Ahmed E Souaiaia

Most Western governments and some observers argue that the elections that took place in Syria on June 3 were not legitimate because not all Syrians were able (or willing) to participate, they were held under war conditions, and Syrians were coerced into voting for the current president. These would be reasonable arguments if they were consistently applied. A brief examination of similar cases and relevant facts reveals that this is not the case.

First, US administrations have overseen numerous elections and produced national constitutions under war conditions and in the middle of sectarian strife in Afghanistan and Iraq. Administration officials have often argued that even under these circumstances, elections and referendums are necessary to instil democratic tradition, isolate extremists, and legitimize governments. Are these functions of democracy not applicable in Syria?

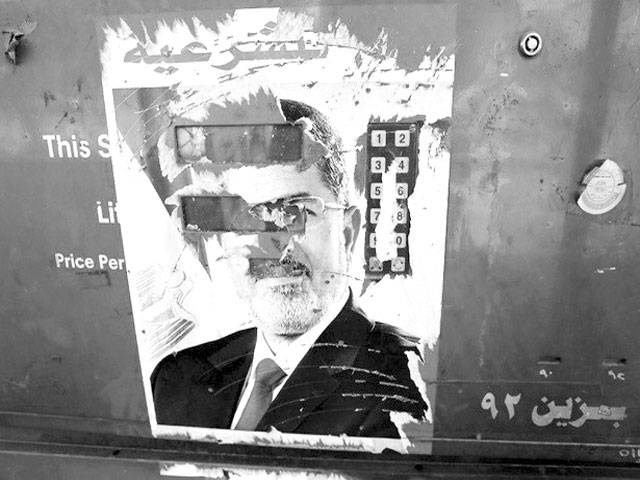

Second, 56% of Egyptian voters did not take part in the recent elections that endorsed former military chief Abdul Fattah al-Sisi. Moreover, al-Sisi came to power after overthrowing a president who was legitimately elected by higher voter participation and who faced stronger challengers.

Yet the US administration, the rulers of Saudi Arabia, and many Western governments readily embraced al-Sisi despite his weak mandate, the extraordinary events that preceded the elections, and the harsh measures (introduced under his watch) that stifled dissent and criminalized journalists and members of the opposition.

Third, contending that Syrians voted the way they did because they were fearful and coerced is an insult to all Syrians, both those who voted and those who did not vote. Such a contention depicts them as cowards, incapable of making proper decisions without outside help. Syrians, who have been living under extreme conditions for more than three years now, could have chosen to stay at home (as some did) instead of risking their lives to put a dot of ink on a piece of paper.

After all, most Syrians knew that Bashar al-Assad would win and that the West would not recognize the results. But many Syrians, for a myriad of reasons, wanted to vote for al-Assad. It is important to remember that earlier studies commissioned by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and other Western entities predicted that Assad would win by about 60%, which explains why elections were not part of any political solution supported by the Western governments. Instead, they favoured a negotiated power transfer to an opposition coalition that represents less than 4% of the population.

There are many reasons why Syrians enthusiastically thronged polling stations inside and outside Syria to vote for al-Assad, some literally with their own blood instead of ink. With instability, civil wars, and weak governments resulting from short-sighted Western meddling, it is understandable that many people in the Middle East prefer to spite the US and its rich Arab allies by voting for the person most disliked by the West.

Instead of considering the actual facts and motives, US administration officials, the French government, and rulers of some of the Gulf States continue to ignore the will and welfare of the Syrian people without providing credible alternatives. They claim that Bashar al-Assad is out of touch and has lost legitimacy. Let’s consider some specifics.

On the same day the Syrian government announced the results of the presidential elections in which 88% of Syrian voters, with 73% turnout, elected Bashar al-Assad, US Secretary of State John Kerry arrived in Lebanon. Speaking in Beirut, he declared that “the elections [in Syria] are non-elections. A great big zero ... Nothing has changed between the day before the election and after.”

Ironically for someone who described President Assad as out of touch with reality, Kerry was speaking in a country that has had no president for two weeks now (a situation that may persist for months), was without any government for more than 10 months, and whose lawmakers decided to give themselves a 16-month extension of their term (presumably it will now end in November 2014).

That wilful cognitive dissonance is symptomatic of Western governments’ utter failure to present a credible alternative even as they criticize the governments and governmental processes of countries they do not like. Moreover, the countries they are propping up as acceptable models are not even functional, let alone democratic and stable.

First, Iraq, which just held its first post-US occupation legislative elections, continues to struggle with security, economic, and political challenges. Because of the strange power-sharing arrangement introduced under the watch of Western occupation forces, Iraq has a parliament deeply divided along sectarian, ethnic, and ideological lines, making it difficult to form a strong and stable government in the near future.

Second, Libya, “freed” from Muammar Gaddafi’s grip three years ago by an alliance between Qatar (which financed and armed rebel groups) and NATO (which provided the air power) is facing its own civil war, pitting secular military generals against armed groups, some of whom are affiliated with al-Qaeda. Moreover, instability and availability of all kinds of weapons in the hands of all kinds of armed groups are threatening the stability of neighbouring countries like Tunisia, Egypt, and Algeria-three countries with fragile governments and strong presence of al-Qaeda affiliates.

Third, other Arab allies of the US are exemplars of tyranny and authoritarianism, not responsible governance. These allies include countries like Bahrain which continues to abuse peaceful protesters, Saudi Arabia which criminalizes dissent and jails human rights activists, and Qatar which imprisons poets and abuses foreign labourers and immigrants. None of these countries have held elections-farcical or otherwise.

Historically, the US administration and its main regional ally, Saudi Arabia, have promoted custom-made, top-down controlled models of governance where they balance power by rewarding warlords and ethnic and religious factions with tools that paralyze governments instead of making them functional.

The 1989 Ta’if Agreement, which changed the power-sharing formula in Lebanon, and the constitution of Iraq, inked under the watch of US forces, are good examples of tightly tailored political tools that cannot allow for the emergence of governments empowered by the people. Instead, these tools produce regimes that are dependent on regional or international backers.

All this ultimately shows that US foreign policymakers are willing to support anti-democratic and ultimately unstable governments instead of investing in, and accepting the consequences of, participatory democracies. Though the US may not like the short-term outcomes of developing democratic processes, it is in everyone’s long-term interest to stop purposefully undermining-whether by intentionally booby-trapping or by rejecting the legitimacy of-those political processes.

Professor Ahmed E Souaiaia teaches at the University of Iowa.–Asia Times Online

Friday, April 19, 2024

US hypocrisy and Middle East democracy

Caption: US hypocrisy and Middle East democracy

8:27 AM | April 19, 2024

8:09 AM | April 19, 2024

Iconic actor Muhammad Ali being remembered on birth anniversary

10:02 PM | April 19, 2024

Death anniversary of Urdu writer Imtiaz Ali Taj today

10:01 PM | April 19, 2024

Umer Sharif remembered on birth anniversary

10:00 PM | April 19, 2024

Islamabad High Court to monitor Hajj 2024 operations

9:58 PM | April 19, 2024

Pak economy improving, funds will be provided on request: IMF

9:57 PM | April 19, 2024

A Tense Neighbourhood

April 19, 2024

Dubai Underwater

April 19, 2024

X Debate Continues

April 19, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Kite tragedy

April 19, 2024

Discipline dilemma

April 19, 2024

Urgent plea

April 19, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024