countries and ask them to stop sending money to any kind of religious seminary. We need to make laws that outlaw such funding. In addition, money laundering and terrorist financing laws need to be vigorously enforced. Despite this a lot of money will still arrive in suitcases over our porous border, but stricter financial auditing of madrassahs will curtail some of this. Here is a thought to keep in mind next time you reach into your pocket or handbag: the majority of funding to madrassahs is domestic funding and comes through charitable donations and zakat.

We have a history of unsuccessful reform attempts in this area. Now is not the time to make this into an argument of the ‘religious them’ versus the ‘rest of us’ – but for all of us to join hands against the few who no longer want to be a part of us.

Najma Minhas is a Director at Governance & Policy Advisors. She can be contacted at np@gapa.com.pk