STOCKHOLM-“No one would choose this, it’s obvious,” said Anders who has unwanted sexual thoughts about children.

He is at the forefront of a unique scientific study underway in Sweden to see if drugs can prevent paedophiles from acting on their urges.

Anders, who agreed to be interviewed using a pseudonym, says he has never abused children but sought help because he knew his sexual fantasies were “not normal”. He hopes the ground-breaking trial will halt his “improper” urges.

At Stockholm’s Karolinska Institute, patients like Anders who have sought help for paedophile fantasies, but have not acted on them, are being given a drug normally used to treat advanced prostate cancer to determine if it reduces the risk of them sexually abusing a child.

“The goal is to establish a preventive treatment programme for men with paedophiliac disorder that is both effective and tolerable so that we can prevent child sexual abuse from happening in the first place,” psychiatrist and lead researcher Christoffer Rahm told AFP.

Various types of chemical castration are used around the world on paedophiles convicted of actual sex offences, but the treatment is not used preventively. “What we introduce with this study is a way of shifting perspective from being reactive to proactive,” Rahm said.

Clinical studies on paedophiles are also rare, because of ethical issues and difficulties gathering data. Conducting research where patients risk harming a third party requires special cooperation with legal and child welfare experts, Rahm said.

In the clinical trial, half of the 60 subjects receive an injection of the drug Degarelix and the other half get a “dummy” drug, or placebo.

Subjects who receive Degarelix will have non-detectable levels of testosterone after three days, an effect that lasts about three months.

Testosterone is involved in several of the most important risk factors for committing child sex abuse, including high sexual arousal, diminished self-control and low empathy, Rahm said.

Anders does not know if he has received the real drug or the placebo, and will only find out when the study is completed in two to three years.

“I have noticed that my sex drive has been sinking lately but I don’t know if it’s attributable to the medicine,” Anders says.

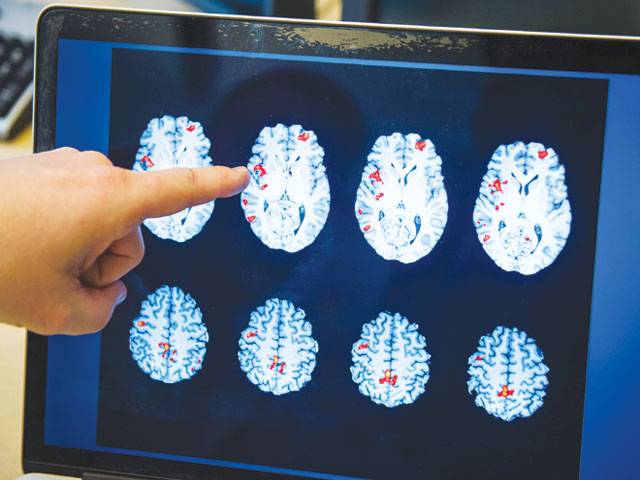

Subjects will also undergo brain scans using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) while they are looking at computer-generated pictures of partially-clothed people of all ages, to see how different areas of their brains react.

“We’re trying to establish objective markers to determine the risk of the patient actually committing child sexual abuse,” brain scan expert Benny Liberg said.

He described the three regions that were activated on Anders’ brain scan during the experiment: that responsible for controlling sensory perception; the region that monitors one’s own body; and that which inhibits unwanted behaviour responses.

“This is the type of behaviour we’re very much trying to affect with the pharmaceutical intervention,” Liberg said.

Using the drugs together with the brain scans and patient counselling, Rahm and Liberg hope they have devised a formula that will enable scientists to accurately assess the risk of a patient sexually abusing a child. But the drug alone will not be a miracle cure.

During the three-month period with low testosterone levels, “you can start up more long-term treatments, such as social interventions and psychotherapy,” Rahm said.

Volunteers for the study have been recruited from Karolinska University Hospital’s treatment programme for unwanted sexual behaviour, and from a national helpline.

Child sex assaults are devastating for the victims, and with as many as 85 percent of such crimes going unreported, tools are needed to treat potential abusers, said Stefan Arver, the head of Karolinska Institute’s Centre for Andrology and Sexual Medicine.

He estimates that about five percent of the population “entertain thoughts and fantasies involving children in a sexual context,” though very few ever act on them.

Around 80 percent of those who seek treatment in Stockholm were exposed to physical or psychological trauma in childhood.

Anders started having his unwanted thoughts when he was 15 and he said it took a long time to muster the courage to get help.

“I realised almost two years ago that I needed to take care of this in some way. But there’s such a stigma, you’re afraid of being reported,” he said.

“The stigma prevents people from seeking help, which could be destructive in the long term.”