"Just as it is preposterous for a German Jew to accept collective responsibility for Nazi atrocities, it is preposterous that I should think of myself as sharing integrated collective responsibility within a group that denies my capacity to judge for myself.”

Legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin wrote this in his paper Equality, Democracy and Constitution: We The People in Court, published in Alberta Law Review (1990) wherein he tried to elucidate three core principles of democracy: participation, stake and independence.

Genuine participation necessitates both horizontal and vertical equality of citizens in the political system. The former implies absolute equality of rights, and the latter, equal individual influence over the governance hierarchy. Participation isn’t ensured by mere universal suffrage – even though in some parts of Pakistan we’re still fighting for women’s right to vote.

Equal stakes would require homogenous causal reciprocation between the state’s power and an individual’s rights. Ahmadis who voted for the PPP in 1970 cannot be held responsible, as a part of a collective Pakistani community, for the Second Amendment in 1974 that excommunicated them. For, the very bill taking away the group’s fundamental right to self-identify had minimised the Ahmadis’ stake in Pakistan.

There is no independence if the state (legally) dictates what its citizens should think, thereby curtailing freedom of conscience, speech and religion. All curbs on independence, which eventually metamorphose into breaches of stake and participation, are usually implemented for ‘interests of larger society’.

While state institutions safeguarding societal interests is a noble endeavour, it is when ‘larger society’ is deemed synonymous with numerical majority that the flimsy line between democracy and majoritarianism is contravened. After all, is there a greater interest for any society than ensuring uncompromising equality?

As we approach a decade of sustained democracy – at least as a front – it is understandable, even if naïve, to consider democracy itself as the objective. While “democracy is the best revenge” has echoed as an indomitable chant of resistance, the right of the citizens to elect their leaders to counter the autocracy of the men in uniform has been the dubbed the collective goal of the masses.

But democracy, a system of governance, isn’t an end in itself. After millennia of deliberation, democracy has been deemed by many as the best means to achieve an end, which is at the very least founded upon – if not entirely constituted of – absolute equality.

Democracy as ‘what the majority want’ has been sold to fuel majoritarianism, creating paradoxical totalitarian democracies. There has been no better simultaneous manifestation of this than the populist surge around the world that has given us Erdogan, Modi and Trump, in addition to the right-wing surge across Europe as we speak.

The state’s will being considered the same as the individual’s – the crux of Jean-Jacque Rousseau’s “General Will”, originally designed for smaller homogenous states – isn’t workable in the modern heterogeneous world.

Unlike many other states, Pakistan was born with multiculturalism. And two recent developments highlight how majoritarianism continues to be sold as democracy in the country that is diverse in ethnicities and beliefs.

The FATA-KP merger, which has been given the green signal by the Reforms Committee, has practically hinged on one main contention since the Gen (Retd.) Naseerullah Babar led committee first gave it a shot in the lead up to the 1977 elections. That is the assertion that Riwaj (tribal customs) is incompatible with Pakistan’s judicial process, and that any legal system sans the age-old jirga, is against the ‘will of the people’ in FATA.

The fact that the Frontier Crimes Regulation (1901), which upheld clauses like ‘collective responsibility' – wherein family or tribe members could be punished for an individual’s crimes – was sustained for over a century, owing to ‘collective will’ of its victims, is one of the most brutal legal ironies of modern times.

And yet the proposed reforms only replace FCR with the Riwaj Act. This would mean FATA continuing to have the jirga – the most literal manifestation of institutional misogyny anywhere in the world – as per the uncodified Riwaj.

How can the ‘will of the tribal people’ – a contentious claim on its own considering the backlash – be used to uphold a parallel justice system that subordinates, often violently, one half of the population?

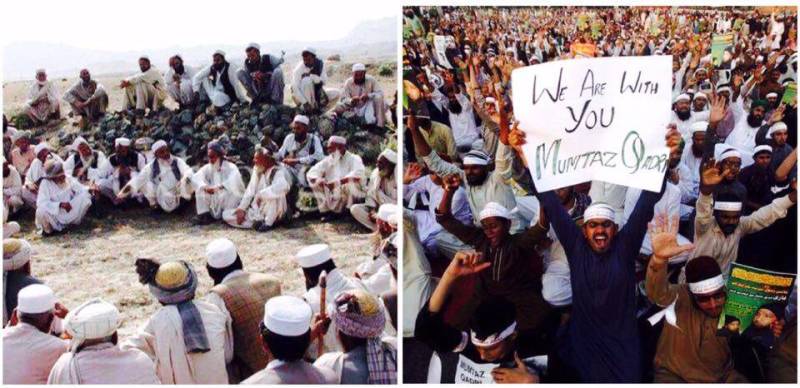

The ongoing state action against ‘social media blasphemers’ is another blatant exhibit of majoritarianism. For, no similar action is being taken against those who blaspheme against any religions, and ideologies, except Islam. It is the legal – and logical – corollary of the Pakistan Penal Code’s Sections 295-B and 295-C, also known as the blasphemy laws, which uphold death punishment for sacrilege against Islam alone.

This shows that the action against alleged blasphemers isn’t being taken on any principle. If that were the case, the clampdown would target insults to other religions, which are ubiquitous and have never required the safety net of social media anonymity. As reiterated in the Islamabad High Court, and the Interior Ministry, the crackdown is to ‘safeguard the sentiments of Muslims’.

Not only does this verdict paint a communal urgency on the entire Muslim community by slashing its pluralism and refusing to acknowledge that many aren’t offended by any form of ‘blasphemy’ against Islam, it also contradicts Article 20 of the Constitution, which guarantees freedom of religion.

But when the Constitution contradicts itself in many places, often to uphold exclusive rights for the most intolerant brand of Islam, it’s not surprising to see state institutions upholding similar majoritarian principles using the pretext of democracy.

Even if any manifestation of the most outrageous idea collectively offends the sensibilities of 97% of the population, those offended sentiments cannot be used to shackle an individual’s freedom of conscience, the very foundation of electoral equality.

Similarly, even if every single tribeswoman ‘willed’ that her right to vote be taken away, a democratic government cannot uphold that will, no matter how many tribesmen deem it offensive to their traditions.

Any popular move that breaches the rights of a section of the society cannot he upheld as democratic, solely on the basis of the numerical strength backing it. For democracy is a process to ensure equality, not a gauge to measure statistical clout.