After the arrest of Sheikh Mujib and Bhutto’s slogan of ‘Idhar Hum Udhar Tum’ (we here you there) the public reaction in East Pakistan was immediate and violent. The traditional revolutionary socialite spirit coalesced with the notion of Bengali Nationalism that overflowed the brim. Absence of Bengali leadership (under arrest) created leaders of opportunity and anarchy. Revolts within Bengali servicemen, civil armed forces and police were contagious. Though the military action of 25 March 1971 restored some normalcy, it was not sustainable against a growing discontent. Yet the issue was seen as internal security and not political. An infantry division with no artillery and armour was airlifted from Kharian. Later another infantry division with a depleted armour regiment was airlifted from Quetta. The ORBAT indicates that these forces were for policing operations. War with India was never in reckoning. The fact these formations held on for over nine months is a tribute to field and unit commanders.

Pakistani senior officers in Eastern Command were divisive over the scale and method of military operations against civilians. They were against creating pro Pakistan armed civilian militias that further distanced the local population. Lt. General Yaqub Ali Khan, Major General Shaukat Reza and Major General Khadim Hussain Raja dissented and were removed. GOCs of the two infantry divisions that came as reinforcements had little time for preparations and were inducted immediately into operations. The Pakistani dilemma of a two front war on extra ordinarily expanded exterior lines needed political and strategic reappraisals. These readjustments never happened.

The Soviet-Indo Friendship treaty around July 1971 was a wakeup call. With Soviets coming openly in favour of India, the Pakistani strategic mind got fixed to the containment strategy against USSR and assumed US-British diplomatic and low key military intervention. An important factor in framing this perception was the vociferous presence of the left in anti-Pakistan insurgency with Indian and Soviet support. At the time of crunch, the strategy of pitching Pakistan against godless communism paid no dividends. Like 1965, when the offensive at Chamb was halted on US intervention, Pakistan’s military high command looked for orders elsewhere.

As a stop gap, it was decided to defend nodal points through shrunk interior lines pending international arbitration. As a last resort, the strategy of ‘Defence of East lies in the West’ would be implemented. As time proved, the interventions by Pakistan’s Cold War allies never came and USSR went full throttle in supporting India with military hardware. New Soviet induction in Indian armed forces needed time to be absorbed and Pakistan missed the window somewhere in October 1971. Strong dissuasive military action against India in the West could have restored the balance in Pakistan’s favour. Yes, had Pakistan declared a war on India in October 1971 through offensives in West Pakistan, Indian forays in East would have halted? In strategy, time is of essence. Pakistani military planners were plagued by too many assumptions based on intangibles and less Realpolitik to have acted timely. This lost opportunity strengthened India manifold. Time and tide do not wait for the timid.

The offence in the West was notional. The strike formations were never moved into battle. Spatial gains if any were ceded to lack of decision making in the timeframe that India was imbalanced. One corps commander timidly conceded over 500 villages to Indian forces with the comment that he had a carte blanche to cede territory right up to Marala Link Canal.

Indian strategic planners also had dilemmas. They feared a possible three front war with the Indian Army divided between West and East Pakistan, and the Indo Chinese border. Two Pakistani armoured divisions in West Pakistan posed a serious threat to India. Politically, they also feared the rise of Bengali Nationalism that could, as in the past, lead to a greater Bengali Movement. As a counter move, India accelerated its diplomatic offensive resulting in Pakistan’s isolation. In the interim, while Indian army reorganised, it inducted Tibetan Liberation Army in guise of Mukti Bahini. This had immediate effects as loyalties of Bengalis in the short term fell with India thereby outmanoeuvring the notion of a greater Bengal. Meanwhile India reorganised with new Soviet equipment to wait for winters when a Sino-Indian war would be prohibitive in the snow clad sub-zero terrain. This gamble released mountain divisions for both western and eastern fronts. The Indian diplomatic and strategic manoeuvres were far superior. By reaching into the very womb, India won the war in the minds rather than on the battlefield. The C in C Indian Western Command General Kunhiraman Palat Candeth admitted in his book The Western Front: The indo-Pakistan War, 1971 that “the most critical period was between 8 and 26 October when 1 Corps and 1 Armoured Division were still outside Western Command. Had Pakistan put in a pre-emptive attack during that period, the consequences would have been too dreadful to contemplate and all our efforts would have been trying to correct the adverse situation forced on us”.

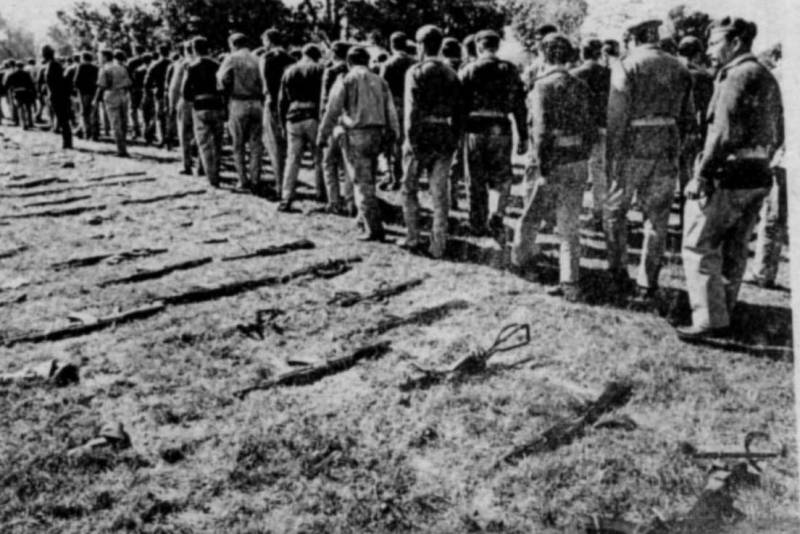

Pakistan unfortunately never saw the window. The infertile minds of the ruling coterie banked too heavily on non-existent support from its allies. Perhaps the most defining moment was the appearance of a nuclear powered Soviet submarine in Bay of Bengal that sent jitters through NATO and USA. It was thereon a military impossibility for about 33,000 riflemen with outdated scores of tanks, depleted field artillery and a lone squadron of Pakistan Air Force to hold on for long a front over 2000 Kms long. At places the force ratio was 1:50. The defensive battle was complicated by the nature of riverine terrain, wide gaps, hostile local population and vulnerable lines of communications. Infiltration by Indian forces and Mukti Bahini through wide gaps was easy. Yet, these contingents of under strength and often isolated units fought valiantly ceding no major success to India on the International border till the day the war was called off. This was the caption of an Indian newspaper on that fateful day of surrender, “For these men, the war ended early. They fought hard but the tide of Indian advance was irresistible. Now they bask in the sun having obeyed the final dreaded order of their commander, Lay down your arms”.

1971 was a disaster in which heads never rolled. Perhaps the biggest lessons of 1971 were empowerment of people, and futility of state franchised armed militias. Pakistan’s establishment has conveniently ignored both.

n The writer is a retired officer of Pakistan Army and a political economist.