The 1950s were exciting times for mountaineers. The Second World War had ended and after tension had subsided on the ceasefire line in Kashmir, Pakistan opened its mountains to international mountaineering expeditions. One of the early ones was a German-Austrian Expedition that came in 1953. Prior to Independence, Srinagar used to be the logistic base for expeditions to the Karakorum and Nanga Parbat but it was now the small military garrison town of Rawalpindi. I would accompany my father to meet these expeditions and I remember the lawns of Flashman Hotel piled with crates of climbing equipment, oxygen bottles, tents and tinned food. Nylon was not yet in use and I recollect running the fine silk ropes through my fingers and liking the feel and texture.

Nanga Parbat (locally known as Diamer), is the ninth highest mountain in the world situated at the termination of the northern outcrop of the Indian continental crust. It stands 8,126 meters (26,660 feet) tall and is the western anchor of the Himalayan massif around which the Indus River takes a wide swing before it enters the plains of Pakistan. It is actually an extinct volcano that toppled onto its side and presented a mystery to geologists because it is rising at a faster rate than the other mountains in the region. Computer simulations ultimately revealed that Nanga Parbat was losing its mass faster due to higher degree of erosion. The cause of this higher erosion was that it is the only peak in the entire region which catches both the Monsoon from the east in summer and the Westerly rains in winter.

Nanga Parbat has a tremendous vertical relief over local terrain in all directions and presents dramatic views, whether you see it from a flight to Gilgit or from the ground. On its southern side, it has the highest mountain face in the world: The Rupal Face which rises 4,600 meters (15,090 feet) above its base. Writing in the 1930s, the author and civil servant E.R. Eddison narrates, “I remember, years later, his describing to me the effect of the sudden view you get of Nanga Parbat from one of those Kashmir valleys; you have been riding for hours among quiet richly wooded scenery, winding up along the side of some kind of gorge, with nothing very big to look at, just lush, leafy, pussy-cat country of steep hillsides and waterfalls; then suddenly you come round a corner where the view opens up the valley, and you are almost struck senseless by the blinding splendour of that vast face of ice-hung precipices and soaring ridges, sixteen thousand feet from top to toe, filling a whole quarter of the heavens at a distance of, I suppose, only a dozen miles.”

When the scramble to climb 8000 meters peaks began in the 1930s, European nations had an unwritten agreement to share them—K2 became an Italian mountain, Everest was British and Nanga Parbat was a German preserve. A famous mountaineer said, ‘You don’t conquer a mountain. It allows you to reach its summit,’ and Nanga Parbat has been notoriously reluctant in permitting climbers to claim its peak. After a German-American expedition failed in the first attempt in 1932, Nanga Parbat turned into a prestige object of the Nazi regime who declared it as the ‘German mountain of destiny.’ The next attempt was led by Willi Merkel two years later with the full backing of the Nazi government. It reached a height of 7,900 meters (25,900 feet) but was trapped in a snowstorm. During the desperate retreat, the team lost three climbers (including the leader) and six Sherpas. Till then, this disaster, “for sheer protracted agony, has no parallel in climbing annals.” A third attempt in 1937 followed the same route as Merkel’s expeditions but an avalanche struck Camp IV and seven Germans and nine Sherpas (almost the entire team) were killed. The perpetual defeats on Nanga Parbat became part of German political and cultural discourse during the Nazi period and the early days of the Federal Republic. By the fourth attempt, this time by a German-Austrian team in 1953, 31 climbers, mostly Germans) had perished on Nanga Parbat which earned it the ghastly title of ‘Killer Mountain’.

