LONDON-Two skulls found in China shed light on the ancient humans who inhabited the region before our own species arrived. We know that Europe and western Asia was dominated by the Neanderthals before Homo sapiens displaced them.

But remains belonging to equivalent populations in East and Central Asia have been scarce.

It’s unclear if the finds are linked to the Denisovans, a mysterious human group known only from DNA analysis of a tooth and finger bone from Siberia.

Prof Erik Trinkaus, one of the authors of a study on the remains in Science journal, said it was not possible to say at this stage whether the ancient people from Xuchang were connected to the Denisovans.

“The issue here is the patterns of variation and the population dynamics of ‘archaic’ populations during the later part of the Pleistocene,” Prof Trinkaus, from Washington University in St Louis, told BBC News.

Modern humans (Homo sapiens) originated in Africa some 200,000 years ago before expanding out across Asia, Europe, Oceania and the Americas after 60,000 years ago. As they spread across the world, they displaced the existing populations they encountered, such as the Neanderthals and Denisovans - but some limited interbreeding occurred.

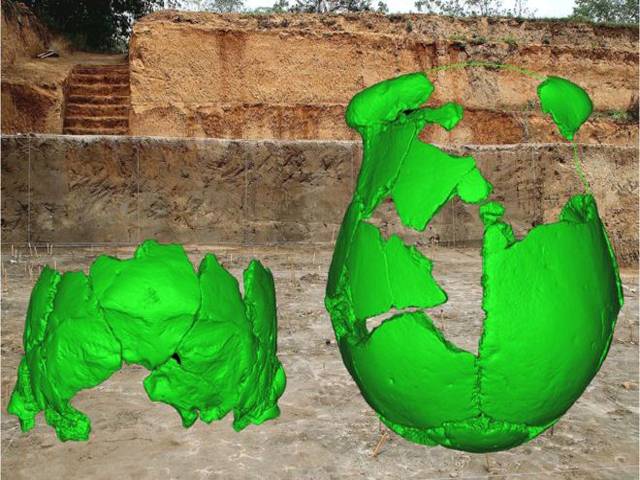

The partial skulls from China are between 105,000 and 125,000 years old and lack faces. But they show clear similarities to and differences from their Neanderthal contemporaries in the west.

“There’s a certain amount of regional diversity at this time, but also there are trends in basic biology that are shared by everybody. And the supposed Neanderthal characteristics show that all these populations were interconnected,” Prof Trinkaus explained.

Prof Trinkaus, Zhan-Yang Li, from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, and others found that the specimens show some characteristics, like a low, broad braincase, that link them to even earlier humans from the same region, who lived in the Middle Pleistocene. But some features of the skull that were more pronounced in earlier humans, such as the bony ridges over the eyes and a bony prominence at the back of the skull called the nuchal torus, are not as marked in these specimens. Erik Trinkaus says this represents evidence for a process of “gracilisation” - a reduction of bone mass through evolution - that was common to other human groups at the time. And the two specimens from Xuchang have comparatively large braincases - reflecting a trend towards larger brain sizes across the Old World - Europe, Africa and Asia.

One of the ancient Chinese skulls - Xuchang 1 - is at the high end of the scale. Prof Chris Stringer, from London’s Natural History Museum, who was not involved with the study, said the individual had a “remarkable brain size, up there with the largest known Neanderthal and early modern examples”.

As regards any potential relationship with the Denisovans, he said: “Unfortunately, the skulls lack teeth so we cannot make direct comparisons with the large teeth known from Denisova Cave, but another similarly-dated fossil from Xujiayao in China does have Neanderthal-like traits in the ear bones, like Xuchang, and does have large teeth, so these may all represent the same population.

“From genetic data, the Denisovans are believed to have split from the Neanderthal lineage about 400,000 years ago - about the time of the Sima de los Huesos early Neanderthals known from Atapuerca in Spain. So one might expect some level of Neanderthal features in their morphology, added to by evidence of some later interbreeding with the Neanderthals.

“We must hope that ancient DNA can be recovered from these fossils in order to test whether they are Denisovans, or a distinct lineage.”

The skulls were found during excavations at Lingjing, Xuchang County in Henan Province, between 2007 and 2014.