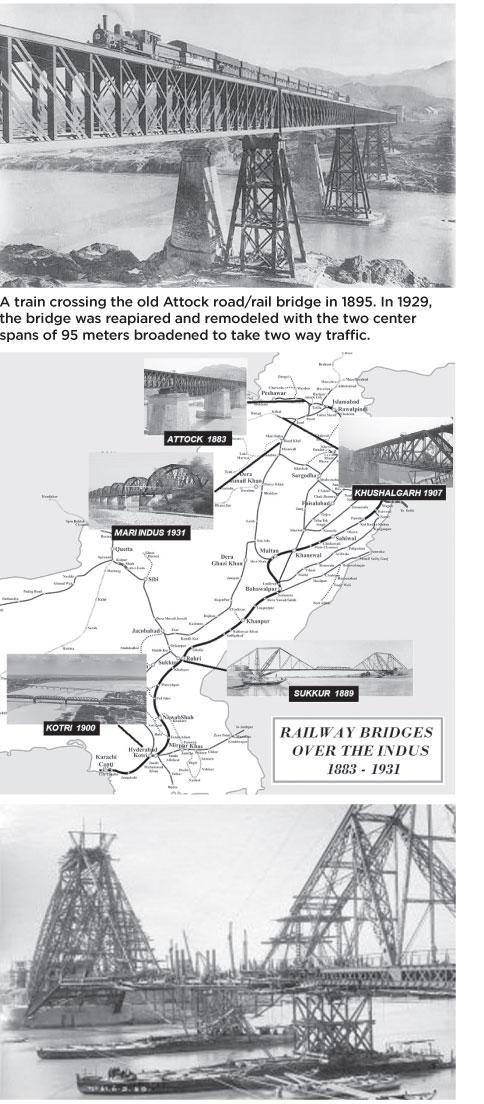

On the way to Peshawar along the Grand Trunk Road, if you take a left after crossing the concrete bridge over the River Indus as Begum ki Sarai, two kilometres onwards, you will be rewarded by a magnificent view of a 460-meter-long steel road/rail bridge that is supported on three massive masonry and stone pillars. The Attock Bridge as it is known is just one, and the most impressive of five bridges that the British constructed over the Indus in less than 50 years.

The development of a railway network in north-western India began in 1855 with three lines, the Scinde, Punjab and Delhi Railways. Unlike the tracks extending from Bombay and Calcutta which had commercial worth, the ones in the northwest were for strategic purposes. Over the next 25 years, the network spread up from Karachi towards Sukkur and northwest from Delhi towards Lahore and the logistic base of the British India Army at Rawalpindi. It also extended down from Lahore towards Multan and Bahawalpur. By 1878, the railways had bridged the five rivers of the Punjab: the bridge over the Beas (1869), the bridge over the Ravi at Jassar and Lahore, the Alexandra Bridge over the Chenab at Gujrat (1875), the mile long bridge over the Jhelum (1876), the bridges over the Sutlej at Phillaur (1870) and the Empress Bridge at Bahawalpur (1878). However, the formidable barrier of the River Indus now lay ahead. With their earlier experience, engineers were aware that bridging rivers at open sites where the course was not confined between rocky hills was more difficult. Therefore, the early road/rail bridges across the Indus were constructed at Attock, Sukkur and Khushalgarh where the river was confined.

From the time that the East India Company annexed Punjab in 1849, replacing the bridge of boats on the Indus at Attock with a permanent solution was under serious consideration and in 1860 work commenced on building a 7.3-meter-wide and 2½ km long tunnel. However, due to leakages, machinery breakdown and cost overruns, the project was abandoned when only 78 meters remained between the two ends of the boring. The Second Afghan War gave an impetus to extend the railway line till Peshawar and by 1879, the line from Rawalpindi had arrived at Attock on the southern side of the Indus. A year later it had also been laid from the other bank onwards till Peshawar but the construction of the bridge remained.

When the Indus arrives at the Attock Gorge it has already traversed 1,500 km, draining an area of 310,800 sq km and during floods, it could rise over 20 meters or more. In fact, in 1841, when a glacial dam across the Shyok River burst, the river rose 30 meters at Attock and washed away a Sikh Army camped upstream on the Plains of Charch. Therefore, the engineers selected a site that would give the rail/road bridge headroom of 30 meters above the low water level. The bridge was to be constructed in five steel spans with the two of 95 meters being the longest in India at that time. The main challenge was laying the foundation of the only pier that was in the river channel that had to rest on a rocky shoal. Working in the fast-flowing icy cold water, it took a year for a cofferdam to be constructed and when the water was pumped out, the condition of the rock that was revealed at the bottom was alarming. It was badly honeycombed and deeply fissured—highly unsuitable for a pier foundation. But time was short and the girders and trestles had already arrived from Britain. The area inside the cofferdam was filled with concrete and work commenced on erecting the pier.

