I was born at 12 Lawrence Road Lahore. It was a humongous albeit dilapidated pre partitioned colonial bungalow which was allotted to my uncle following their migration to the newly formed state of Pakistan. 12 Lawrence Road soon after became a refugee camp for the rest of the family, close or distant, migrating to this side of the line. 20 years later, I was born in the same very house. My childhood days as well as my early youth spent on Lawrence road. My uncle motivated, rather inculcated into me the habit of running, which to date, I do with great enthusiasm. Daily, early morning he used to wake me up and I used to run 6 kilometers on Lawrence road before setting off to school. I have fond memories of Lawrence road which never waned away. Even now when I visit this road, life comes to a grinding halt. During the winter afternoons I, with my father after his office, would saunter around aimlessly, discussing history mostly –or sit on one of the benches in the Lawrence Gardens listening to the hoarse owls’ dirges or watching the huge web-winged bats take airy rounds before flying back to their abodes to silently cling in their clusters.

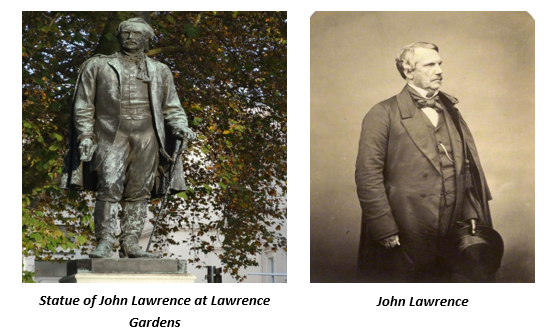

I loved the names Lawrence road or Lawrence gardens which sounded so ‘at home’ though the same were changed to Majid Nizami Road and Jinnah Bagh. I remember asking my father as to who was this Lawrence after whom the road and the gardens were named. He had told me that he was the first pioneer Chief Commissioner of Punjab, who later rose to become the Viceroy of India (1864-1869). He was infamous for his role in 1857. “So, the man actually resided and worked here in some form, good or bad, but his infamy in 1857 became the cause to get his name expunged. What happened to Lyallpur? One of the first originally planned cities within British India. Why the city’s name was changed to Faisalabad? Did King Faisal ever work here” I would bicker only to see that smirk on his face in his usual manner.

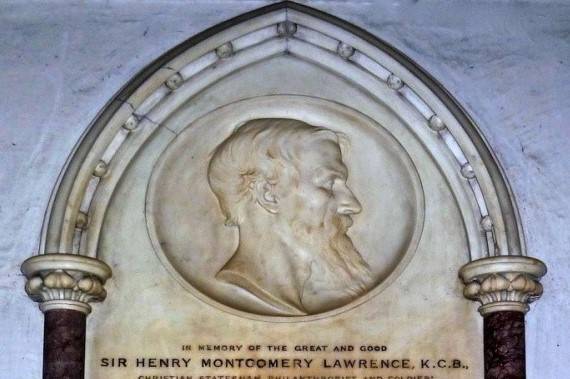

Cricket ground and Quaid-e-Azam Library at Lawrence Gardens

After independence, as with other innumerable roads and places in Lahore, the names of Lawrence road and Lawrence Gardens were also changed. Nevertheless, as with the rest of the case, the two are still known by their original names. There are sporadically - though rare, are examples where the original names were retained either willingly or owing to huge resentment from the inhabitants such as Jacobabad, Abbottabad etc. The retention or rejection therefore owed its existence historically on that invisible yet indelible mark left behind on the memories of people by that particular man – whether in a positive or negative sense.

The story I am now going to narrate would prove that in the case of Lawrence Road and Lawrence Gardens, there still exists a reason as to why the original name should not be restored.

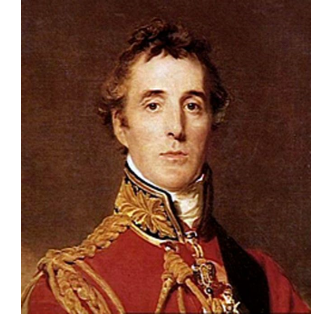

While we all know John Lawrence, the first Chief Commissioner of Punjab and later the Viceroy of India on whose name the Lawrence Road and the Lawrence Gardens spanning over an area of 172 acres in Lahore stand, few know that John had an elder brother too. Sir Henry Lawrence was an artillery officer and a Brigadier General in the Company’s army. Sir Henry and his younger brother John Lawrence entered the civil service of Punjab in Lahore together and worked for four years of what could be described as the ‘joint rulers of Punjab’. Both had the energies, spirit and vigour to work and excel. Yet despite being brothers, their joint stint as absolute rulers was fraught with perpetual personal discord, friction and strife. Their mutual acrimony and bitterness saw no limits. The younger brother John was so rancorous towards his elder brother that he even resented the very sight of him and his abhorrence towards him never abated.

