It is now cliched to say that Pakistan’s education system is flawed, possibly beyond repair. Everyone knows that, acknowledges that as a fact and then goes about their business as if nothing is wrong. We seem to be content that an overall literacy rate of the country is 57%, with gross disparity in genders. It is a fact of life. But we have heard enough about the problems of the out of school kids, about the children that drop out after primary level education and about people who can’t even afford education, even in the very cheap public schools for various reasons. Today, we will talk about the other half of the equation.

Accepting that nearly half of Pakistan is able to read and write is technically correct. The problem with that is, that it is easy to verify but doesn’t reflect the essence of education. You cannot easily test if half of Pakistan’s populace actively understands what they read or write. And that is where we fail completely. Among the 57% of people in Pakistan who can read and write, only a fraction of them can actually write on any given topic, or understand what they are being taught. This leads to a large number of questionably educated people, with post-graduate degrees but who still have trouble writing a research grant proposal.

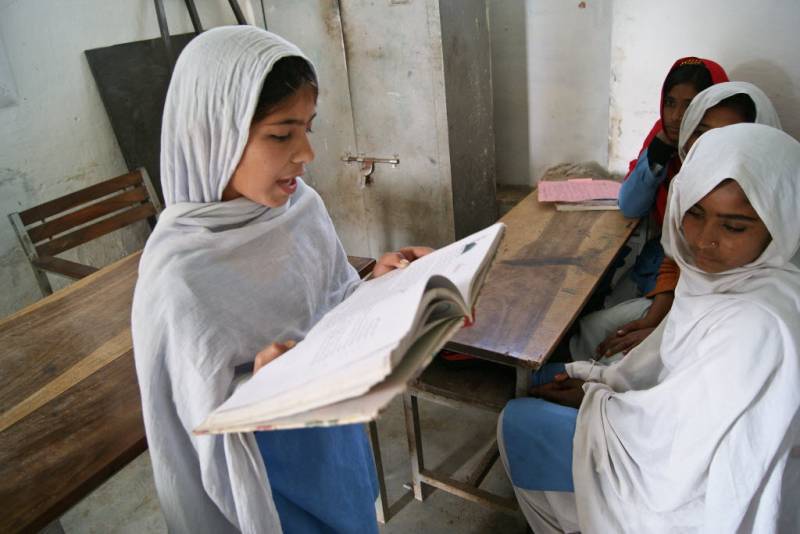

The causes are manifold, but it boils down to the simple fact that our education system is grounded in rote learning. The system rewards rote learning, and even if it once allowed independent thinking, it does not anymore. The current crop of teachers were taught the same syllabus and the same methods and they refuse to budge from them, leading to them expecting the same answers they were given from their students now. This should not even be acceptable in social sciences and arts, let alone science. I can tell from personal experience that even a decade ago, students were trying to memorize math exercises instead of learning how things work, and even if the question on the exam had a single different value, they would trip and forget.

According to a UNESCO report, when the students of sixth and fifth class were asked to read an essay, 94 percent and 68 percent students could not read it. This is a very sad state of affairs. Yet, if you look at the results of all the intermediate and matriculation exams in the recent years, you see a steady rise up to a point where anything below a 90% grade marks you as an undesirable. This race for “more marks” motivates people to forego understanding the subject material in favor of “gaming the system”, rote memorization, predicting question patterns and outright cheating. I ask you, what use is a memorized essay if you cannot express a simple concept of your choice in a single paragraph when asked?

In a country where asking questions is considered shameful, this state of affairs is not surprising. However, asking questions and finding answers is the basic reason of educating people, not the regurgitation of facts memorized without understanding. We have to change this part of our education system, focusing on exploration, understanding and originality, rather than rote memorization and “number game”. The education system needs an overhaul, no matter which way you slice it, and we should get to it, before it’s too late.