I remember my seventh birthday in Changla Gali in 1956 when I was tossed up in a blanket and scared out of my wits. Changla was an insignificant little hamlet half way between Murree and Nathia Gali and at the highest point on the mountain range where the Galis are located. We were staying in the old Forest Rest House with a commanding view of Murree and the dim and distant lights of Rawalpindi were barely visible at night. Since then I have remained a regular visitor to the hill stations of Murree and the Gali. However, as the number of visitors to what has been described as the Switzerland of Pakistan became a flood, there has been a relentless assault on its fragile ecology by the uncontrolled construction.

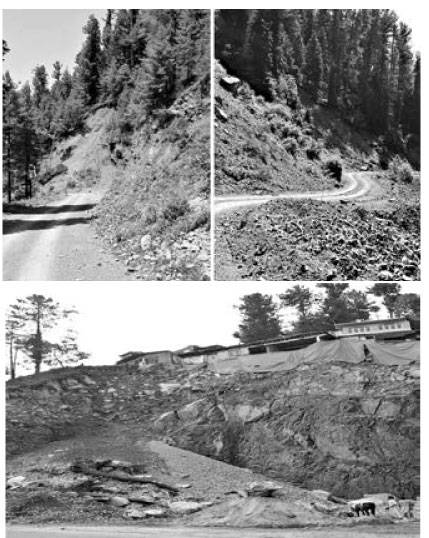

It begins right from the moment one accesses the expressway from Islamabad. Lush green hills clad in scrub and trees of wild olives, laburnum, karanda and kachnaar, have been scraped away on both sides of the road and replaced by eyesores, the biggest being the Bahria Township. Taking cue from this, other smaller housing schemes are mushrooming on the hill sides. The same eyesores emerge as one closes up to Murree. Obviously the local administration does not have the will to check this mushrooming growth. Who does this land belong to? I am told that much of this land was either of the Forest Department that has been encroached on or ‘Shamlat’ land that has been sold off by the locals. Shamlat in essence was land provided to communities (villages) for farming or raising livestock. It was not meant for commercial use per se and certainly not to be sold off for housing colonies. If the communities are not using this land for the purpose it was intended, then it should revert back to the State. Presently it seems locals are claiming entire hillsides and mountains. It is painful to see the beauty of the green mountains of my childhood disappearing at an ever increasing pace.

In the 10 km drive from Kuldana till Barian, there are only two stretches where the forest is surprisingly still virgin. That is because most of it is cantonment land. The rest is hotels, apartments and shops shoulder to shoulder and all crowding what has now become a narrow road. The vistas of the Pir Panjal Range that were visible as one drove along this stretch are now masked by ribbon construction which is the bane of every road in Pakistan. The Highway Ordinance of 1959 stipulates the Right of Way (ROW) i.e. the distance from the edge of the road till where no construction is permitted but it is not enforced. If construction is not checked it will be a nightmare to drive along the main road with cars parked all over. At the height of the season there is a queue of cars a kilometre long, struggling to get through the small market of Barian. There is a relief from construction for the next 6-7 kilometres till the turning off for Ayubia where the Forest Department seems to have enforced their rights, and then it starts off again, intermittently but certainly expanding nearly till Dunga Gali. The Switzerland of Pakistan is surely dying!

The 2003 building bylaws of the Galiyat Development Authority (GDA) extend only 250 feet on both sides of the main roads from Abbottabad to Barian and Thandiani, the Kohala Road and the Nathiagali-Bakot Road. By implication, neither the major population residing within the Galiyat region are subject to any building laws nor are the hotels, houses and multi-storied apartments mushrooming up along the smaller roads that now form a network and often approach the same villages from two different directions. A reader who has driven past Murree and onto Nathia may think that I am exaggerating about high-rise buildings. However, the next time he drives up he should stop and look over the edge at these hotels. What seems like a one or two story building on the edge of the road invariably has 6-8 floors going 300 feet down and hugging the steep mountainside. According to the seismic zoning map of Pakistan, the Galiyat lie on the edge of Zone 4, which is the highest seismic zone but the GDA has not laid down any building code for earthquake resistant structures. I shudder to imagine the devastation that would occur to life and property if the area was hit by a 7.6 magnitude earthquake similar to what struck areas of Azad Kashmir in 2005 and which the Galiyat narrowly escaped. Over 15 years have passed and the amount of construction has increased tenfold. As this article was going into print, a video clip was circulating showing a hotel in Nathia Gali sliding down the hill side and overturning.

The ecological disaster that is developing is a complex problem that requires a detailed study and plan spread over 10-15 years. Some immediate measures must be enforced to arrest the decay. For example, the construction of hotels along the main arteries must cease and the building bylaws of the GDA should be revamped to encompass the entire area. In the mid-term, enclaves should be developed in un-forested areas for hotels and restaurants with arrangements for processing garbage and effluents. The hotels existing along the roads should be relocated to these enclaves in the next 4-5 years by providing incentives. Irrespective of the source of funding, construction/expansion of byroads should be controlled by one authority and the Forest Department should have the final say.

The bottom line is that there must be a will to check the decay and restore the beauty and charm of the Galis. This article can only help in creating awareness. To create the will needs a concentrated drive by the public and private sector based on a masterplan and the required funding to restore the beauty of the Galiyat.

Monday, November 18, 2024

Our Switzerland is dying

Major General Syed Ali Hamid

Punjab schools set to reopen tomorrow as smog eases

4:19 PM | November 18, 2024

Bangladeshi court seeks probe report against ex-premier Hasina by Dec 17

4:06 PM | November 18, 2024

Jorge Martin wins 2024 MotoGP championship

4:00 PM | November 18, 2024

UN chief urges G20 nations to lead global efforts for peace, climate action

3:59 PM | November 18, 2024

UK seeks ‘pragmatic’ ties with China at G20 summit in Brazil

3:58 PM | November 18, 2024

-

Pakistan’s judiciary champions climate justice at COP29 in Baku

-

Pakistan’s judiciary champions climate justice at COP29 in Baku

-

Punjab struggles with persistent smog as Met Office forecast rainfall

-

Punjab residents face escalating smog crisis as pollution levels soar across country

-

Qatar says Hamas 'no longer welcome' in Gulf state

-

Allama Iqbal's birth anniversary being observed today

Agricultural Alarm

November 17, 2024

Cost of Inaction

November 17, 2024

Navigating Global Blocs

November 17, 2024

Tightening Screws

November 16, 2024

EV Policy

November 16, 2024

Establishment of New Schools and Colleges in I-14 Sectors

November 17, 2024

Seasonal Price Fluctuation

November 17, 2024

Climate Literacy: A National Need

November 17, 2024

Let’s Rush to Save the Earth

November 17, 2024

Internet Woes Impacting Pakistan’s Freelancers

November 16, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024