There are a number and variety of mosques in Multan. Most of these mosques are tomb-mosques. Two such mosques are known as ‘Sawi’ or green mosques. The larger sawi mosque is comparatively recent, while the smaller one is old and belongs to Akbar’s period. The older, Lilliputian mosque is not very well known and most people who live around it call it a maqbarah (tomb) rather than a mosque. It is situated in an extremely populated area.

Multan is situated about 198 miles (312 kilometers) south-east of Lahore. The city is built on a mound just east of the Chenab River which once flowed very close to it. Multan was formerly called Kashtpur, Hanspur, Bagpur, Sanb (or Sanbpur) and finally Mulasthan. It gets its name from the graven-image of the sun-god temple, an opulent shrine of the pre-Muslim period.

Muslim forces during the reign of the first caliph Abu Bakr in 664, with Muhallab the Arab general, penetrated the ancient capital of Malli. No endeavour was made, however, to subjugate the Indian territory permanently and merge it with the Muslim empire.

It fell finally to the Muslims in 712; for three centuries it remained the outpost of Islam in India. In the tenth century it became a centre of the Qaramatian heretics.

Abu’l Qasim, the earliest known Arab geographer, better known as Ibn Khurdadbih, characterizes the city of Multan by the name of Farj, found colossal aggregates of gold in the city which was henceforth dubbed by the Arabs as the ‘House of Gold’.

Al-Mas’udi (Abu’l Hasan Ali al-Mas’udi), Arab historian and traveler known as the Herodotus of the Arabs, visited this city in 915. In his work The Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems, (completed 942), he writes of Multan: “It is a stalwart and one of the most puissant frontier places of Musalmans. In its purlieus there are a hundred and twenty thousand towns and villages.”

Both Istakhri and Ibn Hauqal speak of Multan as a large, embattled, and invulnerable city, about half the size of Mansura, the ancient capital of Muslim Sindh. The ensuing citation of Multan is made by the celebrated Arab geographer Abu Rihan al-Biruni. According to him, “The city of Mulasthana was taken by Mahmud Ghazn in 1005 when he routed the Qaramatians. In 1193 the city was vanquished by Shihab al-Din Muhammed Ghauri.”

When Shihab al-Din died in 1205, Qabacha was governor of Multan. In 1217 he lost it to Shams al-Din Iltutmish. After Iltutmish, Multan was seized by the Langahs who remained in authority till the beginning of the sixteenth century.

In 1526, the city was taken by Shah Husain (Hasan?) Arghun, a protégé of Babur. On Babur’s death, his son Humayun had to relinquish Mutan to his brother Mirza Kamran. During Humayun’s ostracism, Sher Shah Suri attacked Multan and gained control of it. Sher Shah Suri was an august magnifico and with his command over great mercantile cities like Peshawar and Lahore he developed trade with the countries of central Asia and northern China. He connected Multan with Lahore by road and planted orchards on the way to refresh tired travelers.

Multan was captured by Akbar during his reign and remained with the Mughals till 1738. It had its most prosperous period during the reign of Aurangzeb. In 1738-39, the city was ransacked by Nadir Shah. Ranjit Singh invaded it in 1818. This was a bad phase.

Despite the fact that the whole of the indo-Pakistan Subcontinent remained architecturally under the sway and authority of Delhi, two cities of the Punjab, Lahore and Multan, developed their own styles. The most conspicuous reason for this autonomous development was that it was by virtue of these two cities that Islam penetrated the Subcontinent.

Of these Multan was the premier town to come under the influence of Islam through the punitive the early eighth century. Afterwards, southern Iran to which it had ready access by sea as well as by land. Much of its architectural constitution was therefore sculpted by Iran rather than India. Multan’s architectural tiles and minor arts still testify to these historic contracts.

The architecture of the Punjab used mainly brick. In the absence of fine stone, which was not readily available, brickwork of phenomenal characteristics was produced in Multan, which after Iran, remain second to none.

Nowhere else in Pakistan does woodwork have a role in architecture equal to that in Multan and its environs.

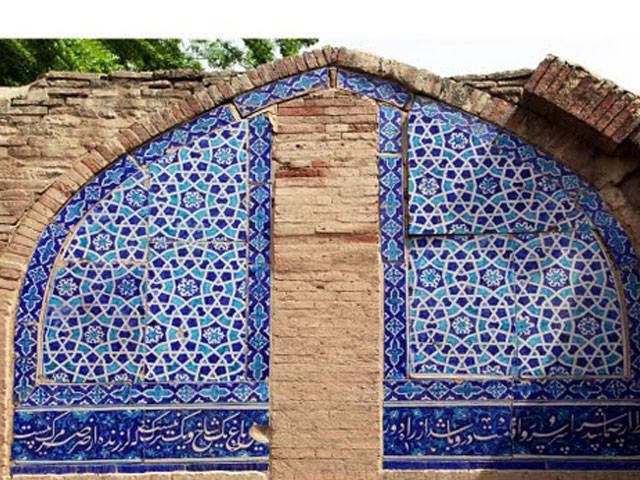

Doorways, windows, oriel and bay; and overhanging balconies, all lavishly carved were also executed in wood. In addition parts of the buildings were decorated with painted plaster or stucco with a paneling of glazed encaustic chromatic tiles in brilliant purple, deep blue and turquoise on a white ground.