Following the victory at Gujrat, on the 30th of March 1849 the annexation of the Punjab to the dominion of East India Company was proclaimed. In order to govern the newly acquired territory Lord Dalhousie, the British Governor General constituted a Board of Administration comprising three members; Brigadier General Henry Lawrence, the British Resident at Lahore was named President and entrusted with matters connected with defence and relations with Sardars while his younger brother, John was put in charge of land settlement. Charles Grenville Mansel (Later replaced by Robert Montgomery) was entrusted with the administration of Justice. The Board was placed directly under the control of the Governor General.

Soon the working of the Board started to suffer badly owing to ever widening spasm between the two brothers. While John was primarily a desk-chained nerd who tired his eyes wearied his brain in his dull and stuffy office den weaving policies after policies draining the very blood of the inhabitants, his elder brother despised office work, was always on move reaching far flung locations and like a ‘physician’ trying to placate the pain inflicted by his younger brother. In their mutual disputes Lord Dalhousie openly sided with the former. The conflict came to an impasse when both brothers put in their resignation at the beginning of 1853.

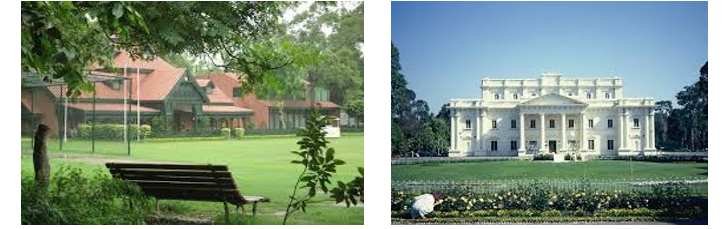

The story of the two brothers will not be complete without understanding the character and personality of Lord Dalhousie, the then Governor General of India and who was to play a vital role in the John’s ascendency to the pinnacle of East India Company.

Lord Dalhousie (1812 – 1860) was a Scot; critics regard him as a highly mean and ambitious man from the beginning. Born with the proverbial silver spoon in the mouth, he was the son of Governor General of Canada. He attended Harrow and Oxford with above average grades. His appetite for power and position got uncaged while he was barely 23. In 1835 he made the first attempt to enter the Parliament (House of Lords) but was unsuccessful. This jolted him greatly. In 1837, at 25 he made a second attempt and was successful. By 1841 he was considered for the position of Governor of Madras which he thought to be too small a sphere [“------”] there is no other young man in the House of Lords of my standing at all, “out of sight out of mind” is more speedily made true in London and politics than anywhere else. If I go to Madras, who at the end of five years when I return will know my name?

Lord Dalhousie Governor General/Viceroy

(1848-1856)

He prodded well his connection with the young Queen (Victoria) and ultimately managed to become the President of the Board of Trade which simultaneously won him a seat in the cabinet. He worked efficiently and made a name in railways. Though, later he was offered chairmanship of the railway commission but declined calling it a “fish bait” that too “a badly dressed fly.”

Later, the government as well as the Prime Minister (John Russel) convinced him to agree to go out to India as Governor General.

Lord Dalhousie is the most negatively remembered personality in the Raj. It was always said that policies of Lord Dalhousie led paved path for the Indian revolution of 1857 which shacked the roots of East India Company in India and consequently transfer of the power in the British crown.

While handing over charge of his office to Lord Dalhousie, his predecessor the outgoing Lord Hardinge had remarked that [“----”] so far as human foresight could predict, it would not be necessary to fire a gun in India for seven years to come. Similarly, the English press had written ‘everything seems to favour the new ruler; India is in full enjoyment of peace, which humanly speaking, there seems nothing to disturb.’ Events however, were destined speedily to falsify these predictions: the seven years Lord Hardinge had predicted ultimately proved to be seven years of war. As a matter of fact he was from the very beginning determined to extend direct British rule over as large an area as possible. He declared that [“---”] the extinction of all native states of India is just a question of time.

The chief instrument through which Lord Dalhousie implemented his policy of annexation was the ‘Doctrine of Lapse.’ As per this, when the ruler of a protected state died without a natural heir, his/her state was not to pass to an adopted heir, but to be annexed to the British dominions. Many states were annexed by applying this doctrine. This was however, was not the case with either Punjab or Oudh. In the case of Oudh, Lord Dalhousie hit upon the idea of alleviating the plight of the people of Oudh. The State was annexed in 1856. In reality, it was the immense potential of Oudh as market for Manchester goods which excited Dalhousie’s greed and aroused his ‘philanthropic’ feelings. From Lord Dalhousie’s landing in Calcutta in Jan 1848 until he laid his high office eight years later on the whirlwind he himself had sown his continuous policy was, in his own words “to seize all rightful opportunities of acquiring territory” (to earn more and more revenue); and in the process not unwilling to create such “rightful opportunities”.

