Adam B Ellick

I had the privilege of following Malala Yousafzai, on and off, for six months in 2009, documenting some of the most critical days of her life for a two-part documentary. We filmed her final school day before the Taliban closed down her school in Swat Valley; the summer when war displaced and separated her family; the day she pleaded with President Obama’s special representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan, Richard Holbrooke, to intervene; and the uncertain afternoon she returned to discover the fate of her home, school and her two pet chickens.

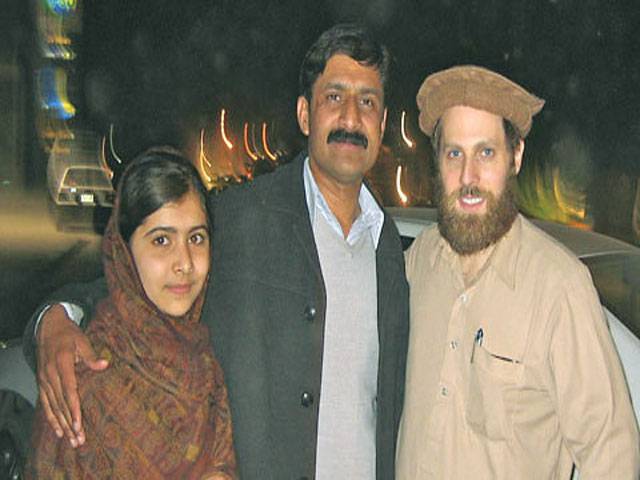

A year after my two-part documentary on her family was finished, Malala and her father, Ziauddin, had become my friends. They stayed with me in Islamabad. Malala inherited my old Apple laptop. Once, we went shopping together for English-language books and DVDs. When Malala opted for some trashy American sitcoms, I was forced to remind myself that this girl - who had never shuddered at beheaded corpses, public floggings, and death threats directed at her father - was still just a kid.

Today, she is a teenager, fighting for her life after being gunned down by the Taliban for doing what girls do all over the world: going to school.

The Malala I know transformed with age from an obedient, rather shy 11-year-old into a publicly fearless teenager consumed with taking her activism to new heights. Her father’s personal crusade to restore female education seemed contagious. He is a poet, a school owner and an unflinching educational activist. Ziauddin is truly one of most inspiring and loving people I’ve ever met, and my heart aches for him today. He adores his two sons, but he often referred to Malala as something entirely special. When he sent the boys to bed, Malala was permitted to sit with us as we talked about life and politics deep into the night.

After the film was seen, Malala became even more emboldened. She hosted foreign diplomats in Swat, held news conferences on peace and education, and as a result, won a host of peace awards. Her best work, however, was that she kept going to school.

In the documentary, and on the surface, Malala comes across as a steady, calming force, undeterred by anxiety or risk. She is mature beyond her years. She never displayed a mood swing and never complained about my laborious and redundant interviews.

But don’t be fooled by her gentle demeanor and soft voice. Malala is also fantastically stubborn and feisty - traits that I hope will enable her recovery. When we struggled to secure a dial-up connection for her laptop, her Luddite father scurried over to offer his advice. She didn’t roll an eye or bark back. Instead, she diplomatically told her father that she, not he, was the person to solve the problem — an uncommon act that defies Pakistani familial tradition. As he walked away, she offered me a smirk of confidence.

Another day, Ziauddin forgot Malala’s birthday, and the nonconfrontational daughter couldn’t hold it in. She ridiculed her father in a text message and forced him to apologise and to buy everyone a round of ice cream - which always made her really happy.

Her father was a bit traditional, and as a result, I was unable to interact with her mother. I used to chide Ziauddin about these restrictions, especially in front of Malala. Her father would laugh dismissively and joke that Malala should not be listening. Malala beamed as I pressed her father to treat his wife as an equal. Sometimes I felt like her de facto uncle. I could tell her father the things she couldn’t.

I first met Malala in January 2009, just 10 days before the Taliban planned to close down her girls’ school, and hundreds of others in the Swat Valley. It was too dangerous to travel to Swat, so we met in a dingy guesthouse on the outskirts of Peshawar, the same city where she is today fighting for her life in a military hospital.

