Philip Mudd

Nearly two decades into Jack Devine’s career at the CIA, he was tasked with what was then the agency’s largest-ever covert program: the effort to aid the ‘mujahedeen’ fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan. Should the agency take a huge risk by providing the Afghan fighters with sophisticated shoulder-fired antiaircraft missiles? Mr Devine and his colleagues decided that the answer was yes. He remembers walking into the CIA director’s office in 1986 with a report on the controversial introduction of hundreds of these Stingers. “Mr Director,” he recalls saying, “we had a tremendous breakthrough yesterday. We deployed the Stinger and we shot down three helicopters.” Director William Casey, a passionate Cold Warrior, responded: “Jack, this changes it all, doesn’t it?”

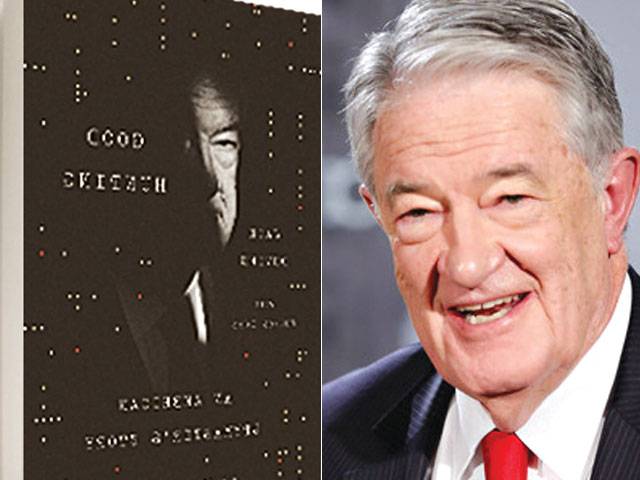

“Good Hunting,” Mr Devine’s memoir, is a refresher course on the breadth of America’s covert campaigns against the spread of Soviet influence and ideology, and Mr Devine’s 32-year career is a microcosm of the secret thrust and counterthrust that defined those years. The son of a blue-collar, Irish-Catholic family from Philadelphia, Mr Devine began at the CIA in the 1960s after reading a book about the agency and sending in a handwritten request for employment. He rose through the ranks, ultimately overseeing the entirety of the agency’s clandestine operations in the mid-1990s.

It seems that he was present at every major CIA operation. He served as a junior case officer in Chile during the 1973 coup that overthrew Salvador Allende’s government. Mr Devine was active during the CIA’s operations against the Medellín cartel, chasing down the notorious Pablo Escobar at a time when drug violence appeared to be taking over Latin America. During the multiyear tug of war after the 1991 Haitian coup, Mr Devine travelled to Port-au-Prince to meet the head of Haiti’s secret police. In a classic story of how behind-the-scenes intelligence relationships sometimes complement more public diplomatic efforts, Mr Devine writes that he was sent by the White House to tell the police chief “to get out of town or the US Government would be visiting him in full force.”

In addition to relating a rich catalog of espionage history and tradecraft, Mr Devine tells the story of the relentless-and often painful-hunt for Soviet moles at the CIA and FBI during his career. He offers particular insights into Aldrich Ames, who remains one of the most damaging turncoats the CIA has ever seen.

Mr Devine first met Ames in 1967, when both were officers in training at CIA headquarters in Langley, Va. The office-mates “spent hours in earnest debate over the great issues of our time.” The two worked together in Rome in the late 1980s: Mr Devine, the station chief there, managed Ames, a midlevel officer. (They even went on a double date.) And in the early 1990s, Ames worked for Mr Devine again, this time at the CIA’s Counter Narcotics Center back at Langley. Mr Devine knew that Ames was a problem employee-he had a drinking issue and a mediocre performance record. But compartmentalization at the agency meant that Mr Devine was not aware of the noose tightening around Ames.

Ames was arrested as a KGB asset in 1994-but only after his revelations to the Russians led to the deaths of many of the CIA’s best foreign agents. Mr Devine, whose pride in his service is prominent throughout the book, is anguished to witness the agency tarnished by a man he had known for so long. “Even though I’d had an inkling this was in the cards, it was a shocker,” Mr Devine writes of seeing Ames’s arrest on television. “His arrest led to one of the lowest morale moments in the history of the CIA.”

“Good Hunting” also reveals some of the downsides of the spy business, from the dangers of moving a family from assignment to assignment to the challenges of implementing the White House’s foreign policies. Mr Devine lived through the infamous arms-for-hostages deal in the 1980s, in which the US sold weapons to Iran and then used the proceeds to fund guerrilla operations in Nicaragua. The lesson of the Iran-Contra affair, he argues, is that even a well-designed covert campaign will fail without a broader US government strategy that includes other instruments of power, from diplomacy to foreign aid to military might. Spies cannot carry a policy alone. And they certainly can’t succeed without some wellspring of support in the countries where they are trying to change national opinions or drive revolts against ruling powers.

The book concludes with a few chapters that veer sharply from Mr Devine’s illuminating stories from the field. In these, he explains his post-CIA career building a business-intelligence enterprise, the Arkin Group, and then offers his views on an array of foreign-policy problems. On both the Iraq war and the CIA’s interrogation of al Qaeda prisoners at its secret prisons, Mr Devine suggests that he would have made better choices than Bush administration politicians and current CIA executives. “As it happens,” he writes, “I saw the disastrous Iraq war coming.” Perhaps he did, but this comes across as Monday-morning quarterbacking. A similar sense of complacency sometimes overshadows Mr Devine’s observations on the bureaucratic machinations among other Washington agencies, where he too often portrays the CIA as the good guys.

These flaws, though, do not obscure this memoir of what life was like in the CIA’s clandestine shadows before 9/11 changed the intelligence business and put the agency on the front pages, for both its triumphs and its deficiencies. “Good Hunting” is also a cautionary tale: While the age of counterterrorism might have led the CIA to move into a new world of airstrikes and enhanced interrogations, the classic skills of spotting, developing and recruiting spies remain critical. Those who hold the secrets America needs to know are human beings. And one of the few ways to understand potential adversaries is to recruit them.

Mr Mudd was deputy director of the CIA Counterterrorist Center, 2003-05, and senior intelligence adviser at the FBI, 2009-10. He is now director of enterprise risk at SouthernSun Asset Management. –Wall Street Journal

Friday, November 22, 2024

Secret Agent Man

Caption: Secret Agent Man

Undersiege Again

November 22, 2024

Cartoon

November 22, 2024

Declining Bilateral Ties

November 22, 2024

Smoggy Governance

November 22, 2024

Actionable Dialogue

November 22, 2024

-

Hunger crisis to increase in South Sudan, warns UN

-

Hunger crisis to increase in South Sudan, warns UN

-

Pakistan’s judiciary champions climate justice at COP29 in Baku

-

Punjab struggles with persistent smog as Met Office forecast rainfall

-

Punjab residents face escalating smog crisis as pollution levels soar across country

-

Qatar says Hamas 'no longer welcome' in Gulf state

Land of Vigilantes

November 21, 2024

United in Genocide

November 21, 2024

Finally Fighting Back

November 21, 2024

Digital Stagnation

November 20, 2024

Xi’s Red Lines

November 20, 2024

Independent Supreme Court

November 21, 2024

Fat Loss Fantasy

November 21, 2024

Tackle Corruption Within School Boards

November 20, 2024

To Be Opportunistic

November 20, 2024

Democratic Backsliding

November 20, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024