Gordon Corera

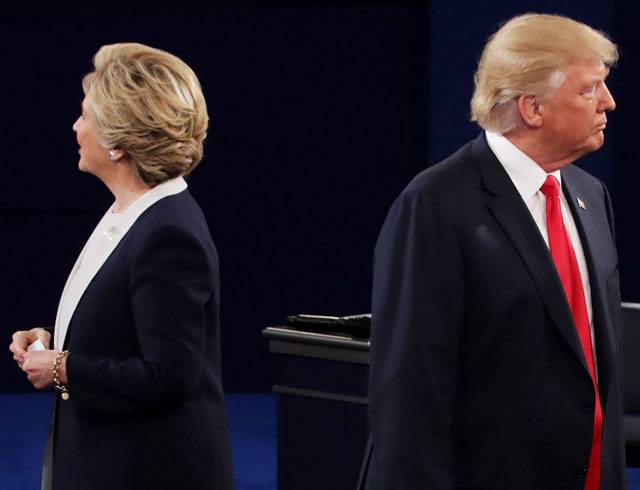

Amidst all the heat of the presidential debate on Sunday night, hackers surfaced for a brief moment.

The two candidates clashed over a claim that hackers tied to the Russian state were trying to influence the election.

Two days earlier, on Friday, the US director of national intelligence had pointed the finger at the highest levels of the Russian state for intrusions. Critics of Russia have argued that any role would be part of a growing trend of not just stealing information but also weaponising it.

The story begins in May, when the Democratic National Committee (DNC) became concerned about suspicious behaviour on its computer network. It called in the security firm CrowdStrike to take a look.

Two hacker groups were found on the system, one that had just entered and another that had been there for nearly a year.

“We recognised that there was an adversary in their environment that had targeted that network and was looking at communications…. and research on opposition candidates,” Shawn Henry, chief security officer at Crowdstrike and a former executive assistant director of the FBI, tells the BBC.

“We did attribution back to the Russian government.

“In this particular case we believed it was the Russian government involved in an espionage campaign - essentially collecting intelligence against candidates for the US presidency.”

Aggressive attacks

But after the DNC and Crowdstrike went public in pointing the finger, material was released into the public domain, shifting the focus from traditional espionage - theft of data - to something more like an influence operation designed to have an impact in the real world.

This is part of a wider trend of Russian activity that Western officials have been watching with alarm for some time.

“We are seeing a more open and aggressive use of cyber, so that the information becomes a weapon and a weapon of influence,” Sir David Omand, a former director of Britain’s GCHQ, tells the BBC.

On Friday, the US director of national intelligence went public over these concerns. “These thefts and disclosures are intended to interfere with the US election process,” James Clapper said in a joint statement with the Secretary of the Department of Homeland Security.

“Such activity is not new to Moscow - the Russians have used similar tactics and techniques across Europe and Eurasia, for example, to influence public opinion there. “We believe, based on the scope and sensitivity of these efforts, that only Russia’s most senior officials could have authorised these activities.” The Kremlin has rejected the accusations, describing them as “nonsense”.

Scan and probe

One additional concern is that information might be manipulated before it is leaked.

In other words, false information could be planted amongst a dump of real data which will be picked up and reported on before people have a chance to verify it.

A number of US states have also reported scanning and probing of election related systems - such as voter databases. US intelligence said this may have originated from servers operated by a Russian company but it said it was not in a position to attribute this activity to the Russian government.

It also said that it would be difficult for anyone to actually alter ballot counts because of the decentralised nature of the system and protections in place.

But even the attempt and the possibility of intrusion may be enough to cause problems when it comes to public perception around election time.

“The only reason I can see why you would want to do that is to sow doubt about the outcome of the election,” Sir David Omand says of the activity.

“Because if you are in a district where you have to rely on the voting machines and you know the voting machines [and] the database has been penetrated can you really trust the result?

“You will very quickly get rumours after the election that the result in some areas could be in doubt. “I can see plausible reasons why - at the moment - Russia would be quite happy to see the United States inconvenienced in that way.”

Cyber-arms race

Russia has pioneered techniques of hybrid warfare and information operations in recent years including in conflicts in Ukraine and Georgia.

Russian intelligence also has a long history of “active measures” and “influence operations” going back to the Cold War. But cyberspace offers a new means for pursuing this agenda and on a transformative scale.

With discussion about how the US should respond, the trend worries some experts. “At the nation state level there needs to be diplomatic discussion about what is acceptable and what is not,” argues Mr Henry. “Or we will see an increasing arms race in this space. “And that doesn’t work out for anybody.”–BBC