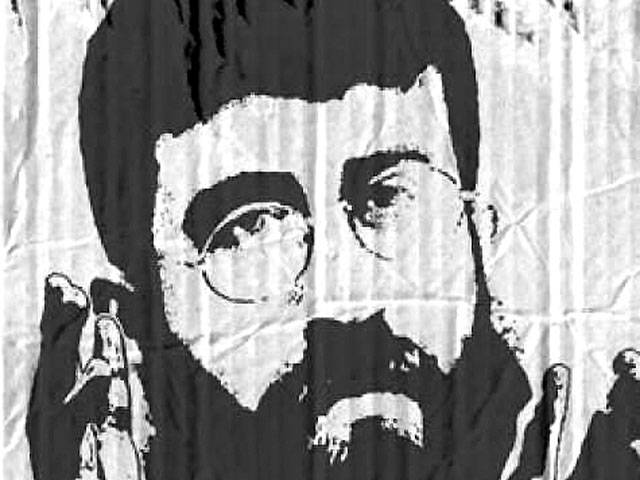

FAWAZ TURKI

Consider the case of Khader Adnan, a Palestinian political prisoner held in jail by the Zionist occupation authorities without charge and without any semblance of due process since mid-December.

Adnan, 33, had gone on a hunger strike for 11 weeks to protest his incarceration and that of thousands of other political prisoners. He lost a third of his weight and, according to officials from Physicians for Human Rights who visited him, reportedly while shackled to a bed in his cell, “suffered significant muscular atrophy”. He was said to be at “immediate risk of death”. When authorities arrest and hold a man on flimsy charges, even trumped-up charges, that is considered, in jurisprudence, problematic enough, but at least the accused in this case will have his day in court to rebut those charges, ideally with a skilled lawyer at hand.

But when you arrest and hold a man, keeping him incarcerated indefinitely, with no charges brought against him and no prospect of a trial, you are harking back to a judicial system plucked from the Dark Ages. It is not a system characteristic of a society that grandiosely identifies itself as “the only democracy in the Middle East”.

No we’re not taking about Iraq under the brutal regime of Saddam Hussain or about Libya under the lunatic regime of Muammar Gaddafi. We’re talking about the racist regime (how else would you describe it?) of Zionist rulers, a regime whose courts continue to regard Palestinians, much in the manner that South Africa under apartheid had regarded black Africans, as a lower species of men and women to be judged by laws ‘apart’ from those that govern Israelis.

Adnan was held under a law called Administrative Detention — applied only to Palestinians, never to Israelis — that seeks indefinite imprisonment of a suspect without charges or trial.

The imprisonment is not imposed as punishment for a known crime the suspect has committed, but in order to prevent him from committing a crime, if that person is deemed, say by an arbitrary occupation functionary, likely to commit one. And so where is George Orwell when you need him?

In civilised society (read, a genuine democracy) no one can be arrested without being told the grounds for such an arrest. Once arrested, a citizen has well-defined rights that include the right of being informed of the criminal charge levelled against him, the right of being brought for a preliminary hearing before a magistrate within a specified period of time, and the right to be represented by a lawyer of his choice. But that applies to an open constitutional democracy.

Israel cannot be defined, by any stretch of the imagination, as one such entity, at least when seen in context of the apartheid laws it reserves for Palestinians. Many of the occupation laws in force in the West Bank, that govern the everyday life of Palestinians, are draconian, but none surely is more draconian than the infamous Administrative Detention Law, under which countless Palestinian prisoners have languished in Israeli prisons for years. Currently, as many as 309 are held without charge.

Not a word from the State Department about any of it — and this is a government department well-known for its much-trumpeted annual Human Rights Report detailing abuses, similar to Israel’s, by other countries. The 2010 report, for example, included a long section on the repressive detention practices of China, berating Beijing for a “lack of due process in judicial proceedings and the use of administrative detention”. Israel was not excoriated in the report for formalising exactly the same practices that the State Department was now condemning China for.

Alas, these practices, universally recognised as a defining attribute of despotism, have become normal in Israel, absorbed into the political culture as if by a process of osmosis. That is why the case of Adnan stirred little public debate in the Israeli press.

Irish reflection

Happily, a deal was reached on Tuesday when Adnan called off his fast in exchange for a formal promise by the Israeli authorities to release him on April 17. But had Adnan’s hunger strike resulted in his death, as seemed very likely earlier in the week, there would have been hell to pay. (In the West Bank and Gaza thousands had rallied to his cause.) At the very least, Israel would have had a Bobby Sands case on its hands.

When on March 1, 1981, Irish Republican prisoners, in a showdown with then British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, went on a hunger strike, 10 prisoners ended up starving themselves to death nine weeks later rather than give in. Bobby Sands became the most famous among the group after he was elected as a member of parliament during the strike, which prompted media interest around the world.

The strike, along with its tragic conclusion, radicalised the Republican movement and nationalist politics, and was the driving force that enabled the Sinn Fein to become a mainstream political party. Sands’s funeral alone attracted 100,000 mourners and he went on to become an iconic figure in Irish cultural lore. It is true, very true, that when a man dies his life ends, but when a patriot dies his life begins — its impact durable and pervasive.

It was a happy ending for Adnan, a baker by trade and a political activist by inclination. But what about those 309 prisoners who continue to languish behind bars without being charged or brought to trial?

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. – Gulf News

Friday, April 19, 2024

Adnan’s case highlights Israel’s racist legal system

Govt encouraging investments in ICT: Shaza

April 19, 2024

Appointed

April 19, 2024

Rashakai pSEZ to get Rs470.78m solar panels project

April 19, 2024

Decision to boost FED on cigarettes yields positive results

April 19, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Wheat War

April 18, 2024

Rail Revival

April 17, 2024

Addressing Climate Change

April 17, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

Tax tangle

April 18, 2024

Workforce inequality

April 17, 2024

New partnerships

April 17, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024