The mausoleums in Multan are not of emperors or kings but of saintly personages. Similarly its mosques owe little to the generosity, devotion or devoutness of the rulers. The construction of these monuments is from the middle of the twelfth century to the advent of the fourteenth century. These monuments have suffered badly at the hands of the Auqaf wizards. Though their original character has been assassinated and they have become ersatz, nevertheless, in certain aspects they have managed to retain their pristine traits.

The locality where the old Sawi mosque is situated is recognized as Muhallah or Kotla Taulay Khan. Multan, it may be mentioned here, has the distinction of being the birth place of several eminent dignitaries in history. It is believed that one of the Tughlaq rulers was born here and Taulay Khan is a corruption of Tughlaq Khan.

Muhallah Taulay Khan extends and reaches north-west of the mausoleum of Shah Rukn al-Din Alam. It is in this area that the mosque in question is located. The Sawi mosque is built on a dual platform, each nearly one meter high and approached by an ‘L’ shaped diminutive flight of steps the upper steps having sloping jambs towards the end, showing some Hindu influence. The walls on the north and south have rectangular panels incorporating blind arches. Each of these panels has a saw tooth moulding as the architrave, while the arches are provided with a painted pattern of grille work within the arches. Above these panels, at the top of the wall are blind merlons and embrasures externally alone.

Directly opposite the entrance is the mihrab enclosed within a rectangular fame. Its flanking side walls are horizontally segregated into two longish superfluous panels. Each contains indented rectangular panels which in turn have recessed blind and blunt arches dealt with in the same manner as the exterior. The wall at the top is crenellated. At the end of these walls are circular tapering bastions or round buttresses each crowned with a domical termination but void of any kiosk or pinnacle or burj.

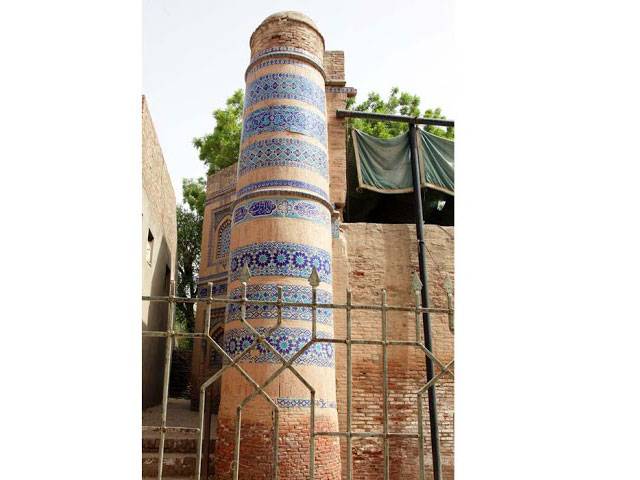

The mosque is built with petite archetypal Mughal bricks which now stand exposed sporadically except on the wall with the mihrab. Since the mosque is Lilliputian in dimensions but considerably elevated on two platforms it has a predominant accent on verticality. The ornamentation is done, for the most part, in tiles and brickwork. Arches and round buttresses are particularly noteworthy for grilles, diapers, geometric patterns and floral motifs. Original tile work survives on the round buttresses, in friezes and patches on the surfaces of certain graves.

The Sawi masjid is not exclusively a mosque but a tomb mosque like many others in the city of Multan. It has a conspicuous mihrab but then immediately in front of it there are a couple of graves leaving room only for a single row of people to offer salah. The court of the mosque is very small measuring 4.10 x 4.80 meters, containing several graves of varying dimensions spread at sporadic intervals.

Though its façade, particularly the door jambs and steps have been influenced to some degree by Hindu influence, the possibility of Tughlaq influence cannot be ruled out either. Tapering corner minarets, turrets, bastions and buttresses were typical of Taghlaq vogue. History does not suggest any exact date of this mosque but keeping its various aspects in perspective, it seems to have been built in the Akbar’s period between 1555-65.

As noted above there are several graves in the sahn of the mosque but one in front of the mihrab and almost in the middle of the sahn is particularly distinctive. It has a large marble katabah or tombstone carrying the epitaph. The slab is fixed on the head side and bears a long inscription in nastaliq style on both sides in Persian verse. The inscription tells us of one Safar Quli who died on the tenth of Sha’ban 999 hijra. Surprisingly, on the back of this slab the name of the month is not given, instead it says shahoor i.e. months and the date given in wourds is tis’a o alif i.e. 1009 Hijra while in numerical it remains 999. Probably Safar Quli died in the year 999 and someone by the name of Zakariyya bin Ustad Muhammed, son of Jeevan composed the verses and installed the slab in 1009 A.H. the name of the poet appears in the last couplet.

The credit for the verses on the front of the katabah is claimed by one Hamiyyat Allah of Balharre. His name also appears in the last of the couplets. I have not been able to identify any town by this name. the geographical location of Balharre remains an unsolved perplexity.

There are many other inscriptions in and outside the mosque mostly in white letters on azure ceramic tiles. Nearly all of them are severely impaired and mutilated. In most cases their rearrangement while repairing by the local people has led to further damage. It is almost impossible to decipher them albeit most of these fragments are original. In spite of being very small the mosque is worth visiting as it combines Saljuq and Mughal architectural features in a very intriguing manner.