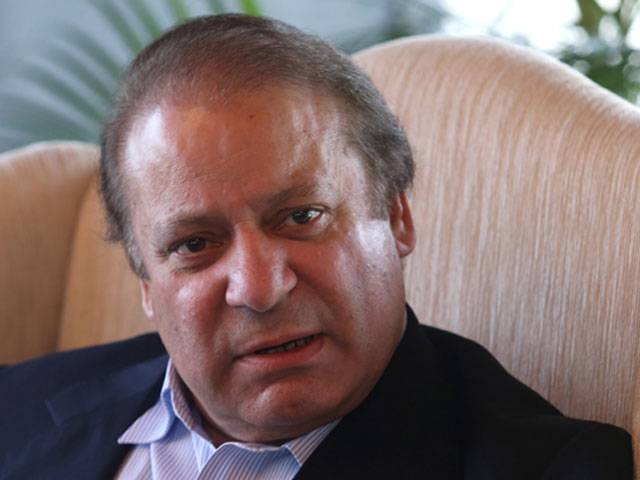

NEW YORK - After his landslide victory in last year’s elections, Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif unsuccessfully tried to emulate Turkey’s Recep Erdogan in countering the Army’s political might, and he now risks sharing the fate of Egyptian President Muhammad Morsi, who was ousted by the Army after the 2013 protests, a report in a major US paper said on Wednesday.

“Sharif is finding out the hard way that the success of Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan in defanging the Generals is more of a rare exception than a workable model to follow,”Yaroslav Trofimov, an award-winning author and journalist wrote in The Wall Street Journal.

“His (Sharif’s) predicament shows just how hard it is for elected politicians to challenge the ‘deep state’ of the military and security establishment that forms a bedrock of power in countries from Algeria to Bangladesh.

“With downtown Islamabad taken over by protesters baying for his resignation, Sharif increasingly risks following another example—that of Muhammad Morsi, the Egyptian President who was ousted by the Army after similar protests in Cairo last year, just a year after winning the popular vote,” Torifemov wrote his op-ed article.

“The Pakistani Army, instead of unconditionally backing the elected Prime Minister as protesters overran Islamabad’s government quarter in late August and erected a tent City modelled on Cairo’s Tahrir Square or Kiev’s Maidan, has positioned itself as an essentially independent third force, publicly demanding that both sides avoid violence.”

“Even a message of neutrality in this game tilts the balance against the government. The dice is loaded against Sharif,” Rasool Bakhsh Rais,Director-General of the Institute of Strategic Studies, was quoted as stating.

“He started out as an Erdogan, but I am afraid he may end up as a Morsi. Very likely.”

Defence Minister Khawaja Asif, a close Sharif aide, was cited as stating that despite recent “jolts,” there is “absolutely no damage” in the civilian government’s relations with the military. But he acknowledged that the Turkish model of asserting civilian control isn’t applicable to Pakistan anymore, at least not for now, according to the Journal.

Erdogan moved to strip the Turkish Army of political power only after years of rapid economic growth and rising living standards solidified his support base, it was pointed out.

“Pakistan’s economy, by contrast, remains sluggish and Sharif can point to few major successes in his term,” the paper said.

“The Turkish ruling party has delivered to the people of Turkey, and this gives them a lot of leverage,” Asif was quoted as saying. “If we are given time, as they had, for more than a decade, and we are able to perform and we are judged by our performance in the 3½ years until the end of our term, then perhaps the political forces of democracy will be much more strengthened.”

“Whether Sharif has that time, however, is uncertain at best,” Torifemov wrote.

“The Pakistani and Egyptian militaries are similar in many ways: Both enjoy huge US funding and run vast business empires sheltered from civilian oversight. But the Pakistani Army, which ruled the country for half of its history, is still recovering from the 1999 coup that ended Sharif’s previous term in office. For now, at least, it is reluctant to openly seize power, knowing how unpopular such a takeover would be.

“This means that Sharif could survive the current protests, launched by Opposition politician Imran Khan and Islamic cleric Tahir ul Qadri, who claim that last year’s elections were illegitimate because of fraud and violations of electoral law. Messrs. Khan and Qadri, as well as the Army, deny allegations by Sharif’s supporters that the protests are secretly orchestrated by the military.”Even if Sharif clings to office for now, he is likely to limp on as a much diminished figure, vulnerable to the kind of intrigues that the Army, headquartered in the city of Rawalpindi, repeatedly used to unravel past Pakistani governments from behind the scenes.”

Following the latest protests, “the balance of power…rests not in Islamabad, but rests unfortunately in Rawalpindi,” Senator Raza Rabbani of the Pakistan Peoples Party, which Sharif in the current standoff, told Parliament last week.” Sharif, to be fair, wasn’t nearly as reckless as Egypt’s Morsi. Within a few months of taking office, the Egyptian President alienated all the main political forces outside his Muslim Brotherhood, seized legislative powers and infuriated the Egyptian Army by backing Islamist rebels in Syria. He even embraced Egypt’s own former Islamist terrorists, including those involved in the 1981 assassination of President Anwar Sadat,” the article said.

“Yet Sharif didn’t come close to emulating Erdogan’s patience, either.

Almost immediately after assuming power in June 2013, Sharif stubbornly pressed for a treason trial of Pervez Musharraf, the former Army chief who ousted and imprisoned him in 1999 and who now faces the death penalty. Sharif also irked the Army by trying to take over its traditional oversight of relations with India and Afghanistan, and by backing a private TV channel network that accused the military’s Inter-Services Intelligence spy agency of trying to assassinate its star anchorman. As a result, he has quickly found himself in open conflict with the Army chief whom he picked in November. (Morsi, too,was overthrown by the supposedly pliable Army chief he himself had appointed.)”

“The Prime Minister is very fond of shooting himself in the foot,” retired Maj. Gen. Athar Abbas, who was the Pakistani military’s chief spokesman until 2012, was quoted as saying.

“He has fallen out with the Army, and the Army has fallen out with him…In this environment, if you try to clip the wings of the Army, the Army will react—and the Army has reacted.”

Tuesday, May 20, 2025

Nawaz tried to emulate Erdogan, now risks sharing fate of Morsi: WSJ

PM orders swift implementation of FBR reforms, anti-tax evasion measures

3:48 PM | May 20, 2025

EU approves its 17th sanctions package against Russia

3:36 PM | May 20, 2025

Pakistan, India DGMOs agree on gradual troop pullback by May 30

2:59 PM | May 20, 2025

Govt declares public holiday on May 28 to mark Youm-e-Takbeer

2:40 PM | May 20, 2025

Pakistan plans to secure $4.9bn in commercial loans for FY2025-26

2:33 PM | May 20, 2025

-

Lahore emerges among safest global cities in Numbeo 2025 index

-

Lahore emerges among safest global cities in Numbeo 2025 index

-

India’s suspension of Indus Water Treaty legally baseless

-

Seventh polio case reported in Pakistan amid nationwide vaccination drive

-

Pakistan reports sixth polio case of 2025

-

PTA begins issuing VPN licences to regulate usage

The Wider War

May 20, 2025

Margalla on Fire

May 20, 2025

Defeated and Depressed

May 20, 2025

Regional Reset

May 19, 2025

Peak Potential

May 19, 2025

Worse than Anarchy

May 20, 2025

Salute to our Air Force

May 20, 2025

An Unbreakable Wall

May 20, 2025

Profiteering Milk

May 20, 2025

Rewriting the Rules

May 20, 2025

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2025