Many states that emerged after the end of colonial rule in the 20th century had to face the challenge of acquiring a new national identity. The problem was aggravated by a number of factors. First and foremost was the arbitrary and callous nature of the new state frontiers imposed by the colonial masters in total disregard to the historical and national aspirations of people of former colonies. The colonial powers, while physically leaving their former colonies, still nurtured strong designs for creating a world order that was to be dominated by them and that could cater for their ideological, political and economic interests and keep their rivals at bay. So they had their own vested interests that mostly determined their policy in carving out state frontiers rather than the demands of the national liberation movements. Secondly the ambitious leaders of the newly emerging states, acting quite subjectively, assumed that their states are ready-made modern national states just like the states of their former European masters. They didn’t realize that they have yet to undergo the process of nation building that modern European nations have evolved through over the centuries, something that could be achieved only through historical development and not by administrative order or mere coercion. They failed to appreciate the reality, that yes they had a state of their own, but they had to build a nation for the new state through a historical process of development. This is what landed many newly born states into internal conflicts.

The most sensitive and delicate question was handling of the cultural, ethnic and national diversity existing in these societies from hundreds of years. Now this diversity could not evaporate into thin air by the proclamation of independence by the new states as it had strong roots in the history of these societies. The most sensible and rational way of dealing with this diversity would have been to draw it towards unity by recognizing, respecting and celebrating it, in other words looking for unity in diversity. But in many cases the issue was mishandled by denying the diversity thus negatively provoking it. Ethnic and cultural repression by the bigger and predominant nationality in a state has invariably led to the worsening of the situation by strengthening centrifugal forces.

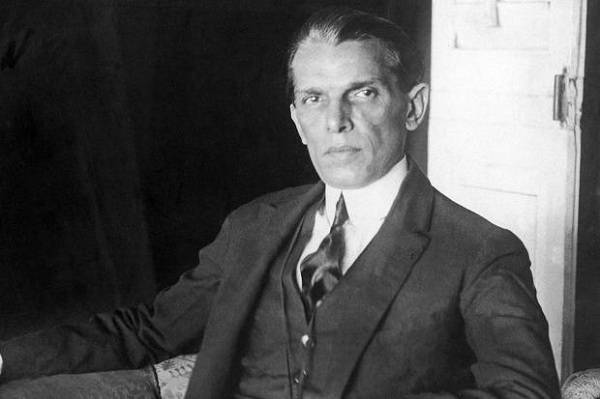

For Pakistan the challenge of national identity was more severe because of its peculiar situation. Pakistan is a completely new state without history of statehood with a deep sense of insecurity as some of the neighboring states challenged its existence. Consequently the policies based on paranoia were bound to lead to unintended consequences. The early demise of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah led to a vacuum which could not be filled by Muslim League as the political party didn’t have strong and popular roots in the areas that were included in Pakistan, except East Bengal as demonstrated by the election results of 1945. The feudal leadership with a strong dependence on civil and military bureaucracy lacked the vision for nation building projects. This failure was fully reflected in the checkered history of constitution making in the country. The Urdu speaking ideologues of the new state originating mostly from Central India could not relate themselves to the local cultures and history. They rejected the cultural and historical realities of the society that constituted Pakistan insisting that Muslim nationhood can take care of every thing. Initially this idea found resonance with Punjabi intelligentsia that was traumatized by the bloody partition of the Punjab on a communal basis. This led to an effort by the Mohajir/Punjabi elites to bulldoze ethnocultural diversity by an enforced uniformity that was bound to be counter-productive. East Pakistan (Bengal) that was the population wise biggest province and had to its credit the most important role in creating the new state became the first casualty of this policy. The Bengalis were shocked to discover that even though they had been the only province of Pakistan that had clearly favored the creation of Pakistan in the crucial election of 1945 and also being the majority population in the country, their language Bengali was not recognized as a national language. On February 21, 1952 state security forces opened fire on a Bengali students’ demonstration in Dacca who were demanding the status of national language for Bengali. A number of students were killed in firing (February 21 is now celebrated every year as International Mother Tongue’s Day by UNESCO in memory of this incident). This was the beginning of the movement for a separate country Bangladesh. Diabolical “ constitutional” schemes like One Unit and Parity further reinforced the trend leading to the tragic events of 1971.

The aforementioned policy of enforced uniformity had extremely negative consequences for religious minorities as well, as it negates pluralism in all its forms. It became a basis for the intolerance that led to extreme marginalization of religious minorities. Male domination and aggressive patriarchy is also an important dimension of this uniformity denying women rights. This is a major factor for our “reverse journey” in terms of implementation of women’s rights. Contraction of socio-cultural mobility of women has been at the core of this religious narrow mindedness.

Unfortunately our ruling elites have not only failed to learn any lesson from the debacle of East Pakistan but they have redoubled their efforts for imposing religious extremism as policy for nation building after 1977. They haven’t hesitated from co-opting extremist Deobandi/Wahabi sectarian ideologies to bulldoze ethnic and cultural diversity. Huge investment of dollars and petro-dollars in propagation of religious extremism during Afghan war has played havoc with our society. Talibanization of Pakhtunkhwa, FATA and now Balochistan and Sindh is clear evidence of this phenomena. Our official history books are devoid of any information about great civilizations of this soil like Indus Valley, Gandahara and Mehargarh. Even the tolerant Islamic traditions of Sufism that travelled to South Asia from Central Asia through the areas that constitute Pakistan do not find any mention in history books. The result is the rise of religious extremism and militancy that has the potential for destroying us as a state and society.

One doesn’t have to be a prophet to predict that failure in implementing National Action Plan and in reimagining our national identity to become a normal, democratic and peaceful state can land us on the trajectory of Iraq, Libya and Syria leading to international isolation and internal implosion. The so called IS is the product of misguided state policies in the Middle East and it will be foolish to expect different results from the similarly misguided policies.