The piers were not like the ones we see supporting the Attock Bridge today i.e. huge structures of masonry and concrete. Good building stone at the site was scarce and instead, trestles of riveted wrought iron (like pylons) were constructed which were considered better at withstanding earthquakes. The working speed was enviable with all four trestle piers erected in as many months. The erection of the timber staging and the spans on top of them were completed within six months during the winter of 1882-83 though time was lost due to bad weather. Work had to stop when rain and winds numbed the hands and feet of the laborers. Shortly after its completion, a massive earthquake displaced the girders on the trestles by an inch but there was no damage and in May 1883, the first locomotive passed over the bridge.

The entire construction was carried out with no pneumatic tools or electric drives. Kipling who visited the Kaiser-i-Hind Bridge at Ferozepur during its construction four years later in 1887, describes a scene that could resemble Dante’s inferno and would have been similar to the Attock or any other iron and steel bridges that spanned the rivers in India. “A few hundred workers are hard at riveting. The clamour is startling, even a hundred yards away from the bridge; but standing at the mouth of the huge iron-plated tunnel, it is absolutely deafening. The flooring quivers beneath the hammer-stroke; the roof of the corrugated iron nearly half an inch thick which will form the floor of the cart road, casts back the tumult redoubled: and it bounds and rebounds against the lattice-work at the side. Riveters …..work like devils; and the very look of their toil, even in the bright sunshine, is devilish. Pale flames from the fires for the red hot rivets, spurt out from all parts of the black ironwork where men hang and cluster like bees; while in the darker corners, the fires throw up luridly the half-nude figures of the riveters as they bend above the fire-pots, or, crouching on the slung support, send the rivets home with a jet of red hot sparks from under the hammer-head.

The first Attock Bridge lasted well for nearly 40 years, but by 1921, the spans had become distorted and girders were seriously over-stressed. While the management was considering options, trains were restricted to a speed of 8 kph on the bridge and heavy road traffic was not permitted when a train was crossing overhead. The most expensive option was to construct an entirely new bridge downstream with a central span measuring a huge 200 meters. Finally, after four years of deliberation, it was decided to entirely replace the two 95 meters spans and strengthen the three 80 meters spans with the structure supported by concrete and masonry piers. However, when the bedrock of the pier in the water channel was exposed for a second time, the engineers again had a shock. For 3 meters on the downstream side, the island had been eroded like a bad tooth and half of the trestle was resting on an overhang of a decaying rock. The railways were extremely fortunate that it had survived for so many years.

Therefore, an entirely new foundation was constructed with concrete reinforced with tons of rail pieces to support the massive 17,000-ton concrete and masonry pier that encased the old trestle and was designed to take a double railway track. The steelwork for the two 95 meters spans had arrived before the end of November 1928. The British resident engineer on site was ably assisted by two bridge inspectors, Sardar Sahib Prem Singh and Karam Elahi, whose skill in bridge-building would become famous throughout northern India. Sikh and Muslim, these two brilliant inspectors, barely able to read and write in English, carried through to the successful completion of one of the greatest bridge reconstruction works ever taken in India. With their respective gangs working in friendly rivalry from the two ends of the bridge, in under four months the spans were completed and all the erection gear was dismantled and sent away. During the next Monsoon Season, there were two massive floods in the Indus. The first again due to the bursting of a glacial dam on the Shyok River and the second in which a flood in the Indus, combined with heavy rains in the catchment areas of the River Kabul and the Haro. If the damage to the foundation of the river pier had not been detected and repaired in time, most certainly the mighty Attock Bridge would have been washed away.

The development of a railway network in north-western India began in 1855 with three lines, the Scinde, Punjab and Delhi Railways. Unlike the tracks extending from Bombay and Calcutta which had commercial worth, the ones in the northwest were for strategic purposes. Over the next 25 years, the network spread up from Karachi towards Sukkur and northwest from Delhi towards Lahore and the logistic base of the British India Army at Rawalpindi. It also extended down from Lahore towards Multan and Bahawalpur. By 1878, the railways had bridged the five rivers of the Punjab: the bridge over the Beas (1869), the bridge over the Ravi at Jassar and Lahore, the Alexandra Bridge over the Chenab at Gujrat (1875), the mile long bridge over the Jhelum (1876), the bridges over the Sutlej at Phillaur (1870) and the Empress Bridge at Bahawalpur (1878). However, the formidable barrier of the River Indus now lay ahead. With their earlier experience, engineers were aware that bridging rivers at open sites where the course was not confined between rocky hills was more difficult. Therefore, the early road/rail bridges across the Indus were constructed at Attock, Sukkur and Khushalgarh where the river was confined.

