A few days ago, I met Michael Bruckner, an Austrian musician who visited Pakistan for a brief week, along with three other friends in their music group called Nifty’s. They held concerts in Karachi and Islamabad, including with some Pakistani ustads. Sometimes, fusion concert sections are not really ‘integration’ of Eastern and Western sounds; each plays what they know and the sounds become parallel, not quite a fusion. This time, though, the artists showed that they had fun playing together and borrowing from each other’s deep rhythmic sounds. It was joy and pleasure for the musicians and for the audience in the large PNCA auditorium in the capital.

My role was just to listen and observe. That is what my article is about today, notably trying to appreciate and understand what we see and hear.

I am a social scientist and I have spent much of my time teaching and writing so others can learn what I think is important. Hence, more than many others, I probably need to de-learn many things, so that I can give room to more neutral observation and give space or new learning. I do like people with opinions, but I also like people who try to listen before they speak. I also like if people say, “I never thought of what you told me, and it was fascinating to hear. Please tell me more so that I too I can understand and appreciate a bit better what you seem to like so much.” And I in turn, must say that when others generously tell me new things.

This is just a natural curiosity for what we don’t know, you may say. That is true. But often we are not curious; often, we just want to tell others something so they can see how clever and smart we are, not so that necessarily so they can learn and understand what we know. It is even said that teachers many times do the opposite of what we say and want to do, with good help of formalistic and static textbooks. Then teachers reduce the children’s and young people’s curiosity, fantasy and creativity – their ability to observe and appreciate leaning something new. In workplaces and elsewhere in society, we often experience the same; we are not given room to be innovative and alternative – and this is in a time when we are also told that the ‘body of knowledge’ will change fast and grow tremendously in volume – with a major portion of what we learn in young age will be obsolete by the time one reaches my age, en route to retirement.

Allow me today to defend people who are senior citizens, though, because we may indeed be able to show young people some of the ways they can take in order to learn to observe; enjoy being creative; being proud of going their own ways and doing experimental, alternative and outrageous things. They must be encouraged to observe and innovate, not always judge and feel being judged. We who are getting on in life may have regrets when we too often just conformed and did what was expected of us, although some of that is also necessary.

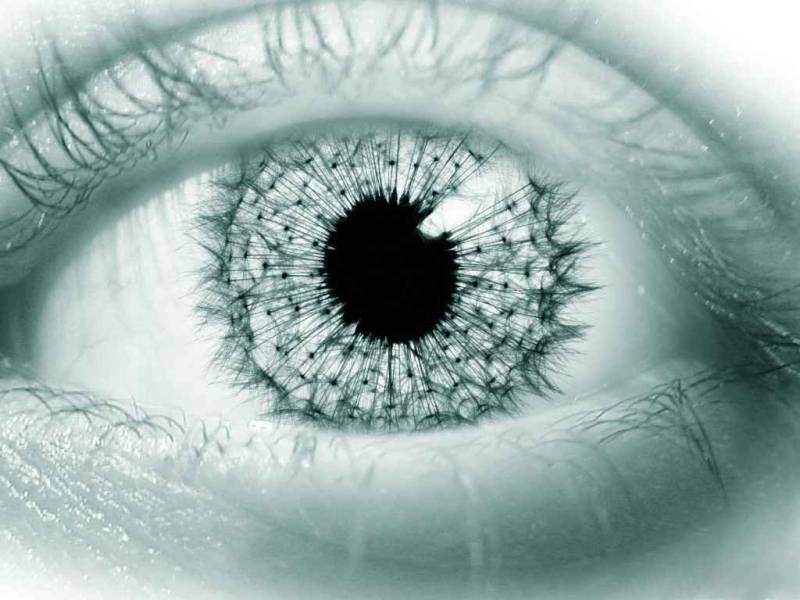

Michael, my newfound Austrian friend and his fellow musicians, also showed me something else, a display of ‘big pictures of small things’, as it was announced at the concert, notably photos of ants and other insects, displaced in the foyer outside the concert auditorium. The artistic photos were taken by Michael, who enthusiastically explained that we could find beauty in the least expected things and places. But we had to look and observe a bit more keenly than just taking a quick glance in passing at nature, people and places.

No surprise, Michael Bruckner is into more art and human communication than music and photography; he also dances, climbs mountains, and paints a bit, he said. At the same time, not being an ‘artistic freak’, rather looking just like any other decent young man, engaging with guests from many walks of life, ages and cultures in a foreign land. I am sure he observed, too, as we spoke with him, and learnt from the whole event.

Artists and others in creative fields know full well what I write about today; they know that they translate what they see and hear, mould it through the medium and hands, shaping it into new forms.

Fiction writers, even social scientists, historians and others in the humanities, indeed literature analysts and philosophers, are said to hold up a mirror to us so we can see who we are and the world and time we live in. Nowadays, it is common that writers mix directly their own experiences with fiction; they tell about their own backgrounds and lives; their childhood, marriages, divorces, successes and failures, who to blame and honour for who they are, and so on. They not only observe others; they also observe themselves and those who are closest to them. This is almost a new genre in literature. In future, I believe that even researchers will mix fiction with strict research, and it will make us all wiser and understand the world around us better. It is a renaissance for humaniora and the old philosophical sciences, where we get more space to observe, think and debate, not in order to prove we are right, but rather to shed light on issues, things, people and the world around us, as it was, is and can be.

How can you and I become better observers? First, it is to be aware of the importance of observing; second, it is actually doing it and resisting from letting one’s own baggage coming in the way of seeing and learning new; and third, it is engaging with those we observe, drawing some lessons from the way social anthropologists have always emphasised ‘participatory observation’.

In Pakistan, we have distinct economic and social classes, and a number of rigid rules for how to live and behave. The upper classes live their own sheltered lives while the majority of the people lower down on the ladder, who actually do most of the work in the land, are cut off. Such stratification form hurdles to creativity and innovative development. Through observing and learning from each other, we can change these structures. Thus, observing and learning are not passive and neutral only, as I said above, they can indeed lead to advancement.

This week, I was made aware of works by a brilliant, young American economist by the name of Raj Chetty, who was at the University of California as a professor in his twenties, and now, entering his thirties, he has moved to Harvard. He stresses that if you want your children to do well as they grow up, don’t let them live in sheltered compartments; it is those who live in diverse and mix communities, where people not only see each other, but observe and engage with each other, that do better later in life. The upper class will do alright (or poorly) even if they live behind high walls and in shelter bubbles, but they are not really important. It is the rest of us that are important, and we must live together in our everyday lives, black, white, brown, yellow; well-to-do and poorer; immigrants, refugees, indigenous and others; educated with degrees and skilled people with less formal papers; and so on.

In my daily life in Islamabad, I want to boast of every day talking to people from all steps of the social ladder. I don’t do it to be kind or saintly; I do it because it gives me pleasure and new knowledge. Often, I am more impressed by ordinary people than those who are higher up, yes, and more like myself. But I must be willing and able to listen and observe, to be able to learn. I believe that in future, our understanding of the ‘art of observing’ will be more important than Internet surfing and new technologies.