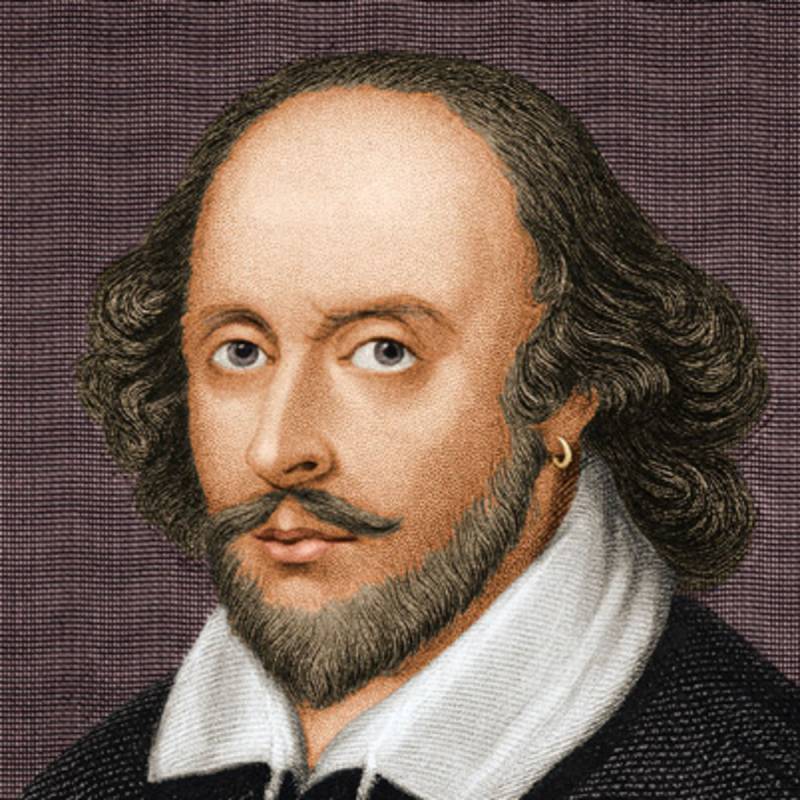

There seems to be a vague feeling that William Shakespeare’s 400th death anniversary, which fell last Saturday, must be a significant event, but there does not seem enough of the feeling that he helped define the world as we know it, because he played a major role; perhaps the most major; in defining the English language, which is the premier lingua franca of the Western culture that has come to dominate the world.

One of the most important features of Shakespeare is that he is both a poet and a playwright. That has meant that he has not only told stories, but has told them beautifully. His use of the English language has helped paper over the fact that he was hardly original. It is one of the staples of a scholarly introduction to a Shakespeare play to explore his sources. His originality lies in how he improved the original story, not in thinking up new versions.

How could someone with such a fecund mind rely so much on original thought by others? Not only was he a product of his age, but also of his profession. It was an age preceding the modern, but no more medieval. When he died, the Reformation was not yet a century old, and the Ottoman Empire was still at the height of its power. It was an era in which the Latin language was the lingua franca of Europe, though only among the educated. Shakespeare knew ‘little Latin and less Greek’, and was peculiarly fitted for the role of the father of a new vernacular, which was ultimately to become a world lingua franca itself. Is it a coincidence that he shares the date of his death anniversary with Miguel Cervantes, the creator of Don Quixote, one of the most memorable creations of the imagination, who not only heralded the coming of the modern novel, but also played a key role in the creation of the Spanish language?

At the time of Shakespeare, Spain was the major European power, and its attempt to subdue England through the Spanish Armada (1588) was something he remembered. This was an area when the Americas had been newly discovered, when Protestant England was fighting Catholic Spain through such privateers as Sir Francis Drake and Sir Martin Frobisher. All this new experience needed a new vocabulary, which Shakespeare gave.

It should not be forgotten that Shakespeare started out as an actor. Then he turned to writing scripts. And for that he ransacked whatever sources he could find. His plays are divided into the Tragedies, the Comedies and the Histories. The Histories, wherein he related the history of England from the time of Cymbeline, down to Henry VIII, had as their source Holinshed’s Chronicles, itself a major historiographical effort. He attempted, and clearly succeeded, in creating a national theatre, to replace the Greek and Roman plays which were then staged much more frequently all over Europe than they are now. He still used Roman themes, borrowing from Plutarch’s Lives of Ancient Greeks and Romans, in the translation by Sir Thomas North.

It is perhaps apt that his death anniversary was marked by the US President, perchance in the UK, on a state visit, dropping in on a rehearsal of one of his most famous plays, Hamlet, at the Globe Theatre, which not only provides the Shakespearean theatrical experience, but is the theatre he worked at. Shakespeare’s language owed its eminence to the power of the British Empire, which was in the process of being founded when he wrote, but when that Empire faded, its place was taken by the USA, which had once been part of that Empire. That the President of the USA is a black may well be reflected in Othello, which is not the only time Shakespeare touched upon race relations. He addressed the Jewish Question through Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. In keeping with the time, Shylock is the villain, but his famous speech (‘If you cut us, do we not bleed?’) applies to all suppressed peoples.

That speech is in prose, which reflects how Shakespeare used prose especially for the comic effect that would please the ‘groundlings’. Shakespearean plays were like Indian films in that they tried to appeal to all tastes. If Hamlet was a tragedy meant to appeal to refined and educated tastes, it also contained the scene in the graveyard with Yorick’s skull. If Macbeth was a tragedy, the doorkeeper in it provided the comic relief.

Some of the universality of Shakespeare has emerged in the 20th and 21st centuries, by the way he is used as a scriptwriter for the movie industry This is not the tribute of one medium to the Old Master of another, but a very real acknowledgement that Shakespeare wrote good scripts. An Indian, Vishal Bhardwaj, has recently made the attempt by changing the setting. He made Haider, a Hindi film, with a plot quite closely following Hamlet, but set in modern-day Kashmir rather than ancient Denmark. Hollywood and Bollywood are evidence that Shakespeare has made the transition from European to world icon.

It is not just that he is the person who reproduced some of the most timeless stories of the world. He is also a very considerable poet. He is rated by some as the greatest English poet ever. Since poetry has assumed some of the characteristics of divine revelation (one needs to look at T.S. Eliot’s theory of ‘the vatic gift’), Shakespeare is something of a prophet of the modern. As the supporters and expounders of ‘modernity’ as the new religion are short of a prophet, Shakespeare fills the vacuum. Of course, Shakespeare only does so for the English language; other languages have their own towering figures to play this role.

The transition of Shakespeare from popular playwright to linguistic icon has taken less than 400 years. The problem is that Shakespeare used what was a very lively and up-to-date idiom, and thus the passage of time has made the language drift from current usage. Shakespeare can only be approached by the modern reader with a glossary. The time has not come where he needs a translator, but as the example of an earlier classic has shown, that too might happen to Stratford-Upon-Avon’s most famous son. There is an excellent translation into modern English of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales by that great Chaucerian scholar, Neville Coghill. Pre-Chaucerian English is clearly a different language, and while four centuries do mean that Shakespeare is not an easy read for the modern reader, it is still possible. However, it can be argued for long it will be, but not that it will be forever.

Perhaps because of that, even though he is a classic, he is avoided. It is possible that his omission from Pakistani courses before post-graduation plays a role in that, but he is also part of the higher Western culture that is avoided by most Westerners, and even more Pakistanis. Just as much as the latest pop song might be preferred over classical music, there is a preference for the latest Hollywood hit than a Shakespearean play. And that perhaps is itself a tragedy of Shakespearean proportions.