Is qawwali a genre of music? No, because music is only one of the four essential elements of qawwali. Knowledge, awareness and gnosis, along with music, constitute qawwali. That and many more gems of information were heard recently in a presentation titled Exploring Qawwali by music aficionado, Dallas-based Ally Adnan, organized by Kuch Khaas in Islamabad –on the second floor of the iconic London Book Company in Kohsar Market, a new and central venue for cultural and music related events in the capital. Ally’s talk was a treat for classical music buffs in the city, and a wonderful opportunity to learn about the origins, history and evolution of one of the sub-continent’s most definitive music genres. Ally’s knowledge of classical music is well-known and his ability to share his thoughts succinctly and simply makes the experience appreciable and relaxing. He was joined by Ghayoor Moiz Mustafa Qawwal, (the sons of the legendary Fareed Ayaz and Abu Mohammad Qawwal), and whose qawwali renditions interspersed throughout the talk were the musical mode of this pleasurable learning experience.

Ally Adnan

Ally Adnan

Ally’s presentation began with the origins of qawwali, and it was an eye-opener to learn that its antecedents date to,at least, 32 centuries ago, when the genre existed in various forms: As samaa, the several rituals involving music, dancing; as zikr, the devotional practice of chanting divine names in rhythm; and as Vedic chants, the process of which – chanting mantars – is the oldest oral tradition in existence. Even more fascinating to learn was that qawwali, can be, but is not always about God, can be about religion, but doesn’t have to be, but it is always, always about love. It is a well-known fact that as Muslim conquerors made their way to the subcontinent from Central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran and Turkey, scholars, philosophers, clerics, ascetics and Sufi saints followed in their wake – they used the mode of qawwali extensively to attract non-Muslims to the faith.

From explaining the basic elements of music – sur, raag, lay, and taal – to the adherence of the rules of raag and taal in qawwali, the talk moved to the evolution of qawwali during the period of Hazrat Amir Khusrau (1253-1325 AD),and to the specific Khusravi raag and taal, as well as the accomplishments of this music maestro who gave us the form of qawwalithat we hear today.

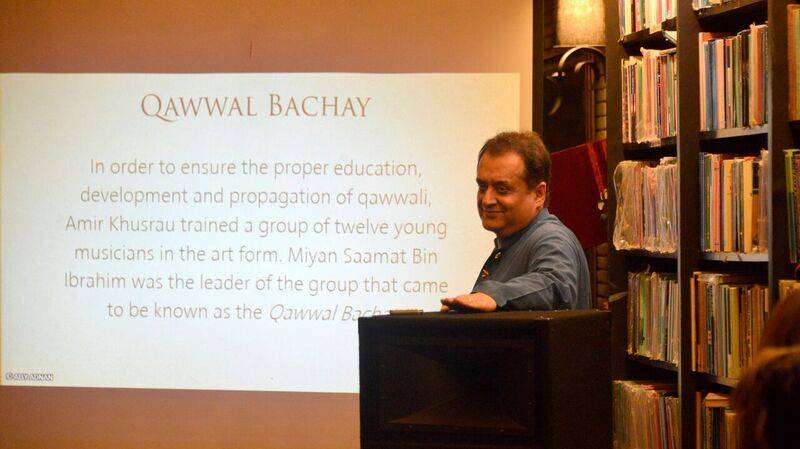

Ally narrated an important incident from the court of Allauddin Khilji, the second ruler of the Khilji Dynasty (1296-1316) where the famous master musician from South India, Gopal Naik, in a bid to assert his musical prowess and superiority in Khilji’s court, posed a challenge to all contemporary musicians to respond to the songs he had composed in 28 thousand lines of verse. Hazrat Amir Khusrau’s response to the challenge was a stunning composition of just 28 lines of verse, presented by twelve young musicians he had trained himself, led by Miyan Samaat Bin Ibrahim, all of whom came to be known as the Qawwal Bachay. Khusrau’s 28 lines of verse, not heard before in their entirety in the qawwali range of modern qawwali artists in Pakistan was presented by Ghayur Moiz Mustafa Qawwal that evening, a stunning composition that must be brought back to the qawwali repertoire of today.

It's important to note here that the school of music established and followed by the scions of the twelve musicians is known as Delhi Kay Qawwal Bachon Ka Gharana, and that Ghayoor Moiz Mustafa Qawwal are the direct descendants of this gharana; like their ancestor Ustad Tanras Khan at the court of Bahadur Shah Zafar, and the most recent, their grandparent Munshi Raziuddin Qawwal.

Another unique composition that Ally Adnan researched and presented on the day – a first for Pakistan – is the Suhaila, a sub-genre of the qawwali, which focuses on a virgin girl awaiting her wedding day. It is performed during the wedding ritual of manjhaan or mayoon when a bride divests herself from all beautification, wears pale yellow, and stays indoors to prepare for the big day. Suhaila is used, inter alia, to ward off evil spirits, teach the girl how to manage her married life and celebrate the upcoming nuptials. In the selected Suhaila titled ‘Toona’, the bride describes the spell she is going to cast on her future husband to make sure he never strays. The entire rendition was touching and beautifully expressed; definitely a treat for connoisseurs and laymen alike.

“What I find most charming about Ghayoor Moiz Mustafa Qawwalis there adherence to the original form of Khusravi qawwali and their loyalty to tradition,” says Ally. “In the future, I see them taking over the position of their fathers – Farid Ayaz and Abu Muhammad Qawwal, who are currently the greatest qawwals in the world. They may not yet have the knowledge of Sufism, religion, philosophy, politics and science of their elders, especially Fareed Ayaz Qawwal, but that being said, their music is phenomenal.”

