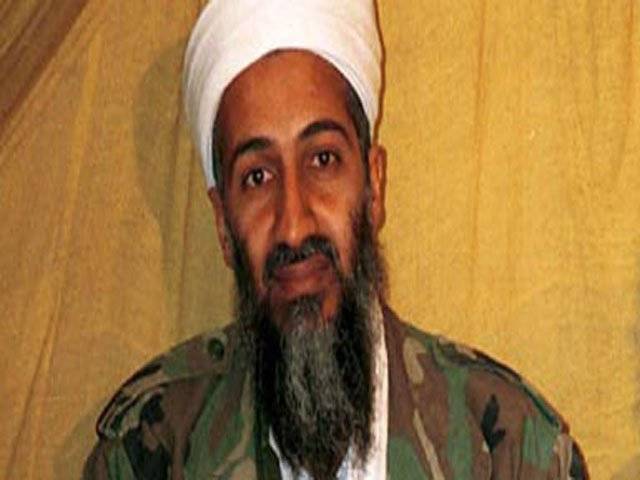

If the $5m price the US put on Osama bin Ladens head in 1998 had led to his immediate capture and disabled al-Qaeda, it would have been the bargain of the millennium. Assuming that the September 11 2001 attacks would not have happened without bin Laden, and that the Afghanistan and Iraq wars would not have happened without September 11, the al-Qaeda leader directly cost American taxpayers more than $2,000bn and the indirect burden may be much higher. The contentious business of estimating the bill for September 11 has become a thriving cottage industry. The direct costs of the Afghan and Iraq operations are the easier part. The Congressional Research Service, Capitol Hills non-partisan think-tank, recently calculated that Congress had appropriated $1,283bn since 2001 on top of its usual military expenditure without adjusting for inflation and debt interest. The CRS estimates the costs will total $1,800bn by 2021. If US boots are removed from the ground in Iraq and Afghanistan as planned and the spending scaled down, those costs are large but not crippling: $1,283bn is less than 10 per cent of the current federal debt. But the so-called war on terror also left the US with new commitments which may be hard to cut. Domestic anti-terror spending surged after the Department of Homeland Security was founded in 2002 the first new government department since the creation of Veterans Affairs in 1989. The need to be seen protecting the home front has apparently extended political impregnability over another big chunk of the federal budget. The recent fiscal proposal by Paul Ryan, Republican chairman of the House of Representatives budget committee, slashed other spending by politically improbable amounts but left homeland security and underlying defence spending largely intact. A paper by John Mueller at Ohio State university and Mark Stewart at Newcastle University in New South Wales, Australia, argues this response has been expensive and excessive. The authors say the direct cost of extra homeland security expenditure between 2002 and 2011, mainly by the federal government, was $690bn in todays money, with passenger delays from extra screening and other indirect costs adding another $417bn. In 2009, the total burden came to nearly 1 per cent of gross domestic product. Using conservative estimates for the costs of property and life saved, the authors say much of the money is wasted. To be cost-effective, the spending would have to prevent or deter four attacks a day of the type that was foiled last year in Times Square in New York. Security concerns that happen to rise to the top of the agenda are serviced without much in the way of full evaluation, Profs Mueller and Stewart say. Security trumps economics. Meanwhile, other evils are neglected: homeland security expenditure now exceeds US spending to combat all other forms of crime. More uncertain is the wider impact of bin Laden on the US economy. Despite fears at the time, the shock of September 11 itself did not cause a global slump indeed, in November 2001 the US economy exited the shallow recession that had followed the bursting of the technology bubble the previous year. Moreover, defying concerns that the ensuing security clampdown would throw sand in the wheels of globalisation, world trade picked up speed again until the global financial crisis of 2008. Though the US demanded of trading partners more rigorous security procedures such as screening shipping containers, the ensuing overhaul of freight and customs procedures in some developing countries made border crossings and ports more efficient. World Bank researchers found that in Pakistan, the time taken to clear an export consignment dropped from 31 to 22 days and the overall cost to process a container almost halved. Some economists blame cuts in interest rates by the Federal Reserve in response to September 11 for inflating the credit bubble of the 2000s. But it was from 2004 onwards, when rates were held low despite a recovering world economy, when housing and other bubbles really got out of control. Joseph Stiglitz, Columbia University professor and Nobel laureate, is probably on firmer ground when he says it was the Iraq war that hurt US incomes by pushing the price of oil higher and provoking overly loose monetary policy. Together with Linda Bilmes, a Harvard academic, Prof Stiglitz has estimated the Iraq war alone to have inflicted at least $3,000bn worth of damage on the US economy. They also argue that public spending to fund the war was diverted from productive domestic areas like research and development, and that it crowded out private investment. Finally, bin Laden may have been inadvertently responsible for potentially weakening the legal framework for global trade and wasting an awful lot of bureaucrats time. The so-called Doha round of trade talks was launched by ministers in Qatar in November 2001, the previous attempt having failed disastrously in Seattle in 1999. Enthusiasts for a new round, such as the then US trade representative Robert Zoellick, argued for a display of global solidarity following September 11. Zoellick and the other enthusiasts took advantage of the need to show unity of purpose, says Claude Barfield, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. It may well have been the tipping point. Opposition at the time weakened: the vocal anti-globalisation movement out in force at Seattle and other international meetings almost completely disappeared, at least in the US, for years. But nearly a decade later, with the initial glow of fervour long extinguished, the negotiations are deadlocked, with the US in conflict with India and China over farm and industrial tariffs. Participants have begun to talk openly about radically scaling down the original plan, in which case the round will have weakened rather than strengthened the multilateral trading system. In the end, the one-off costs of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars provoked by September 11 turned out to be much higher than first predicted, whereas the ongoing damage to the global economy was probably rather less than feared. Bin Laden may have landed a lot of costs on the shoulders of American taxpayers, but he conspicuously failed to end western capitalism as we know it. (The Financial Times)

Sunday, May 19, 2024

Osama cost US taxpayers over $2,000bn: report

Slovak PM shooting: Suspect in detention

May 19, 2024

Flash floods kill 50 in Afghanistan

May 19, 2024

Sports & Genocide

May 18, 2024

Healing AJK

May 18, 2024

A New World Order

May 18, 2024

Tobacco Toll

May 17, 2024

Rushed Reforms

May 17, 2024

Continuing Narrative of Nakba

May 18, 2024

Teacher Struggles

May 18, 2024

No Filers out of Reach

May 18, 2024

Hoax of Inflation Coming Down

May 17, 2024

Rising Inflation

May 17, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Advertisement

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024