Coming back to the Lawrence brothers in Lahore; it was the younger brother John Lawrence in whom he found the perfect pair. Both were ambitious, self-serving and lacked empathy. In John he found an ideal machine willing to draft policies after policies extracting money in the name of revenue and taxes. While the Anglo-Sikh war still in progress he had frankly notified his intentions to Henry (then resident of Punjab) to draft the proclamation of annexation of Punjab which was to be issued as soon as the Khalsa had been finally overthrown. Henry remained lackadaisical owing to his sympathies, and conscious of the causes which had driven the Sikhs to take up arms. Henry with equal promptitude sent him his resignation. Lord Dalhousie with his artful deceit and cunning cajoled him to withdraw his resignation. In fact he knew well that Henry was so vital for him, to the point of being indispensable, for until the wounds caused by the war had been healed, he dared not remove the good ‘physician’ in whom alone the Sikhs had confidence.

While John was overstraining himself drafting policies and papers hitting the people in the gut, Henry was proving himself a beneficent providence to the complaining Punjabis. He was a man with a heart of crystal whose men loved him immensely. As President of the Board, Henry travelled extensively in the province, each year travelling three to four months, each day riding thirty to forty miles. At each station, he would visit public offices, jails, bazaars receive visitors of all ranks, inspect the Punjab Regiments and Police and receive daily petitions sometimes numbering in hundreds. In his diary he noted that under his administration, they had raised five Regiments of fine cavalry and infantry, six regiments of very good military police, planted thousands of trees, ensured ‘serais’ were ever present on main roads, police posts every two to three miles and steps were taken in education. During his tours and based on his assessments, he would write his analyses and recommendations to Lord Dalhousie as well as to his brother. But all this was neither fair to Lord Dalhousie nor to his brother John.

As a result, tension between the two brothers got so tense that the efficiency of the administration began to suffer. Lord Dalhousie, in order to ease the tension between the brothers appointed Robert Montgomery (vice Mansel), who was the life friend of both brothers. The brothers now made their new coadjutor a sort of umpire between them, and he being of a ‘business type’ more often sided with John than with Henry. As their mutual opposition only hardened – each immune to compromise, the affairs of the state came to a standstill. The two then agreed to refer their differences to Lord Dalhousie, each pleading that as they could no longer work together amicably, be transferred elsewhere. Naturally, the Governor General decided in favour of the man of business, not of the man of heart. The Board of Administration was abolished, Henry Lawrence was relegated to Rajputana, and John, his brother was left at Lahore to reign alone as Chief Commissioner of the Punjab. The decision deeply hurt Henry, who thought he had proved his self by understanding the issues of Punjab and its people in threadbare. Dalhousie explained his decision by stating that after some years of military administration in the Punjab, there was now a need for a civil administration to which John Lawrence was more suited.

According to the local populace Henry was sacrificed because of the greatness of his love for them and to resist inhuman, unrealistic money minting policies of his younger brother on the behest of Lord Dalhousie. According to some; because of the jealous ambitions of the younger brother. Henry Lawrence departed, literally amidst peoples’ lamentation. He had filled his sheet, writing all in letters of gold. Thus, faded away the noblest Englishman who had ever set foot in India.

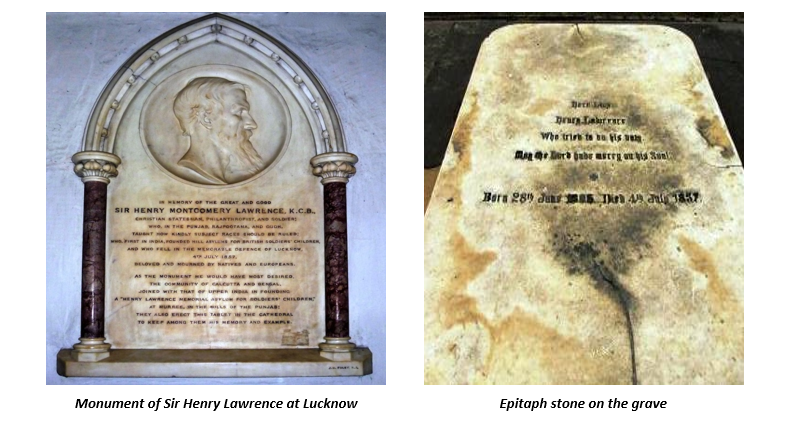

Post Script: In May 1857 two months after assuming his post in Oudh, the Indian rebellion of 1857 commenced. Henry arranged for a garrison in Lucknow of 1700 men and took refuge in the British residency. On the morning of 30th June despite being weak and exhausted with illness, he led a march to anticipate some mutinous regiments approaching Lucknow. Around six to seven miles from Lucknow he encountered 15000 soldiers. Being outnumbered, Lawrence retreated to the residency. During the siege of Lucknow, on second July a shell burst in his quarters and shattered his thigh. He succumbed to his injuries after three days. When Lawrence was critically injured he is supposed to have said to those around him: “Put on my tomb only this; Here lies Henry Lawrence who tried to do his duty.” This epitaph appears on his tombstone at the Residency graveyard.