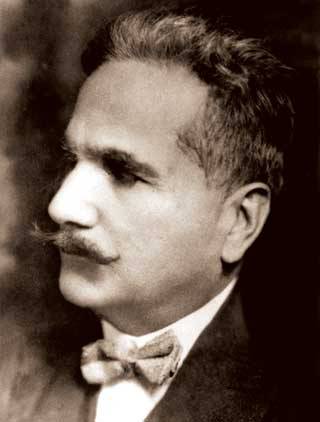

Mohammad Iqbal delivered the presidential address at All India Muslim League’s (AIML) annual session held in Allahabad on 29 December, 1930. The speech delivered at the session has been given the status of Pakistan’s foundational document (alongside the AIML resolution of March 1940).

Proponents of Pakistani Nationalism credit this speech as a bedrock of Muslim Nationalist thought in United India. Progressive and leftist scholars usually point at the context of this speech and the frankly ridiculous circumstances in which it was delivered i.e. the Quorum at the meeting was not met initially, the speech was delivered in English to an audience that only understood the vernacular languages, the split within the ranks of All India Muslim League after Nehru Report and so on.

Among this din of noises, the actual speech and what it stood for, is conveniently forgotten. The speech represents Muslim Nationalist thinking among the intellectuals of the era following the arrival of Simon Commission report in 1930. The commission had been dispatched to India in 1927 for studying constitutional reform and it presented its findings in May 1930. Ahead of the commission’s report, Motilal Nehru had presented his own solution to India’s constitutional crises (in the form of Nehru Report). The Simon Commission report recommended establishment of representative government in Provinces of India. This context is necessary to understand Iqbal’s address in Allahabad.

At the outset of the speech, Iqbal declared his role as a scholar, as opposed to being a politician. He said: “I propose not to guide you in your decisions, but to attempt the humbler task of bringing clearly to your consciousness the main principle which, in my opinion, should determine the general character of these decisions”. The main theme of the speech was Islam and its place alongside nationalism in India. According to Iqbal, ‘India is perhaps the only country in the world where Islam, as a people-building force, has worked at its best. I entertain the highest respect for the customs, laws, religious and social institutions of other communities. Nay, it is my duty, according to the teaching of the Quran, even to defend their places of worship, if need be.’ He was building a case for a multicultural society with an emphasis on Muslim majority.

He then went on to say that: ‘The principle of European democracy cannot be applied to India without recognising the fact of communal groups. The Muslim demand for the creation of a Muslim India within India is, therefore, perfectly justified.’ Iqbal and Muslim intelligentsia of the time was united in opposing democracy because in their conception, democracy meant the rule of majority over a hapless minority. They considered democracy to be a system in which Muslim voices would be confined to the status of a permanent minority within United India.

Iqbal’s solution to this problem was establishment of a Muslim state within United India. He declared: ‘I would like to see the Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, Sind and Baluchistan amalgamated into a single State. Self-government within the British Empire, or without the British Empire, the formation of a consolidated North-West Indian Muslim State appears to me to be the final destiny of the Muslims, at least of North-West India.’ It is worth mentioning that Muslim-majority areas of India were present in Hyderabad and East Bengal as well and Iqbal was not interested in those parts becoming consolidated states. He, however, realised that this idea might alienate non-Muslims living in ‘North-West India’ and assuaged their worries in the following words: ‘The idea need not alarm the Hindus or the British. India is the greatest Muslim country in the world.’ Further in the speech, he proclaimed: ‘Nor should the Hindus fear that the creation of autonomous Muslim states will mean the introduction of a kind of religious rule in such states.’

Iqbal theorised ‘North-West India’ as a frontier region between India and any foreign invaders (since India had historically faced attacks from the Western side). He gave the numbers of Muslim personnel enrolled in Indian army (a legacy of British Racism in the form of the ‘martial races’ theory developed after 1857) and assured that this Muslim force would defend India. In his words, “the North-West Indian Muslims will prove the best defenders of India against a foreign invasion, be that invasion one of ideas or of bayonets.” It is safe to assume that Iqbal was referring to growing Influence of Soviet Russia in parts of Asia and his proposed state ‘within or without the British Empire’ would stop invasion of Communist forces and ideas.

Furthermore, Iqbal wanted a redrawing of India’s map before the constitutional scheme proposed by Simon Commission was to be implemented. He proposed: ‘In view of India’s infinite variety in climates, races, languages, creeds and social systems, the creation of autonomous States, based on the unity of language, race, history, religion and identity of economic interests, is the only possible way to secure a stable constitutional structure in India.’ The Simon Commission report had mentioned that ‘India’s defence cannot be regarded as a matter of purely Indian concern’ necessitating presence of British officers in Indian Army. Iqbal spoke against this imperial policy and demanded further integration of Indian officers in the army. He reminded the audience that ‘If a Federal Government is established, Muslim federal States will willingly agree, for purposes of India’s defence, to the creation of neutral Indian military and naval forces. Such a neutral military force for the defence of India was a reality in the days of Mughal rule. Indeed in the time of Akbar the Indian frontier was, on the whole, defended by armies officered by Hindu generals’.

At the end, Iqbal diagnosed two major problems facing the Indian Muslim community: ‘want of leaders’ and ‘factionalism’. He finished by expressing his gut feeling ‘that in the near future our community may be called upon to adopt an independent line of action to cope with the present crisis. And an independent line of political action, in such a crisis, is possible only to a determined people, possessing a will focalised by a single purpose.’ As it turned out, that ‘single purpose’ was creation of new state/s as theorised by All India Muslim League’s resolution passed ten years after Iqbal’s death, a few hundred metres away from his final resting place in Lahore. However, the state that claims him as ‘philosopher of the nation’ forgot his famous address (bar that single line about North West, not to be confused with Kanye West’s progeny) and progressively hunted out minority communities living inside its boundaries.