| 140 years ago, European arms traders established depots in Oman, Bahrain, Dubai, and elsewhere along the coast for gunrunning into Arabia, Mesopotamia, and Persia. However, the most lucrative market that emerged at the turn of the 20th century was the land bordering the Northwest Frontier Province of British India. |

Until the 1890s, the Frontier Tribes relied on jezails (matchlocks), knives and swords. The muzzle-loaders supplied to the Punjab Frontier Force did not provide the troops any significant advantage in mountain warfare. However, during the Jowaki Afridi Expedition of 1877-78, for the first time, the Tribes faced troops armed with rifles which were effective up to 500-600 meters with a maximum range of 1800-2000 meters. The early Sniders, followed by the Martini-Henry and the Lee-Metford rifle used smokeless ammunition and were capable of a vastly improved rate of fire.

The Frontier Tribes realised that the nature of combat had changed and they eagerly sought the new generations of rifles. This was evident in the Hunza-Nagar Expedition of 1891. During the attack on Nilt Fort, the Imperial Service Troops were opposed by an assortment of rifles—Berdan (Russian), Winchester (American) and Snider (British). It was also evident in the Chitral Campaign of 1895, when the tribesmen were qualitatively better armed than some of the Indian troops under siege as well as the Imperial Service Troops coming to their relief. There was evidence that arms were being smuggled from abroad but the issue was not investigated and the Frontier Tribes continued to acquire more breach loaders. During the hard-fought Malakand and Tirah Expeditions of 1897/1898, the British troops were engaged accurately at long ranges and suffered unprecedented casualties with 287 killed and 853 wounded. This was dramatic confirmation that the Frontier Tribes had acquired modern rifles in number, which compelled the Government of India to carry out a serious appraisal of the source of these weapons.

An exhaustive inquiry revealed that the Frontier Tribes possessed approximately 48,000 firearms of which 7,700 were ‘arms of precision’, 2500 were the older muzzleloaders gifted to allies that landed up with the tribes, 1,400 were lost or stolen from the Army (either from stores, sentries, or guardrooms), and a surprising 3,000 were constructed from materials obtained illicitly.

Wide-ranging measures were introduced to control the spread of arms and ammunition in the Frontier. The Arms Act was tightened and the issue of licenses reduced. The Army Regulations on the storage and handling of weapons and ammunition were made more stringent. Troops collected spent cases off the battlefield, scrapped weapons were crushed by mechanical steel hammers, railway police inspected luggage for smuggled arms and ammunition, and sentries were armed with inferior weapons to make them less attractive for theft.

The immediate effect was an increase in the price of arms and ammunition in the Tribal areas. By 1897, the local arms factories found it worth their while to manufacture complete homemade rifles instead of relying on more expensive parts of service weapons. The British made no effort to close down this cottage industry. It was better that the Pathans had inferior weapons of their own making than stealing British-made guns or parts—the most attractive being the bolt which was difficult to fabricate. However, with the tightening of sources of supply from within India, new actors entered the arena. During the Masud Blockade of 1902, a number of breech-loading rifles with ammunition appeared bearing mostly British but also Belgium and French markings.

When the Brussels Conference Act of 1890 ended the slave trade as well as the sales of guns to Africans, the arms trade shifted north from East Africa. European armies had converted to magazine-fed rifles with smokeless ammunition and large quantities of older weapons were available on the black market. Sixty percent of these weapons were landing on the Persian coast (to be smuggled to Afghanistan) some directly from Europe and some through Oman. They were largely handled by British traders based in Oman and Bahrain and one of the principal smugglers who moved the weapons through Persia was a Balochi Sardar with the title of ‘Martini Khan’.

To choke this arms trade, the British persuaded the Shah of Persia to confiscate illegal weapons and allow British ships to search vessels flying the Persian flag. Under pressure from the British as well as the Shah, the Sultan of Oman also allowed his dhows to be searched and illegal weapons confiscated. A consignment of 8,000 British rifles with 700,000 rounds of ammunition owned by a very active British firm, Francis, Times and Company, was intercepted. The British Navy continued to act in spite of the protests by many other British arms merchants, exporters, ship owners and manufacturers, and by 1899, the value of arms imported directly from Britain had dropped by 80 percent.

