LONDON-Restricted operations at the British Antarctic Survey’s Halley station may have to continue for some time to come.

The base, which ordinarily stays open year-round, is currently closed because of uncertainty over a developing crack in the ice shelf on which it sits.

Scientists are using automated ground instruments and satellites to monitor the fissure from afar, and plan to reoccupy Halley from November.

Whether that is just for the length of the Summer season, though, is unclear.

“That decision will have to be based on our observations; and these processes, because they are ice-related, are often painstakingly slow,” BAS glaciologist Jan De Rydt told BBC News.

The UK has had a permanent presence on the Brunt Ice Shelf since 1956, and scientists would be loath to see their operations routinely reduced to just a few months a year.

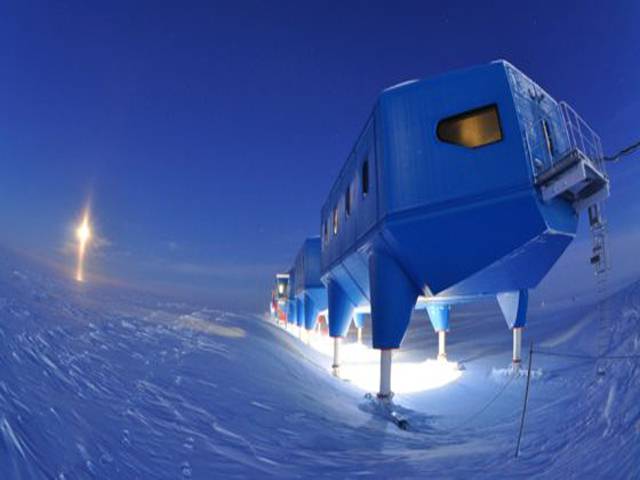

Halley VI, as the base is known in its latest incarnation, will feature in a colourful BBC Horizon documentary on Wednesday.

Filmmaker Natalie Hewit spent three months at the turn of the year recording the huge effort to shift the station’s futuristic-looking buildings to a new location.

Tractors dragged the eight modules a further 23km from the ocean’s edge, to put them in a more secure spot.

“It was an incredible sight,” recalled Natalie. “We have some amazing drone shots, taken from up high, of one of these blue modules moving across the ice, but you can’t see where it is going because this place is so expansive, so huge, so desolate - all the way to the horizon is just white. And it really reminds you how teeny-weeny we are.

“This programme, though, is about more than just moving some buildings; it’s very much about the people who work at the end of the world to do their science.”

Halley base is geared up to be mobile. It has a hydraulic leg and ski system that allows it to be raised above the annual snowfall, and towed. Without this mechanism, the station would eventually be buried and carried to the shelf edge where it would then be dropped into the ocean inside an iceberg.

Halley bases I to V were abandoned to this fate or demolished. The latest design represents a novel solution, and the recent move was its first implementation.

The relocation was initially ordered because some long-dormant chasms in the Brunt Ice Shelf to the south and west of Halley had started lengthening again. This turned out to be serendipitous because a completely different fissure system then opened to the east.

This new crack - dubbed the Halloween Crack because it was first discovered on 31 October last year - propagated rapidly and now extends for about 60km.

It poses no immediate threat to Halley but the uncertainties surrounding its likely future behaviour are what prompted the temporary withdrawal of staff. This was seen as a sensible precaution given the dangers of trying to fly planes in and out of the base during the polar winter, when nights are long and weather conditions deteriorate.

BAS experts now have to decide whether November’s returning teams can once again take up permanent residence or limit their stay to just the length of the southern summer.

The Halloween Crack is propagating roughly eastwards, broadly parallel to the continent, and away from Halley. It is the other end, though, close to the ocean, that is concentrating minds.

This tip is currently held up at a location known as the McDonald Rumples - a raised area of seafloor that catches on the bottom of the floating ice shelf. Dr De Rydt explained: “The Brunt Ice Shelf is pinned at the rumples; it’s where the shelf runs aground. The rumples are an anchor point that keeps everything in place and stable.”

Glaciologists are waiting to see if the crack will break past the rumples, and on which side. They should then get a clearer idea of the longer term reaction of the shelf to the changes that are presently in play.

Ultimately, the Halloween fissure will probably calve a huge iceberg into the ocean.

“In the 1970s, we had a similar event where a crack happened very close to where we see Halloween Crack today,” Dr De Rydt told BBC News.

“That crack ended another 20km or so towards the east of where the tip of Halloween is now. And that created a berg of several thousand square kilometres.”

Halley’s mobility means it should not be anywhere near this great block of ice when it cuts free.