David Rohde

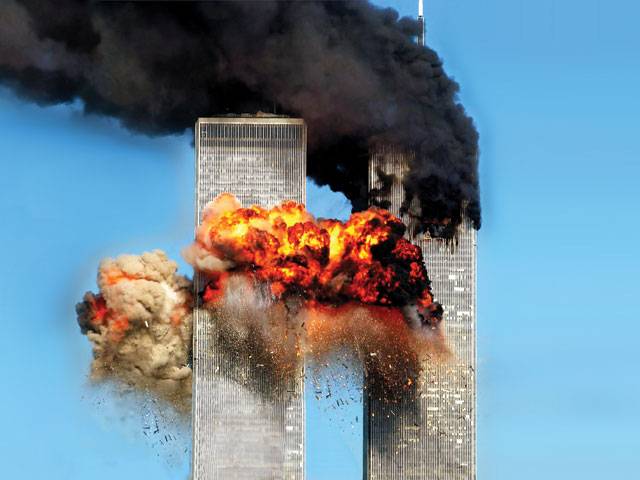

NEW YORK - In August 2013, one of five men accused of helping carry out the September 2001 terrorist attacks met with his defense lawyers in the U.S. detention center in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Ramzi bin al Shibh, who military prosecutors say relayed money and messages to the 9/11 hijackers, asked his lawyers to send a message to his nephew in Yemen. After the meeting, the defense team’s translator went to another part of the U.S. Navy base, called Yemen from a landline and had a five-minute phone conversation with Bin al Shibh’s brother.

Defense lawyers say the translator conveyed an innocuous message from Bin al Shibh in which he urged his nephew to study hard in school. But two years on, that five-minute phone call, which has not been previously reported, continues to hinder the course of justice in the military commissions set up to prosecute people held at Guantanamo Bay as enemy combatants in the U.S. war on terror.

When they learned of the call in April 2014, U.S. officials feared that Bin al Shibh might have conveyed a coded message to al Qaeda operatives in Yemen. The Federal Bureau of Investigation launched a botched effort to turn a member of Bin al Shibh’s defense team into a confidential informant. Outraged defense lawyers then waged legal war on the FBI and military prosecutors, halting the trial of all five 9/11 defendants. The trial has yet to resume.

Experts said the call and the legal trench warfare it sparked is the latest example of how President Barack Obama’s effort to reform Guantanamo’s military commissions - by appointing experienced death penalty defense lawyers and other legal changes - has failed. “By any measure, the commissions have been a failure,” said David Cole, a Georgetown University law professor. “They’ve obtained almost no convictions other than a handful of guilty pleas, and many of the convictions have been overturned on appeal.”

Nine years after President George W. Bush created the commissions and six years after Obama reformed them, only eight defendants have been fully prosecuted. Three verdicts have been overturned. Most of the 36 detainees whom the Obama administration said it would prosecute have not been charged. Fourteen years after the crime, the trial of the 9/11 defendants remains years away.

The death penalty defense lawyers appointed as part of Obama’s reforms have blanketed military judges with pre-trial motions that challenge nearly every aspect of the 9/11 trial. A former defense team member who asked not to be identified called the proceedings a “fiasco.”

U.S. Army General Mark Martins, a Harvard Law School graduate who was named chief prosecutor of the military commissions in 2011, defended the pace of the trials. In an interview and in public speeches, he argued that the military commissions are fair, lawful and protect the American public. “It’s a struggle,” said one official, who asked not to be identified. “If you look at the history and where we are today, obviously it’s a challenge.”

BREACH OR NO BREACH?

The call to Yemen immediately sparked division in the Bin al Shibh defense team, according to two people familiar with the matter. “We don’t know what type of code could have been in the ,” said one of the people with knowledge of the matter. “We don’t know if he could have revealed some important information through it.” Before the 2001 attacks, Bin al Shibh, a native of Yemen, shared an apartment in Hamburg, Germany, with hijacker Mohammad Atta and applied to receive flight training in the United States. After repeatedly being denied a U.S. visa, Bin al Shibh allegedly wired funds to plotters already inside the United States.

After he was captured in Pakistan in 2002, Bin al Shibh was held for four years at a U.S. Central Intelligence Agency detention center, or “black site,” before being moved to Guantanamo Bay. In 2008, military prosecutors charged Bin al Shibh with hijacking, terrorism and mass murder for his alleged role in the 9/11 attacks.

