David Ignatius

Americans are clamouring to speed up the 2014 security transition in Afghanistan so that US troops can come home sooner. But the buzz in Kabul is about the political transition to a post-Karzai government - and whether that handover should be accelerated.

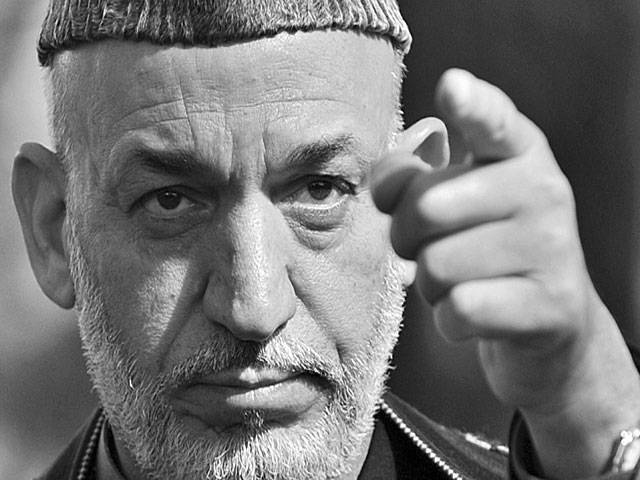

Under the Afghan constitution, a presidential election must take place before the end of 2014 to choose a successor to President Hamid Karzai, who won a second term in 2009. But there’s growing talk about moving up the election to 2013, when more Nato troops will be there to provide security.

“There are perfectly good arguments why 2013 would be a good time” for the presidential election, William Patey, Britain’s ambassador in Kabul, said in an interview with the Guardian newspaper last week. He added that the British “wouldn’t have any objections.” Afghanistan’s independent election commission would have to approve any change.

One argument for an earlier election is that it would focus attention on the political transition ahead - rather than on just the military situation. An emphasis on military issues at the expense of politics and governance has plagued the US effort in Afghanistan since the beginning.

“We have a very detailed and micromanaged security transition plan, but we don’t really have any functional plan for the transfer of political power,” complains one adviser to the Nato mission in Kabul.

The Obama administration is assuming the election will take place as scheduled in 2014. But regardless of the polling date, some top US officials agree it’s time to focus more on politics and a bit less on the military handover that gets the headlines. Already, Ryan Crocker, the veteran US ambassador in Kabul, is expanding his outreach to Afghan politicians in the hope of encouraging a new generation of leaders, post-Karzai.

I don’t know where this sort of political outreach fits in the toolbox of US power. Some would argue that it should be a CIA function, since it may involve covert contacts and money. But why not do this political work openly, through the embassy? It seems crazy to have spent hundreds of billions of dollars trying to stabilize Afghanistan, and then pretend Washington isn’t interested in shaping the political landscape and encouraging a strong and popular successor to Karzai.

A US focus on Afghan politics might confound the Taliban. Right now, the insurgents seem to think that if they can outlast the planned withdrawal of Nato combat troops, who will give up their lead role in mid-2013, then they’re home free. The Taliban might be less sanguine, and more eager to bargain, if they saw the United States encouraging new political leaders.

“There is little doubt in my mind that the US government needs to make an effort to support key moderate leaders in each of the groups,” argues one prominent Afghan business leader. A deal with the Taliban before there’s a new Afghan government “will end in tears,” he warns.

Here are some of the political prospects mentioned by US, European and Afghan analysts: Farooq Wardak, a Pashtun who is education minister; Hanif Atmar, a Pashtun former interior minister; Ashraf Ghani, a Pashtun former finance minister who is now helping manage transition efforts; Amrullah Saleh, a Tajik former intelligence chief; Atta Mohammad Noor, the popular Tajik governor of Balkh province; Shukria Barakzai, a Pashtun member of parliament who speaks out on women’s issues; and Razaman Bashardost, a Hazara former planning minister who campaigns against corruption.

Any of these Afghan politicians (and there are a dozen more I could have mentioned) would give the country a more dynamic political face - less corrupt and more competent than the mercurial Karzai has proved to be. “We need a new political dynamic that is stable and aligned with our security interests,” stresses the Nato adviser.

With an election ahead to decide Afghanistan’s political future, why is the US government trying so hard to negotiate a deal now with the Taliban? That’s a good question. Perhaps the Obama administration simply started the process of outreach to the enemy a year too soon, before a new leadership team was forming in Kabul.

The deadlocked negotiations with the Taliban are another reason to focus more on politics - so that a more popular and less tainted Afghan government could bargain over the country’s future with an enemy that, however potent its roadside bombs, is widely disliked.

“Karzai’s departure may very well allow us to press the ‘reset’ button,” says the Afghan businessman. The sooner the better.

–Washington Post

Saturday, April 20, 2024

In Afghanistan, who follows Hamid Karzai?

8:27 AM | April 19, 2024

8:09 AM | April 19, 2024

Pak economy improving, funds will be provided on request: IMF

9:57 PM | April 19, 2024

Minister advocates for IT growth with public-private collaboration

9:57 PM | April 19, 2024

Judges' letter: IHC seeks suggestions from all judges

9:55 PM | April 19, 2024

Formula 1 returns to China for Round 5

9:05 PM | April 19, 2024

Germany head coach Julian Nagelsmann extends contract till 2026 World Cup

9:00 PM | April 19, 2024

A Tense Neighbourhood

April 19, 2024

Dubai Underwater

April 19, 2024

X Debate Continues

April 19, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Kite tragedy

April 19, 2024

Discipline dilemma

April 19, 2024

Urgent plea

April 19, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024