The hollowness of our republic is exposed on a daily basis, but the murder of the social activist and human rights defender, Sabeen Mehmood, on the evening of April 25 in Karachi, is the ultimate proof of it. Many Pakistanis have learnt the hard way that subjects like Hamood-ur-Rehman Commission Report, Inquiry into Kargil War, “Strategic Depth” in Afghanistan, Abbotabad Commission Report , “non-state” actors and the issue of enforced disappearances, among others, are taboo subjects, not be discussed by common people. Recently a new theme has been added to the black list and that is unsilencing Balochistan.

Apparently, Sabeen Mehmood had crossed the “red line” by conducting a discussion on Balochistan with the participation of some Baloch nationalists in a small gathering at the facility created by her for providing a forum for discussing issues of public importance. It is public knowledge that recently a private university in Lahore was stopped from holding discussion on the aforementioned subject. It seems the country’s intelligentsia has no right to hold discussion about the fourth or fifth military operation in Balochistan (in response to alleged nationalist insurgencies) that may have an impact on the country’s future not very dissimilar to the one had by developments in the East Pakistan in 1971. That the elected civilian government remains a silent and powerless spectator during all this says it all about our “republic”. Justice for Sabeen now is the demand of every Pakistani and all of us should keep on pressing for it. The following analysis will provide some context, discuss the root cause and suggest reforms that can permanently stop the recurrence of such tragic incidents.

That our founding fathers wanted Pakistan to be a democratic republic is an established fact. Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who was educated in England and who practiced law in the courts of UK and British India, was a secular jurist and a liberal political thinker. His speech on August 11, 1948, before the Constituent Assembly, clearly underlined his vision of future Pakistan. His early demise, the domination of our polity by the colonial trained bureaucracy and feudal elites and the lack of a strong national liberation movement in the Punjab led to the derailment of the state from a democratic path. The dissolution of the first Constituent Assembly in 1954 was the first coup, but official history books will not reveal this fact to our younger generation. The civil bureaucracy, under the leadership of Ghulam Mohammad, led the said coup but the military was also part of it. The then Commander-In-Chief General Ayub Khan became Defense Minister in the new government. The middle class dominated East Pakistan with majority population they were also being the bastion of popular movement for the creation of Pakistan. They were a hurdle for the institutionalized usurpation of political power by bureaucracy. So the 1956 Constitution clipped its wings by creating One Unit in West Pakistan to counter the population strength of East Pakistan although the ratio still remained 54 & 46 percent. The 1956 Constitution also introduced the principle of parity, which provided for 50 percent representation in the National Assembly for each of the two provinces in the “greater national interest”, thus disenfranchising 4 percent of the population of the Eastern Wing. In any case, after clamping martial law on the country in October 1958, the military dictatorship of General Ayub Khan gave up every pretension of the country being a republic and went on to impose a system of controlled democracy.

After the political and military debacle in East Pakistan the ruling bureaucratic elite were in political retreat. It was in this interval that the elected political leadership could frame and promulgate the 1973 Constitution, making the country in theory a federal parliamentary democratic republic. But this “political ambush” by the elected politicians failed to change the real balance of forces within the state system. That’s why there were two failed coup attempts against the government of Z A Bhutto, and the third one led by General Zia-ul-Haq succeeded in overthrowing the civilian government. Zia’s dictatorship not only deformed the Constitution but also sowed the seed of religious extremism and terrorism.

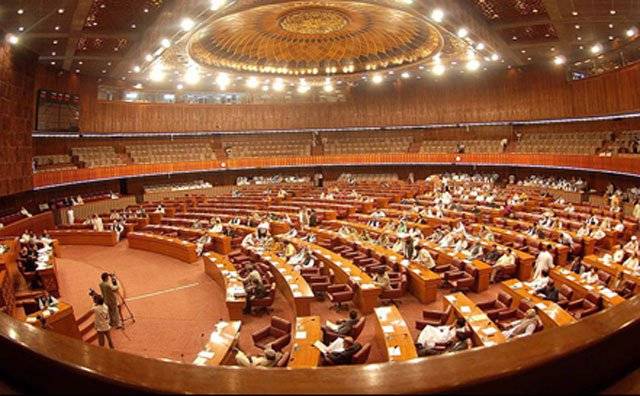

The post Zia “republic” with multiple power centers was weaker than the Weimar Republic of pre-Nazi Germany. General Musharraf then reinforced what Zia started in terms of imposing a system of controlled democracy. Article 6 of the Constitution could not be implemented and military dictators could not be made accountable by the weak civilian system. Successive political governments had a partial or weak control over policy making and resource allocation. The first National Assembly that could complete its constitutional term in the entire history of the country was the one elected in 2008. Every other one was dissolved through unconstitutional machinations by the powerful establishment.

The purpose here is not to absolve civilian governments of their responsibility for the blunders they have been committing. Many of them have mismanaged their rule, missed opportunities and lost credibility. But most of them have been held accountable by courts as well as by the people in elections, and rightly so. How can the challenge of good governance be met without first deciding the question as to who will really rule the country? If the historical record of the country is any thing to go by, it is pretty clear that there were no reluctant coup makers. They were actually waiting in the wings. Zia and Musharraf’s martial laws mutilated the 1973 Constitution beyond recognition. The Charter of Democracy signed between PPP & PML-N in 2006 led to the 18th Constitutional Amendment cleansing the Constitution of many dictatorial deformations to some extent. But much more is required to be done to change the balance of forces in the state system. The non-elected part of the state is too autonomous to be following the lead of the parliament or the elected government.

Political parties of the country need to agree on a new Charter of Democracy to establish a genuine republic in the country. For the political parties to be credible and convincing the new charter has to start with a commitment to reforms within political parties first. For example, political parties should agree on a legal mechanism for holding transparent intra-party elections. The parliamentarians should not receive government funds for development as it breeds corruption. Stringent laws for stopping patronage and promoting meritocracy is the need of the hour. Political leadership needs moral authority and not just law to call the shots in governance. Elections for local government on regular intervals, as enshrined in the Constitution, must be ensured. After this the elected representatives should ensure civilian supremacy on policymaking and resource allocation, according to constitutional provisions. The “deep state” can then be brought within the ambit of the law of the land and stopped from functioning as a state with in the state. It has happened in countries like Indonesia, Philippines, Turkey and many Latin American countries. It can and it should happen in Pakistan, as it is the only path leading to peaceful unity and development.

Thursday, April 18, 2024

Myth of a Republic

Afrasiab Khattak is a retired Senator and an analyst of regional affairs

Stefanos Tsitsipas advances in Barcelona

4:19 PM | April 18, 2024

Met Office predicts more rains across country till April 29

2:51 PM | April 18, 2024

Punjab changes school timings for summer season

1:55 PM | April 18, 2024

Enemies of Pakistan are unable to digest investment in the country: Ataullah Tarar

1:29 PM | April 18, 2024

IHC restores Bushra Bibi's appeal for shifting to Adiala Jail from Bani Gala

1:24 PM | April 18, 2024

Hepatitis Challenge

April 18, 2024

IMF Predictions

April 18, 2024

Wheat War

April 18, 2024

Rail Revival

April 17, 2024

Addressing Climate Change

April 17, 2024

Justice denied

April 18, 2024

AI dilemmas unveiled

April 18, 2024

Tax tangle

April 18, 2024

Workforce inequality

April 17, 2024

New partnerships

April 17, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024