The Shakespearean Ides of March symbolise patrimonial coups and unkindest cuts. In Pakistan, the month of March perennially revitalizes the medieval European drama. Pakistan’s history is a story of intrigues, behind the scene deals, coups, elitist politics and inventive nationalism. Pakistan’s Ides started in days leading to 23-24 March 1940 and continues to repeat with alacrity. Truly, they began in 1906, when Urdu speaking leaders of the newly formed league took the reins of the party in their hands in Dacca. Politicians, generals, civil servants and judges as butchers have all been part of this dissection.

With a verdict on Panama close at hand, the nation awaits what according to admissions of the Supreme Court bench would be exemplary/valid for many decades to come; or, will it like the past, be premised on the mindset of necessity? As Pakistan celebrates its 76 years of Lahore Resolution and mourns 60 years of its first impractical constitution, it is opportune to peep into the past and contemplate why the ‘Pakistan that was envisaged’ is not the ‘Pakistan that is’? It is never late to set the clock to its real time.

Let us put the history right. On 23 March 1956, Pakistan adopted its first constitution transforming itself from a Dominion under the British Empire to Islamic Republic of Pakistan. The League adopted Lahore Resolution on 24 March 1940 and not 23 as we are led to believe.

1956 Constitution was the only bright spot in a compromise document built around the Legislative Act of 1953. Apparently, it was a continuation of the Objective Resolution that displaced the League’s Creed. This meant that Muslim League divorced itself from the compulsions of its founding in 1906 at Dacca. Immediately, League lost all support in East Pakistan. The document provided a federal system based on parity between East and West with no upper house. The center could prevail over the two provinces and curtail devolution. It also declared that no law could be passed against the spirit of The Holy Quran and Sunnah and drew a distinction between Muslims and other religions. Breaking away from the British Dominion, 23rd March was declared the Republic Day of Pakistan.

1956 constitution was still born. On 7 October 1958, President Mirza staged a coup, abrogated the constitution and imposed martial law. Twenty days later, General Ayub Khan deposed Mirza and assumed the Presidency. The abrogation opened fissures that ultimately cost the division of Pakistan in 1971. Had a military backed coup not taken place, democracy in due course would have adopted an inclusive course and Pakistan would have been different.

In sharp contrast to Lahore Resolution passed by All India Muslim League in Lahore from 23-24 March 1940, Pakistan’s constitutionalism is a conspicuous disconnect that successive governments in Pakistan failed to address. Pakistan had to pay a heavy cost for resigning the Lahore Resolution to history. Had this Muslim League Creed not been substituted with the Objective Resolution, Pakistan’s evolution rather than a divisive course, would have followed a synergetic and inclusive development. Ideology of Pakistan was inserted much later by Ayub Khan as part of Inventive Nationalism.

Republic Day was meant to celebrate Pakistan’s constitutional tradition and transition from a dominion. Ayub Khan initially changed the celebration to ‘Pakistan and Republic Day’. Later the date of Lahore Resolution was advanced to call it ‘Pakistan Resolution Day’. A military dictator subverted the dates of democratic and constitutional landmarks to eclipse his unconstitutional act of a coup and abrogation of a constitution. This reflected a quest of total control by a dictator who disliked politicians like Prime Minster Hussain Shaheed Suharwardy and A. K. Fazlul Haq. As events proved, this was at a heavy constitutional and political cost. Had the 1956 constitution been given a chance, it could have morphed into an effective document of federalism ensuring integrity of Pakistan. Perhaps the single most pressure on Pakistan to take this course was the US containment policy.

The historical context of the Lahore Resolution is hidden from the people of Pakistan due to insertion of distortions in history such as Pakistan Resolution Day. Deficient of political and nation building logic, successive military and democratic regimes paid lip service to religion in order to hedge elitist interests. Pakistan’s military and civil regimes were always under the watchful radar of the containment strategy. This created deeper and wider fault. 23 March as Pakistan Resolution Day warrants incisive analysis. It represents an exploitive and pliant aspect of Pakistan’s history.