A vital aspect of the presentation was the segue into the aadabs of a Mehfil-e-Samaa – the etiquette of being present at a qawwali gathering. From explaining the conditions required of transcendental ecstasy or haal; to the proper form of presenting nazrana or money to the qawwals; to the ritual of Rang – written by Hazrat Amir Khusrau and always presented at the end of a Mehfil-e-Samaa – this to-do list was a useful key to appreciating qawwali correctly. “Rang,” explains Ally, “is believed to have the power to result in the corporeal manifestations of saints, prophets, and loved ones for those who are spiritually enlightened and engaged.” “Thus,” he continues, “Qawalli, in essence, integrates spiritual, philosophical, religious, musical and poetic elements to create a vehicle to facilitate a spiritual connection between each participant of the Mehfil-e-Samaa and his beloved. ”This definitely corroborates the fact that qawalli is, therefore, always about love.

In conclusion, Ally Adnan’s talk was an important reminder that we are jointly responsible for preserving our cultural traditions and unless there is constant and consistent information gathering, sharing, record and critique, just the superficial enjoyment of a cultural legacy will not be enough to preserve this treasure in its proper historical and evolutionary form.

Qawwali - Chap Tilak Sab Cheen Li Re Mose Nainan Milayi Ke from Ally Adnan on Vimeo.

QUICK QUESTIONS WITH ALLY ADNAN

What sparked your interest in classical music?

Percussion was my first love when I was very young and most of my toys were drums, dholaks, tablas and other percussion instruments. My mother tells me I used to rock my head in perfect tempo when Noor Jehan’s songs were being played at home, even when I was just four months old!

Who inspired or guided you in the direction of sub-continental classical music?

I think the pleasure that listening to good music afforded me was the real inspiration. I was also in awe of the music and talent of UstadSalamat Ali Khan, UstadFateh Ali Khan, UstadShaukatHussain Khan, Roshanara Begum, IqbalBano and, more than anyone else, Noor Jehan. These people were more than capable musicians, they actually understood what music was all about and where it fit in the larger order of things – they were also wonderful and generous human beings. Ayub Romani and M. A. Sheikh, both from Radio Pakistan, also taught me a great deal about music, culture and love.

Do you have any formal training in music appreciation or in any other aspect of music? Do you play a classical instrument?

For a few years, I learnt how to play the tabla.While I believe I have good theoretical knowledge of the tabla,in practice, I’m a very poor tabla player andhaven’t played for almost 30 years. My goal to learn thetabla, formally, was to understand the instrument and our classical music and not to become a practicing musician. My teachers knew that and focussed more on theory than on practice.

Tell me something about your collection of classical music?

I have about 200,000 hours of music recordings from Pakistan and India. The vast majority of these are private live recordings. Some of the items are very rare, for example: Noor Jehan singing live for Shiv Kumar Sharma, PanditHariprasadChaurasia, UstanZakirHussain, etc.; UstadSalamat Ali Khan singing for the nautch girl Mizlaon whom he had a crush; Mehdi Hassan singing the songs of LataMangeshkar; AbidaParveen learning from UstadSalamat Ali Khan; Mehdi Hassan, UstadSalamat Ali Khan, and TufailNiazi singing together; Noor Jehan and NusratFateh Ali Khan singing the raagAhirBhairav together; and Noor Jehan singing the khayal and thumri.I have digitized 80,000 hours of this music and donated it to the National College of Arts, Lahore (NCA). I also give recordings to anyone who asks and have never held back any recording.

What are your areas of research with reference to classical music?

I am currently researching Qawwali, Islamic songs, the music of Baijis, Amir Khusrao, the ghazal, lost genres of music and raags.

What work have you planned in the future regarding your interest in classical music and qawwali?

I would really like to video tape interviews of major musicians, catalogue my collection and put it on the internet, deliver talks on music and qawwali all over the world, and learn and teach.

What do you find lacking in an average Pakistani's knowledge of classical music?

Other than the practitioners of music, very, very few people in Pakistan have a deep knowledge of classical music. In some cases, even that is patchy; and those who do know this field,use it to assert their cultural and intellectual superiority. They make simple things appear complex.

How should the interest in this genre be propagated?

There are several ways to do this; we must include music in our school curriculums; search for people, either in Pakistan or elsewhere, who know music and are both willing and able to share knowledge; televise programmes on classical music alone and not just fusion; and use good classical music in films and on television – Ho Mann Jahan, which had excellent music, is a great example.. And importantly, we must deplore the act of being miserly with knowledge as a society and shame those who are territorial about the little knowledge they have and make things appear unnecessarily complex to appear knowledgeable themselves. Music is not, has never been, and does not need to be esoteric. We need to expose these so-called musicologists for the charlatans that they are!

What is the most optimistic thing you have seen in the classical music scene in Pakistan recently?

I would say the amount of activity – I have never seen this ever before. We romanticize the past, but never in the past has there been as much cultural activity as there is now –in one evening in Karachi I attended a dastangoi mehfil and qawwali, was invited to a kathak performance, a stage musical (Grease), and a stand-up comedy event. I am also very happy that classical musicians are finally able to make a good living in Pakistan. They are no longer destitute and do well nowadays.

*Photographs by Hashim Pervaiz