From the time that the East India Company annexed Punjab in 1849, replacing the bridge of boats on the Indus at Attock with a permanent solution was under serious consideration and in 1860 work commenced on building a 7.3-meter-wide and 2½ km long tunnel. However, due to leakages, machinery breakdown and cost overruns, the project was abandoned when only 78 meters remained between the two ends of the boring. The Second Afghan War gave an impetus to extend the railway line till Peshawar and by 1879, the line from Rawalpindi had arrived at Attock on the southern side of the Indus. A year later it had also been laid from the other bank onwards till Peshawar but the construction of the bridge remained.

When the Indus arrives at the Attock Gorge it has already traversed 1,500 km, draining an area of 310,800 sq km and during floods, it could rise over 20 meters or more. In fact, in 1841, when a glacial dam across the Shyok River burst, the river rose 30 meters at Attock and washed away a Sikh Army camped upstream on the Plains of Charch. Therefore, the engineers selected a site that would give the rail/road bridge headroom of 30 meters above the low water level. The bridge was to be constructed in five steel spans with the two of 95 meters being the longest in India at that time. The main challenge was laying the foundation of the only pier that was in the river channel that had to rest on a rocky shoal. Working in the fast-flowing icy cold water, it took a year for a cofferdam to be constructed and when the water was pumped out, the condition of the rock that was revealed at the bottom was alarming. It was badly honeycombed and deeply fissured—highly unsuitable for a pier foundation. But time was short and the girders and trestles had already arrived from Britain. The area inside the cofferdam was filled with concrete and work commenced on erecting the pier.

The piers were not like the ones we see supporting the Attock Bridge today i.e. huge structures of masonry and concrete. Good building stone at the site was scarce and instead, trestles of riveted wrought iron (like pylons) were constructed which were considered better at withstanding earthquakes. The working speed was enviable with all four trestle piers erected in as many months. The erection of the timber staging and the spans on top of them were completed within six months during the winter of 1882-83 though time was lost due to bad weather. Work had to stop when rain and winds numbed the hands and feet of the laborers. Shortly after its completion, a massive earthquake displaced the girders on the trestles by an inch but there was no damage and in May 1883, the first locomotive passed over the bridge.

The entire construction was carried out with no pneumatic tools or electric drives. Kipling who visited the Kaiser-i-Hind Bridge at Ferozepur during its construction four years later in 1887, describes a scene that could resemble Dante’s inferno and would have been similar to the Attock or any other iron and steel bridges that spanned the rivers in India. “A few hundred workers are hard at riveting. The clamour is startling, even a hundred yards away from the bridge; but standing at the mouth of the huge iron-plated tunnel, it is absolutely deafening. The flooring quivers beneath the hammer-stroke; the roof of the corrugated iron nearly half an inch thick which will form the floor of the cart road, casts back the tumult redoubled: and it bounds and rebounds against the lattice-work at the side. Riveters …..work like devils; and the very look of their toil, even in the bright sunshine, is devilish. Pale flames from the fires for the red hot rivets, spurt out from all parts of the black ironwork where men hang and cluster like bees; while in the darker corners, the fires throw up luridly the half-nude figures of the riveters as they bend above the fire-pots, or, crouching on the slung support, send the rivets home with a jet of red hot sparks from under the hammer-head.

The first Attock Bridge lasted well for nearly 40 years, but by 1921, the spans had become distorted and girders were seriously over-stressed. While the management was considering options, trains were restricted to a speed of 8 kph on the bridge and heavy road traffic was not permitted when a train was crossing overhead. The most expensive option was to construct an entirely new bridge downstream with a central span measuring a huge 200 meters. Finally, after four years of deliberation, it was decided to entirely replace the two 95 meters spans and strengthen the three 80 meters spans with the structure supported by concrete and masonry piers. However, when the bedrock of the pier in the water channel was exposed for a second time, the engineers again had a shock. For 3 meters on the downstream side, the island had been eroded like a bad tooth and half of the trestle was resting on an overhang of a decaying rock. The railways were extremely fortunate that it had survived for so many years.

Therefore, an entirely new foundation was constructed with concrete reinforced with tons of rail pieces to support the massive 17,000-ton concrete and masonry pier that encased the old trestle and was designed to take a double railway track. The steelwork for the two 95 meters spans had arrived before the end of November 1928. The British resident engineer on site was ably assisted by two bridge inspectors, Sardar Sahib Prem Singh and Karam Elahi, whose skill in bridge-building would become famous throughout northern India. Sikh and Muslim, these two brilliant inspectors, barely able to read and write in English, carried through to the successful completion of one of the greatest bridge reconstruction works ever taken in India. With their respective gangs working in friendly rivalry from the two ends of the bridge, in under four months the spans were completed and all the erection gear was dismantled and sent away. During the next Monsoon Season, there were two massive floods in the Indus. The first again due to the bursting of a glacial dam on the Shyok River and the second in which a flood in the Indus, combined with heavy rains in the catchment areas of the River Kabul and the Haro. If the damage to the foundation of the river pier had not been detected and repaired in time, most certainly the mighty Attock Bridge would have been washed away.