John Kemp

Central Oklahoma faces a significantly increased risk of a damaging earthquake, and the threat is probably related to oil and gas extraction, the US Geological Survey warned on Monday last.

‘As a result of the increased number of small and moderate shocks, the likelihood of future, damaging earthquakes has increased for central and north-central Oklahoma,’ USGS said.

More than 180 earthquakes of magnitude 3.0 or greater were recorded in Oklahoma between October 2013 and the middle of April 2014, compared with a long-term average of just two per year between 1978 and 2008. The risk of a more damaging earthquake of magnitude 5.5 or greater has increased significantly, USGS warned.

‘Building owners and government officials should have a special concern for older, unreinforced brick structures, which are vulnerable to serious damage during sufficient shaking.’ Oklahoma has long been known as an earthquake zone, but the recent increase does not appear to be due to typical random fluctuations in natural seismicity, according to USGS.

Instead, USGS experts believe a contributing factor has been the disposal of waste water from oil and gas production by injecting it into deep underground formations. Scientists have long known the injection or withdrawal of large volumes of fluid into or from an underground rock formation can trigger earthquakes by changing stress along existing fault lines and lubricating them.

Small and medium-sized earthquakes have been triggered by mining, oil and gas extraction, geothermal energy, enhanced oil recovery, carbon capture and storage and hydroelectric dams. In the 1960s, the underground disposal of waste fluids from the US Army’s chemical weapons facility at Denver, Colorado triggered more than 1,500 earthquakes, including three registering more than magnitude 5.0.

Water injection at Geysers geothermal power plant in northern California has caused a large number of small tremors, and the power plant has a well established programme for compensating local residents for minor damage to their property. The magnitude of the earthquake is related to the surface area that ruptures, which in turn is related to the volume of fluid injected or withdrawn from the underground rock formation. So in general, larger fluid injections are capable of causing larger earthquakes.

The amount of waste water injected in a typical disposal well is not normally large enough to trigger a significant earthquake. But USGS has begun to worry that a series of small quakes could lead to a larger one. In November 2011, a magnitude 5.0 earthquake occurred in close proximity to active fluid injection wells near the town of Prague in Oklahoma. Less than a day later, a magnitude 5.7 earthquake was reported, with at least one magnitude 5.0 aftershock.

USGS geologists said the initial magnitude 5.0 quake ‘may have promoted failure of the main shock and thousands of aftershocks along the Wilzetta fault’. Before the Prague quake, the strongest tremor on record in Oklahoma reached magnitude 5.5 and occurred in 1952.

CALMING CONCERNS

The increasing number of earthquakes related to oil and gas extraction is bound to heighten concern about the safety of fracking, which in turn will intensify scrutiny of the industry. But there are several important points to bear in mind.

First, the earthquakes are not related to hydraulic fracturing but to disposal of contaminated waste water, which is linked to all oil and gas extraction activities, not just fracking. All oil and gas extraction produces large amounts of waste water, which is normally reinjected underground.

Second, fluid injection is not restricted to oil and gas production. Geothermal, carbon capture and storage and a range of other human activities all pose a heightened risk of earthquakes. Carbon capture and storage would probably pose the biggest potential danger because of the volume involved. Third, the risk of induced seismicity seems to be concentrated in heavily faulted areas that are already under high levels of natural stress. Fluid injection in areas already known to be prone to earthquakes poses the greatest risk.

For safety reasons, it is vital that would-be drillers understand the local geology: injecting waste water near California’s San Andreas fault would clearly not be a good idea. The increasing number of small earthquakes reported in Oklahoma, Arkansas, Ohio, Texas and Colorado stems from the general increase in oil and gas production in the United States from conventional and shale deposits, all of which produce large volumes of waste water. As evidence mounts that the US oil and gas boom is contributing to an increase in the number of earthquakes, energy producers must get ready for another round of tough questions about safety. If USGS is correct, it is only a matter of time before an earthquake occurs that is strong enough to inflict noticeable damage and is traced back to oil and gas production.

The risks cannot be eliminated entirely, but they can be managed. It is important for the industry to take steps ahead of time, including paying greater attention to local fault risks before drilling, so it can demonstrate all reasonable precautions were taken.

–John Kemp is a Reuters market analyst. The views expressed are his own.

Friday, April 19, 2024

Oklahoma earthquakes linked to oil and gas production

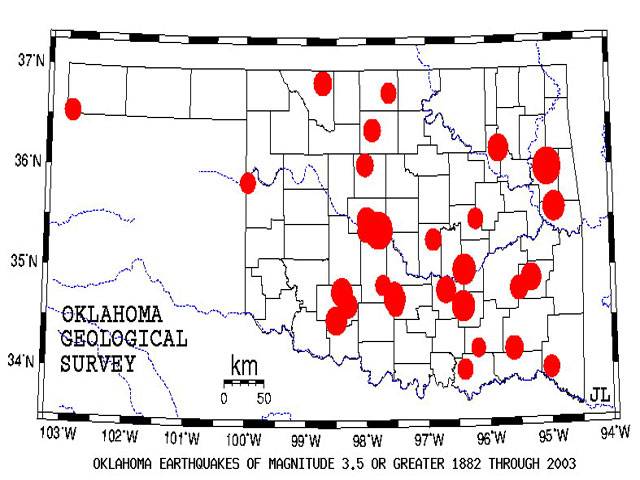

Caption: Oklahoma earthquakes linked to oil and gas production

President calls for meaningful dialogue to end polarisation

April 19, 2024

KP minister briefed on issues about sales tax on services

April 19, 2024

64th anniversary of freedom fighter Mirzali Khan marked

April 19, 2024

893,000 students appear in SSC exams in KP

April 19, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Wheat War

April 18, 2024

Rail Revival

April 17, 2024

Addressing Climate Change

April 17, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

Tax tangle

April 18, 2024

Workforce inequality

April 17, 2024

New partnerships

April 17, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024