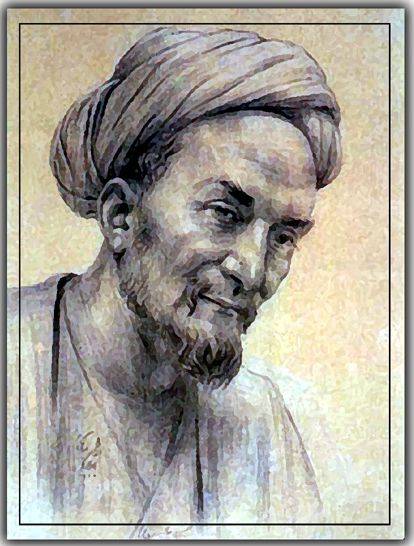

The thirteenth-century poet Saadi, is regarded as one of the greatest figures in Persian literature. He is best-known for his chief works Bustan, or The Orchard and Gulistan, or The Rose Garden. Both of these works are filled with semi-autobiographical stories, philosophical meditations, and sections of practical wisdom, humorous anecdotes and observations. The books are appreciated not only for their elegant language and entertaining style, but also for their role as a rich source of information about the culture in which Saadi lived and worked. It is essential to highlight how in order to “preach morality” the choice of linguistic facility and writing style could vary. Where Baba Bulleh Shah and Muhammad Baksh would choose to philosophize wisdom in an organic and a very domestic style, there Saadi’s language and style as compared to them is very grand and regal.

Saadi’s speech and style incorporates short phrases, as shorter phrases tend to have a lasting impact upon one’s mind as compared to long, convoluted explanations; the style is also such that it poses questions within the text that jolt the inner consciousness of the individual; and, it establishes arguments that make Saadi’s message regarding human virtues more concrete and credible, establishing it on solid moral foundations.

While the writings of Saadi have been a central part in Iranian literature for more than seven hundred years, English translations of his works did not appear until Victorian times. Critics say that his writing style is “impossible to imitate”. The lyrical and poetic expression in writing is coupled with a sermonizing tone which establishes the pronounced idea very firmly, grounding it with utmost authorization and endorsement.

While explaining benevolence as a virtue, Saadi writes:

“Give now of thy gold and bounty, for eventually it will pass from thy grasp. Open the door of thy treasure today, for tomorrow the keep will not be in thy hands”.

The “give now” in the sentence is representative of a certain sense of confidence and conviction from Saadi’s side and this firmity in tone is what can be seen throughout the text of Gulistan.

He says:

“Drive not the poor man empty from thy doors lest thou should wander before the doors of strangers.”

It is imperative to mention how in medieval times the firm tone had to be expressed through a dictatorial and sermonizing linguistic expression, to ensure that the readership/audiences be moved by what was rightly being said.

Another observation about the language and the writing style of Saadi is that each chapter in the boo discusses a virtue which is explained in poetic couplets followed by various “stories”. Each story explains a short tale deliberating upon a moral; the tale/story is ended by a “concluding comment” by Saadi to help the readership understand the idea better. For instance, while extolling upon the idea of benevolence, one of the stories is named as A Story Illustrating Doing Good to Evil, the story itself is spread over a couple of lines in biblical expression and it is summed up by a concluding comment which says:

“Follow the path of righteousness and if thou stand on thy feet, stretch out thy hand to them that are fallen”.

Likewise, in The Story of a Man and A Thirsty Dog from the same chapter has a concluding comment as well:

“Be lenient with thy slave, for he may one day become a king, like a pawn, that becomes the queen”.

These concluding comments endorse the essence that Saadi emphasizes upon.

It is important to be understood that the biblical expression, beautiful diction and sermonizing tone, does not make the text look dominating and/or imposing, it has a subtle tinge to it— but this subtleness does not evade the firmness needed to preach the essence of the virtues. In order to preach, one’s tone and linguistic facility ought to be firm, certain and well-grounded. This is seen in the explanation of gratitude as a virtue:

“O self-worshipper! Why lookest thou not to God, Who giveth power to thy hand?”

Apart from such arguments and questions posed by Saadi that make his writing style jolt one’s consciousness, there are constant premonitions in the text that caution the readership too:

“He made thee pure; therefore, be pure- it is unworthy to die impure by sin. Let not the dust remain on the mirror for once grown dull, it will never again polish”.

Talking about repentance, Saadi’s speech is short and the tone is not pliable, it does not supplicate ideas or implore the readership, rather it is slightly dictatorial in nature. This establishes that Saadi wants to convey his message regarding the virtue in sheer veracity:

“If fifty years of thy life have passed, esteem as a precious boon the few that remain. While still thou has the power of speech, close not thy lips from the praise of God”.

The oratory style of Saadi is what makes his stance well-grounded and convincing— long explanations usually do not stand any grounds and tend to lose their value. Saadi’s phrases and his linguistic facility are concise in nature, and do not sound imposing or infringing. The sermonizing tone helps to put emphasis and endorsement upon the place that needs to be given attention. This helps in better decipherment of the morals that are being preached, making his pronouncements valuable and impactful to individual minds without fading in time and history.

Saadi’s works connect us to our deepest humanity. They help us explore the humanity within us despite our individual demons that make us chase materiality in this world of blackberries and computers. It serves a reformative purpose by forging within us the need to nurture that seed of goodness which is inherently present within all—it might be slow to blossom, but once this veritable goodness is concretized, it would be secure in its attachment to us, making us walk on the path of altruism, contributing to fashioning a world where love and a selfless disposition would abound.