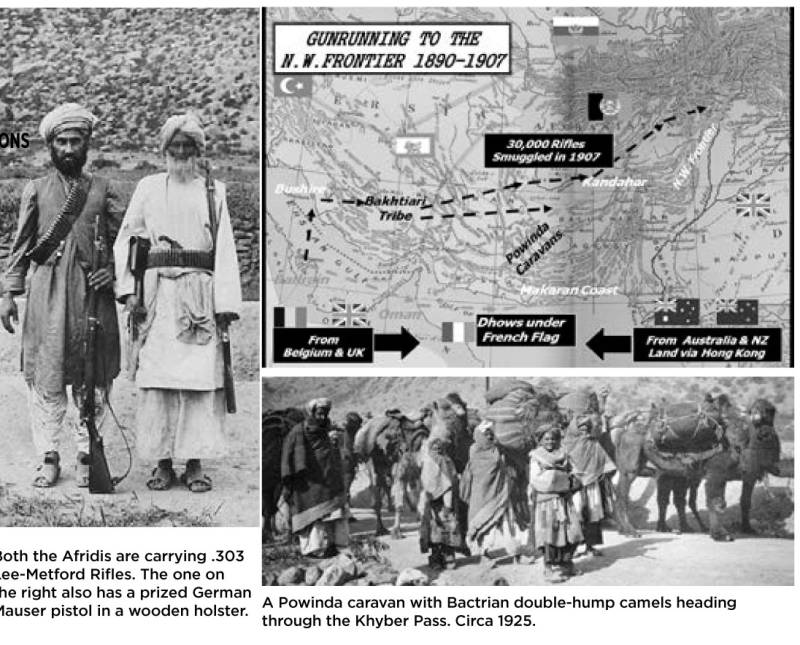

The trade was picked up by the French and in 1899, Monsieur Goguyer, arrived in Muscat with strong support from the French Government. Within 7-8 years, the French share of the arms trade rose to 50 percent with British traders down to 24 percent. In 1909 British Intelligence estimated that the French warehouses in Muscat contained over 100,000 arms and 10 million rounds of ammunition. The arms were arriving from all over e.g. in 1907 rifles appeared with markings of the Dominions of New South Wales and New Zealand. They sold a large number of obsolete rifles under the condition that they go back to England but the rifles found their way into the Persian Gulf through ships arriving from Hong Kong.

Under a joint declaration in 1862, the British and French had agreed to respect Oman’s independence and the Sultan of Muscat had signed a commercial treaty with France in 1844, which contained clauses of free trade. The French and British were political rivals and the British traders infiltrated weapons from Algeria into Morocco. Consequently, the French allowed dhows from Muscat to fly the French flag and under international law, the British Navy could not intercept them. Under an agreement between the British and the Shah of Persia, the smuggling of weapons to Afghanistan decreased but another route had opened up.

Dhows carrying arms and ammunition under the French flag were heading for the Makran Coast. They were commissioned by dealers in Muscat and received by Balochi Sardars who also provided intelligence to the Powinda caravans waiting 10-15 km behind the coast. The Powindas were ‘warrior-merchants’ and a wealthier branch of the powerful Ghilzai tribe based around Ghazni. Over 50,000 would travel to India in winter to barter merchandise from Central Asia but were not slow to seize the opportunity of entering a more profitable field of business and started directly purchasing arms from Muscat.

Resultantly, the market in Darra weapons collapsed but the enterprising Adam Khel Afridis now invested heavily in the trade with small parties going to Muscat via Karachi and returning through Afghanistan with rifles and ammunition. However, they did not know that the Government of India had decided to take several stern measures, the most significant being very close surveillance of Muscat by British cruisers combined with a blockade on the Makran coast. The British cruisers passed the information on the movement of dhows to the wireless station at Jask which rebroadcast it to small armed launches that intercepted the consignments in coastal waters of Makran. Along with this, the British conducted amphibious operations against the smuggler’s camps inland.

Consequently, the once totally reliable Arab dhows (called Na Khuda), now demanded a 100 percent deposit in advance to pay for the vessel in case it was captured or sunk. As the trade was becoming precarious, the Ghilzais demanded the money they had deposited in advance as payment for the guns should be returned but the dealers refused stating that they must take the value out in rifles. The dealers tried to establish depots at other sheikdoms along the coast but they were deterred by strict action and punishment by the British of the ruler of Dubai.

And then came the crash of 1910. With the blockade succeeding, there was a slump in the profits of European traders and their warehouses in Muscat closed down. Pathans returning from Makran reported that ships of ‘sirkar’ had put an end to trade. Money was in the hands of dealers and the Adam Khel gunrunners, who had speculated on the gun trade, lost heavily and faced financial ruin. This caused a minor crisis on the frontier during 1910. They started raiding the settled districts and demanded compensation for the losses suffered in what they regarded as legitimate trade. Workshops in Darra reopened but no one had the money to buy even a ‘pass-made’ weapon. Fortunately for the British, due to dissension within the factions, the Khyber Afridis (the most powerful branch of this tribe), hesitated to take the lead in raising an insurrection. The matter was handled tactfully but firmly and following the deliberations of a united Afridi Jirga held by Sir Ross-Keppel, one of the great captains of the Frontier, the issue was settled but with no compensation paid.

Further south, the furious Powindas invaded the Makran coast, threatening to cut the telegraph line linking Britain with India and driving the British outposts along the Mekarn Coast into the sea. Therefore, the Government of India landed a battalion between Chabahar and Jask supported by a mountain battery and a company of Sappers and Miners. In spite of the inhospitable terrain, the force made a rapid advance of 100 km to Bent and supported by very effective intelligence penetrated further inland. The Powindas scattered and having achieved its aim of ‘show of force’, the troops withdrew. The landings were repeated at a couple of more places and a small engagement with heavily armed gunrunners at Pushk.

The price of weapons on the Northwest Frontier increased and the local arms factories were back in business but the blockade and its effects came too late because the Frontier Tribes had amassed a large number of weapons and ammunition. Further, the trade through Muscat would be dwarfed by the spoils left by the Turkish and British Armies during the First World War.