Under international law, military tribunals can try defendants only for war crimes. “Conspiracy to blow up an airliner is a criminal offense,” not a war crime, Freedman said. The 9/11 trial, in particular, has caused problems because each defendant faces the death penalty. The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that one of the most basic rights of capital defendants is the ability to cite mitigating factors before they are sentenced to death, Nevin said. “If there has to be this much secrecy, if there has to be this many restrictions on a lawyer’s ability to provide a defense,” Nevin said, “then you just can’t have a capital prosecution.”

Members of the Bin al Shibh defense team feared that if the call was a security breach, even an inadvertent one, they could be prosecuted for violating post-9/11 national security laws. New York defense lawyer Lynne Stewart was sentenced to 10 years in prison after a federal jury convicted her in 2005 of passing messages from a radical Egyptian cleric to his followers.

Members of the defense team asked the team’s chief lawyer, James Harrington, to report the call to Yemen to military officials, according to two people familiar with the matter. Harrington declined to do so because he did not believe that it violated security protocols. In an interview, Harrington said the call was a routine personal statement from Bin al Shibh to his family. He also said that gaining the trust of Bin al Shibh and his family was his duty as a death penalty defense lawyer. “There was no effort to conceal anything that we did,” A Defense Department spokesman said: “All detainees have the ability to communicate with their families.” He declined to say whether lawyers can relay messages to their clients’ families. “If defense lawyers are contacting their clients’ families, they will be able to provide you those details,” he said.

And they have accused military officials of placing listening devices in rooms where they meet their clients. The government’s obsession with secrecy, they contend, is driven by the CIA’s desire to conceal from the public the extent to which it tortured detainees. “It’s not clear what all the rules are,” said Nevin. “The government refuses to give us classification guidance.”

A VISIT FROM THE FBI

At the time of the Bin al Shibh translator’s call to Yemen, the team had no security officer, according to the two people familiar with the matter. The team’s security officer had moved to another position, and a replacement had not been found. In a combative court hearing at Guantanamo, Harrington called for an investigation of the FBI and accused the agency of trying to turn the member of Bin al Shibh’s defense team into a confidential informant.

“To say this is a chilling experience for all of us is a gross understatement,” Harrington told Col. James Pohl, the military judge who is overseeing the trial of the 9/11 defendants. Pohl then ordered all U.S. government agencies to disclose any efforts to turn members of 9/11 defense teams into confidential informants.

“Mr Bin al Shibh wanted a letter sent to his brother in Yemen which encouraged his brother’s son, who was starting in a new school for him, to study hard,” Harrington said in an email. “In a telephone call with the brother about the entire family, our interpreter told him that Ramzi wished his son well in his school.” Harrington said he had instructed the translator to make the call.

In February 2015, nearly a year after the FBI agents visited the house of the Bin al Shibh defense team member, Judge Pohl, the five defendants and their legal teams gathered in Guantanamo to resume pre-trial hearings. The hearing abruptly ended when several 9/11 defendants said the new translator assigned to Bin al Shibh’s defense team, who was also a military contractor, had worked on a CIA black site where they were held captive.

Defense lawyers requested that all 130 military personnel and civilians working for the defense teams be investigated for secret ties to the U.S. government. Military prosecutors denied any wrongdoing and blamed defense lawyers for failing to investigate the background of the translator.

The military judge, Col. Pohl, canceled the pre-trial hearings and ordered that the Bin al Shibh team be given yet another translator. As for what was actually said during the five-minute call to Yemen, a government official who spoke on condition of anonymity said the conversation appears to have been innocuous. “It turned out to be much ado about nothing,” he said.–Reuters

Friday, April 19, 2024

How a 5-minute phone call put 9/11 trial on hold for more than a year

8:27 AM | April 19, 2024

8:09 AM | April 19, 2024

President, PM condemn suicide blast, firing in Karachi

2:24 PM | April 19, 2024

Fly Jinnah launches another international route

2:23 PM | April 19, 2024

Interior minister directs foolproof security for Chinese nationals

2:20 PM | April 19, 2024

UNICEF to provide $20m for youth projects in Pakistan

2:04 PM | April 19, 2024

Maryam reviews progress on Nawaz Sharif IT City project in Lahore

2:04 PM | April 19, 2024

A Tense Neighbourhood

April 19, 2024

Dubai Underwater

April 19, 2024

X Debate Continues

April 19, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Kite tragedy

April 19, 2024

Discipline dilemma

April 19, 2024

Urgent plea

April 19, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024