In 10 days, her father would lose the family business, and Malala would lose her fifth-grade education. I was there to assess the risks of reporting on this issue. With the help of a Pakistani journalist, I started interviewing Ziauddin. My anxiety rose with each of his answers. Militants controlled the checkpoints. They murdered anyone who dissented, often leaving beheaded corpses on the main square. Swat was too dangerous for a documentary.

I then solicited Malala’s opinion. Irfan Ashraf, a Pakistani journalist who was assisting my reporting and who knew the family, translated the conversation. This went on for about 10 minutes until I noticed, from her body language, that Malala understood my questions in English.

“Do you speak English?” I asked her.

“Yes, of course,” she said in perfect English. “I was just saying there is a fear in my heart that the Taliban are going to close my school.”

I was enamored by Malala’s presence ever since that sentence. But Swat was still too risky. For the first time in my career, I was in the awkward position of trying to convince a source, Ziauddin, that the story was not worth the risk. But Ziauddin fairly argued that he was already a public activist in Swat, prominent in the local press, and that if the Taliban wanted to kill him or his family, they would do so anyway. He said he was willing to die for the cause. But I never asked Malala if she was willing to die as well.

Finally, my favourite memory of Malala is the only time I was with her without her father. It’s the scene at the end of the film, when she is exploring her decrepit classroom, which the military had turned into a bunker after they had pushed the Taliban out of the valley. I asked her to give me a tour of the ruins of the school. The scene seems written or staged. But all I did was press record and this 11-year-old girl spoke eloquently from the heart.

She noticed how the soldiers drilled a lookout hole into the wall of her classroom, scribbling on the wall with a yellow highlighter, “This is Pakistan.”

Malala looked at the marking and said: “Look! This is Pakistan. Taliban destroyed us.”

In her latest e-mail to me, in all caps, she wrote, “I WANT AN ACCESS TO THE WORLD OF KNOWLEDGE.” And she signed it, “YOUR SMALL VIDEO STAR.”

I too wanted her to access the broader world, so during one of my final nights in Pakistan, I took a long midnight walk with her father and spoke to him frankly about options for Malala’s education. I was less concerned with her safety as the Pakistani military had, in large part, won the war against the Taliban. We talked about her potential to thrive on a global level, and I suggested a few steps toward securing scholarships for elite boarding schools in Pakistan, or even in the United States. Her father beamed with pride, but added: “In a few years. She isn’t ready yet.”

I don’t think he was ready to let her go. And who can blame him for that?

Adam B Ellick is a correspondent of The New York Times.

Saturday, November 23, 2024

My ‘small video star’ fights for her life

No sit-Ins or gatherings allowed in Islamabad: Naqvi

10:20 PM | November 22, 2024

Govt scheme to provide Rs 1.24bn airfare relief for pilgrims

8:53 PM | November 22, 2024

UN says 2024 'deadliest year on record' for humanitarian aid workers with 281 deaths globally so far

8:46 PM | November 22, 2024

Metro bus service to remain closed on Nov 24 ahead of PTI protest

8:10 PM | November 22, 2024

-

Lahore tops global pollution rankings as smog worsens, AQI reaches hazardous levels

-

Lahore tops global pollution rankings as smog worsens, AQI reaches hazardous levels

-

Hunger crisis to increase in South Sudan, warns UN

-

Pakistan’s judiciary champions climate justice at COP29 in Baku

-

Punjab struggles with persistent smog as Met Office forecast rainfall

-

Punjab residents face escalating smog crisis as pollution levels soar across country

UN Crossroads

November 22, 2024

Smog Trade-off

November 22, 2024

Undersiege Again

November 22, 2024

Land of Vigilantes

November 21, 2024

United in Genocide

November 21, 2024

Proposal to counter increasing cases of harassment

November 22, 2024

Critique of RFE/RL’s Coverage of the SCO Summit

November 22, 2024

Real vs Reel

November 22, 2024

Independent Supreme Court

November 21, 2024

Fat Loss Fantasy

November 21, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024