Francis Wade

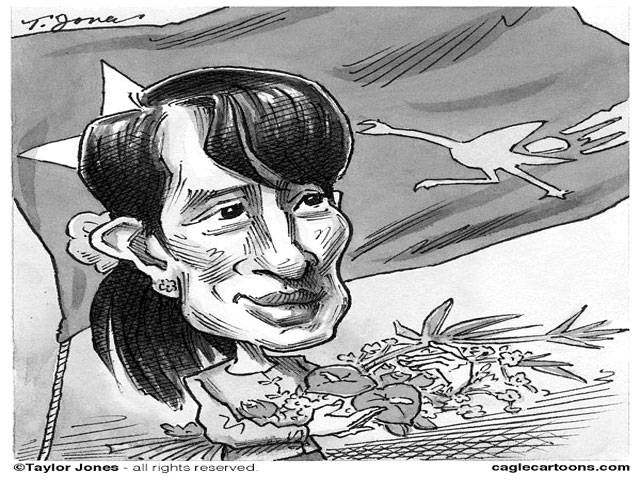

Flanked by parched paddy fields, the route leading south out of Yangon’s busy centre and towards the rural township of Kawhmu now holds an altogether new significance. Along this pot-holed thoroughfare, a cavalcade of trucks last Saturday parted a sea of people and offered passage for Aung San Suu Kyi to reach her constituency. There she spent the night, before rising the next day to look out over a dusty landscape that has become the victory ground of Myanmar’s pro-democracy movement.

The decision to make her maiden entrance to parliament via the gates of Kawhmu comes as little surprise. Although only two hours from the centre of Myanmar’s economic hub, its inhabitants have been far removed from the frenzy of international excitement that marked the build-up to Sunday’s vote; neither will they feel the expected financial benefits - the booming tourism industry and development capital - that’ll follow this first step towards democratic transition, at least for the time being.

But Suu Kyi will seek to become a bridgehead between these people and the epicentre of Myanmar’s development, her proverbial reach connecting two ends of a 30 kilometre stretch of cracked tarmac that has become the physical embodiment of Myanmar’s road to democracy. Their remove is plain to see: Su Su Nway, a prominent labour rights activist and former political prisoner who was in the district on Saturday to drum up support for the opposition, said that despite its proximity to Yangon, this area had suffered under “extreme poverty”.

“Most people here are farmers. Their farmland was confiscated [by the authorities] and they do not have any ownership rights. University graduates are unemployed and a lot of people who live in remote areas are very poor.”

Nobel laureate Suu Kyi, who weathered illness and intimidation as she canvassed across Myanmar, faces a raft of challenges far more complex and daunting than one could imagine, right from the micro-level battles for development and infrastructure in Kawhmu, to carrying upon her shoulders the burdens and aspirations of the country’s entire populace. And she will be impeded wherever the political elite feels she is gaining too much ground.

Scattered among the hundreds of supporters that lined the road, as her convoy rolled in to Kawhmu on Saturday, were government spooks brazenly filming the hordes of foreign journalists documenting her journey, a signal that real unease remains, despite recent progress to a more open society.

Battle on two fronts

She is careful to emphasise that her campaign has fought a battle on two fronts: accompanying the bid for parliamentary seats, the National League for Democracy (NLD) has also sought to galvanise political awareness among Myanma that for decades have been sidelined from the country’s decision-making arena. Kawhmu thus becomes the staging ground for a broader push by the opposition to bring peripheral populations to the table, and already this seemingly insignificant region has been placed firmly on the world’s map.

That pattern, she hopes, will ripple out across the country. Thousands turned out to her rallies in the border regions, where the normally revered icon has struggled to cast herself as a legitimate figurehead for ethnic minority groups, a sign she judges as a marker of how successful her quest to go beyond just parliament has been.

By Sunday evening, the streets around the NLD’s headquarters in Yangon were choked with traffic, as revellers made their way to watch results trickle in. The thousands gathered outside erupted in cheers as seats fell to the NLD across the country. Even in the army stronghold of Naypyidaw, where the government has spent the past six years encamped in gleaming compounds far removed from the day to day lives of ordinary Myanmar, ruling Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) candidates could not outmuscle the opposition. But behind the rich symbolism of Sunday’s celebrations, doubts linger over how significant a shift this is in Myanmar’s political landscape. Suu Kyi’s party will occupy fewer than five per cent of seats, and, as yet, she and her colleagues have struggled to map out how they will utilise their limited clout in parliament over the coming years.

The seeming lack of clarity over political strategy has been smothered by the celebrations of recent days and even the progressive rhetoric from the government. During a press conference at her lakeside compound last week, prior to the vote, Suu Kyi was asked what her first priority upon entering parliament would be: her light-hearted answer, that she must first work up the strength to visit Naypyidaw, drew laughter from the crowd, but reinforced a sense that they were still uncertain of how to fit in to a parliament where they will not be altogether welcome.

With the victory now behind them, that will become the NLD’s key test over the coming months. Unconditional reverence among Myanma is the wave on which they will ride into parliament, but political longevity requires results. Given the decades spent fighting for this moment, there will be a patience and acceptance that the country’s malaise cannot be cured overnight, but Suu Kyi must begin to articulate a roadmap for the future that addresses the pitfalls bound to accompany Myanmar’s transition. Back in Kawhmu, the almost deified admiration she and the National League for Democracy command contrasts sharply with that of the Union Solidarity and Development Party, whose candidates on Saturday remained, dour faced, inside their trucks, snubbing approaches from journalists and largely bereft of visible support. Few stuck around to watch them; instead inhabitants flocked to a spot along that pockmarked road from Yangon that in the coming years will grow poignantly familiar to Suu Kyi, and whose onerous terrain will be a test of her ability to navigate Myanmar’s uncertain political landscape. –Aljazeera

Thursday, April 18, 2024

Myanmar’s pockmarked road to democracy

'That'll be awesome,' Rohit Sharma on idea of Pakistan vs India Test series

9:17 PM | April 18, 2024

Stefanos Tsitsipas advances in Barcelona

4:19 PM | April 18, 2024

Australia's Law named head coach of T20 World Cup hosts USA

4:18 PM | April 18, 2024

Azam Khan likely to miss today's match with knee problem

4:17 PM | April 18, 2024

Challenge Cup 2023 final stage likely to be played in Jinnah Stadium: Sources

4:16 PM | April 18, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Wheat War

April 18, 2024

Rail Revival

April 17, 2024

Addressing Climate Change

April 17, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

Tax tangle

April 18, 2024

Workforce inequality

April 17, 2024

New partnerships

April 17, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024