A virulent social media campaign to paint five disappeared activists as blasphemers deserving execution has spotlighted how right-wing efforts to muzzle liberal voices using Pakistan’s draconian laws have found a powerful new platform online.

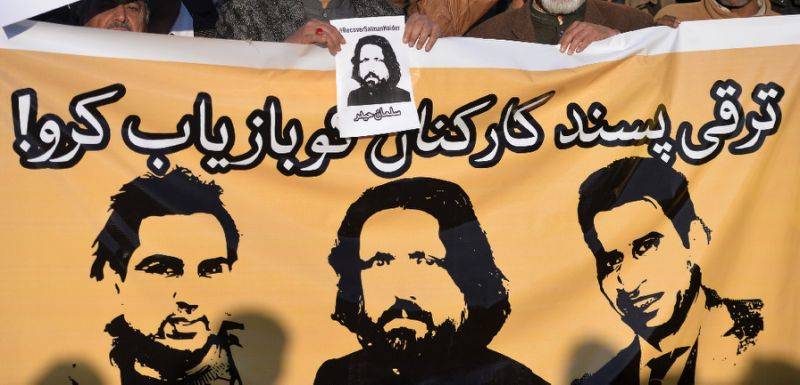

The five men had stood against religious intolerance and at times criticised the powerful security establishment, with several of them running progressive Facebook pages.

They vanished within days of each other earlier this month, sparking fears of a government crackdown. No group has claimed responsibility. Security sources denied being involved.

As publicity surrounding their disappearances grew, with protests in major cities, observers such as Digital Rights Foundation founder Nighat Dad began to notice a worrying trend online.

"There are people trying to label these missing bloggers blasphemers, and the people supporting (them) are being labelled blasphemers," Dad told AFP.

The allegation can be fatal in a country where at least 17 people remain on death row for blasphemy.

Rights groups have long criticised the colonial-era legislation as a vehicle for personal vendettas. Even unproven allegations can result in mob lynching.

And now such accusations targeting the disappeared activists are multiplying on Facebook and Twitter.

"The group of atheists committing blasphemy on Facebook... have been defeated," said a recent post by Pakistan Defence, a powerful pro-military Facebook page run by anonymous right-wing elements which has 7.5 million likes.

The post, liked more than 5,400 times, triggered a flood of threats including one suggesting the activists' "bullet riddled corpses should be found beside any gutter".

Other pages such as ISIPakistan1, with 192,000 Facebook likes, called for such "enemies of Islam" to be "eliminated".

Self-censorship

The attacks are perpetuated by right-wing trolls such as 25-year-old Farhan Virk, who admits he has few real friends but has 54,000 followers on his verified Twitter account.

By re-tweeting the blasphemy charges against the activists, Virk gives them a prominence on social media that can influence the mainstream news agenda.

A number of NGOs and observers believe the campaigns to silence progressive voices are carefully coordinated.

Digital rights activist Dad points to what she says is a periodic surge of new right-wing Twitter accounts with just a handful of followers whose "only purpose is to attack us".

The end result is often self-censorship, with the online attacks following a well-worn pattern.

Journalist Rabia Mehmood criticised Pakistan online after human rights activist Sabeen Mahmud was assassinated in 2015.

Mehmood received a barrage of death and rape threats on Twitter and Facebook, including many from newly created accounts, accusing her of being anti-state and an enemy of Islam.

"Overnight there were tweets warning me that there were bullets with my name on them for criticising the military and the intelligence agencies," she said.

"Since then I have started watching what I say."

The new wave of blasphemy charges that followed the activist disappearances prompted a number of liberal online commentators to close their accounts completely.

Shrinking space for dissent

Pakistan used its legal agreements with Facebook and Twitter to temporarily remove a slew of left-wing accounts in 2014, and enacted a cybercrime law last year that critics say will stifle genuine dissent.

Meanwhile, pages such as Pakistan Defence appear to operate freely, despite content that would appear to contravene basic community standards.

A Twitter spokesman said support teams have been retrained on enforcement policies, "including special sessions on cultural and historical contextualisation of hateful conduct".

Facebook said it routinely worked to "prohibit hateful content and remove credible threats of physical harm".

Observers say the blasphemy allegations against the missing activists have already put their lives in danger of vigilante attack.

In 2011, a liberal governor who criticised the laws was gunned down in Islamabad, while in 2014 a Christian couple falsely accused of desecrating the Koran were killed by a mob, their bodies burned in a brick kiln, to cite just two examples.

"If they come back I don't think they have a life in this country," said Shahzad Ahmed, director of campaign group Bytes For All. "They will have to leave."