According to K K Aziz, there were 88 variations of the partition of India before Dr. Muhammad Iqbal gave an idea of a Muslim State at his Allahabad address of 1930. This is a first step in distorting history. From 1906 till 1947, the east and west were part of the same struggle. East provided the platform, intellectual inputs and direction. The answer to why they parted ways after the battle was won begins in inventive nationalism. The idea of separatism (following the experience of separation of Bengal) came from Bengal and not Punjab.

The idea was ignored till Allama Iqbal as President of Punjab Muslim League reflected the concept in his famous Allahabad address. Here, he envisioned a North Western Muslim Province within the British Empire of Indian Union. It neither had Bengal nor UP in its sights. The eagerness of predominantly non eastern leadership to espouse this incomplete idea meant that Bengali leaders were resigned to fight their own struggle reflected in the many twists and turns recorded in dissenting notes and speeches of A. K. Fazlul Haq.

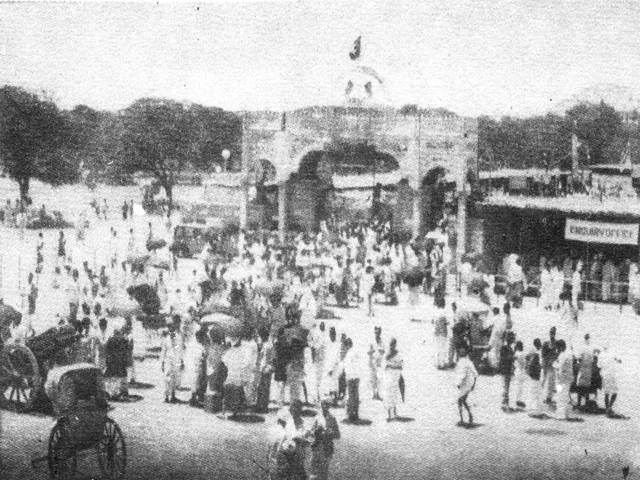

Curiously, North West and Punjab were dominated by Unionists and Congress sympathizers, abhorring the idea of a separate homeland. To the contrary, Bengalis pushed for a Muslim Identity. There was fierce internal politics ranging from intrigues to appeasement that played a role in drafting the Lahore Resolution. A. K. Fazlul Haq, the Chief Minister of United Bengal and Choudhury Khaliquzzaman with reluctant support from Sikandar Hayat Khan of Punjab managed to push through the Lahore Resolution on 24 March 1940. Sikander Hayat was a Unionist and did not support the movement of a separate Muslim State. The final interpretation of the Resolution was left to a committee that ignored the question of ‘States’ within a Union. This was to appease Sikandar Hayat for his support.

It is important to note that the resolution made no mention of religion, had a vague demand of state(s) and focused on Muslim majority areas. This meant that the League’s real constituents, the Muslims in Hindu majority areas were ignored. This relegation later resulted in worst and bloodiest human migrations.

On 24th March 1940 the Lahore Resolution was adopted. The Hindu press cynically called it the Pakistan Resolution. The Sindh Assembly was the first British Indian legislature to pass the resolution in favour of Pakistan. G M Syed, an influential Sindhi activist, revolutionary and Sufi presented it. On 15 April 1941 the Lahore Resolution replaced the original creed in the constitution of the All-India Muslim League.

Post 1947, a cardinal piece of Muslim League’s legal and constitutional history was resigned to history. Had the politicians of Pakistan continued to adhere to this creed after the death of Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s history could have been different.

Punjab’s centrism with a shadow of the UP lobby caused irreparable damage to the federation; yet these are the unfortunate lines on which to the chagrin of East Pakistan, the West Pakistani narrative was built. This also explains why and how Punjab continues to dominate politics in Pakistan.

As Pakistanis, we must remain cognizant to this part of Pakistan’s history. Who knows, one day we may have the opportunity to setting back sails to the original course of history. As Pakistanis, we are bound by our integrity to revisit the Lahore Resolution as the first step to reclaiming Pakistan.

The writer is a political economist and a television anchorperson