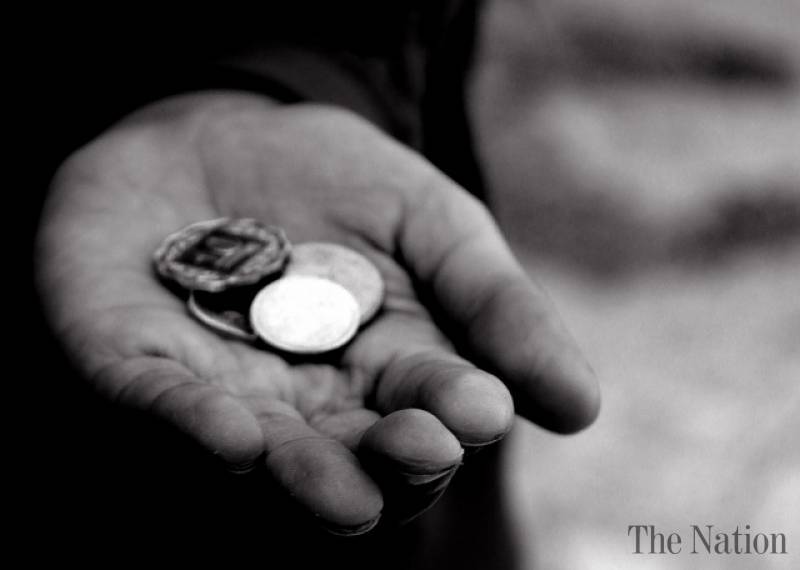

Beggary is a vocation, the roots of which go a long way back in time. Historically, begging for alms stems from poverty and want, but it has of late, developed into a mafia controlled source of revenue. I had a brief glimpse of this while shopping in a busy commercial complex of Lahore. Two female beggars walked into the shop and to everyone’s amazement produced hundreds of coins wrapped in dirty pieces of cloth in exchange for banknotes.

Driving across the Federal Capital, one was apt to see a good looking young woman dressed in blue denim trousers and shirt, with a scarf over her head. What caught one’s attention was a smart cloth bag often used by university students, slung over one shoulder and two or three books clutched in one hand. This con artist would walk across to cars waiting for the traffic light to turn green and spin a ‘tear jerker’ about how she was an impoverished orphaned student with a passion for continuing her education, but had no money to pay her college fee. When questioned she would talk about a sick mother and a brood of younger siblings in a voice choked with emotion and eyes brimming with tears. One day she disappeared from her accustomed spot, until weeks later, while driving on the main Gulberg Boulevard in Lahore, I stopped at the Main Market signal to find her walking from car to car repeating her lines. As she approached my window, I asked her if she had changed her universities. I got a scathing look as she simply ‘skipped’ my car and continued her performance down the line.

Driving along the Jinnah Avenue with my family, I often saw a tall, emaciated man selling newspapers and shivering uncontrollably in the freezing weather. We felt sorry for the individual as he did not appear to possess any warm clothes and during our next ‘drive by’ gave him a couple of thick brand new sweaters. A few days later, we found him at another spot in exactly the same state as before. On an impulse, I pulled over to the side and strolled across to him. He probably recognised me and briskly made his escape. I never saw him at his designated point of business after this, although I thought I had caught a glimpse of him at a busy Rawalpindi intersection some days later, doing his ‘thing’.

One day my son came home ‘feeling good’ because he had bought a pedestal fan for a young lad, who had approached his car during a particularly severe Pindi summer and spun a tale of woe about how his invalid father and sick mother were living in a small room that turned into an oven during the hot weather. Days later, the same young lad once again approach my son at another intersection and failing to recognise him, spun the same story word to word ending it with an appeal for a pedestal fan. When my son reminded him that just a few days earlier, a fan had been given to him, the lad disappeared into the traffic in a flash.

Then there was the blind middle aged man, who entered our home in Lahore many decades ago guided by a young apprentice, but surprised everyone when he legged it down the drive and out of the gate unaided on being challenged by our German Shepherd, who had somehow got loose. Needless to say, we never saw the man or his sidekick in the vicinity again.

Giving charity is an act which is favourable in the eyes of God, but doling out money to professional beggars is an act that proliferates, what has now become an ‘industry’. I would rather give my share to organisations, who will spend it well. By doing this I will at least have the satisfaction of knowing that my humble contribution has been well utilised.