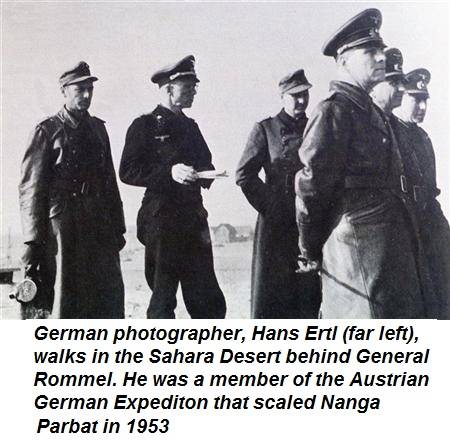

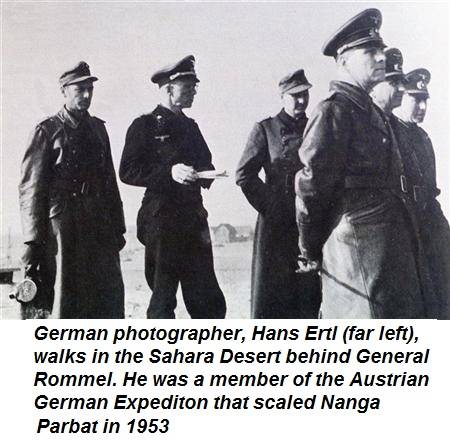

The 1953 attempt was led by Karl Herrligkoffer whose half-brother Willi Merkel had perished on Nanga Parbat. It was Willi’s death that propelled Herrligkoffer—a doctor but not a climber—into initiating the 1953 expedition. The climbing leader was Aschenbrenner who was one of the survivors of the 1937 Expedition, and the photographer was Hans Ertl. Hans was a cameraman during the Nazi era, and worked on several propaganda films directed by the well-known Leni Riefenstahl. During the Second World War he accompanied General Rommel in North Africa and many of the famous photos of the Desert Fox were taken by Hans who earned the reputation of being ‘Rommel’s photographer’.

The expedition approached the mountain along the same route taken by earlier German expeditions and faced a difficult ascent. The weather remained bad and the route beneath the avalanche-prone Rakhiot Wall to gain the East Ridge was extremely long (18 km). Five Sherpas from India, who were to join the expedition had been turned back at the frontier in Kashmir and were substituted by four porters from Hunza. In spite of their inexperience, Ali Madad, Haji Beg and Hidayat Khan worked hard to keep the higher camps supplied but a fourth porter—Amir Mehdi—was unable to make the ascent because no crampons large enough for his boots were available. The final push for the summit was dramatic. For various reasons Herman Buhl made the final ascent alone. He set out at 2.30 am without oxygen, facing 1200 meters of ascent with a horizontal traverse of over 6 ½ kilometers. Troubled by sleep, the Austrian climber managed to struggle on, propped up by two tablets of methamphetamine (aka crystal meth or speed). It was widely used as a stimulant by German troops during the Second World War to stave off fatigue, hunger and sleep deprivation.

Buhl reached the summit at 7pm, which was dangerously late. On the way back, night set in and he had to bivouac standing on a narrow ledge, with his ski sticks in one hand, and grabbing onto a small hold with the other. He dozed occasionally but managed to retain his balance and was fortunate that it was a calm night with no wind-chill. Emaciated and hallucinating from exhaustion but propped up with more pills, he headed down to Camp V the next morning, without a crampon or his ice axe, which he inadvertently left on the summit. While Buhl was struggling alone, the expedition was working to fill the vacuum below and put into place a rescue. Walter Frauenberger arrived at Camp V and was joined by Hans Ertl and three of the Hunza porters carrying oxygen. Since it was too late in the day to set off to search for Buhl, the group at Camp V conducted a short ceremony in memory of those who had died in 1934 and put up a memorial. Frauenberger was adding the finishing touches when he spotted a dot descending and was overcome by emotions. “I was laughing and crying at the same time as I hurried to finish my chiselling, constantly glancing upwards.” Buhl reached Camp V at 7 pm, 24 hours after reaching the summit and over 40 hours after setting out. Nothing like this amount of ground had ever been covered in a day before, at such altitude.

Buhl was the first to conquer an 8000-meter peak alone. He made the ascent without oxygen and was very lucky to survive with only a few frostbitten toes. The story of his ascent on Nanga Parbat reflects his style of climbing; totally focused and by taking enormous risks succeeding where others failed. Four years later on Broad Peak, he and his companions proved that without any help from high altitude porters, a small team could climb an 8,000 meter peak. But it was Buhl’s last summit. Some days later, while attempting Chogolisa (7,668 meters), he fell through a cornice to his death. His body was never recovered and remains buried within the mountains he loved.

“The mountains are silent teachers, and they teach us noble qualities: humility in the face of nature, modesty, courage, privation, and strength of will”—Hermann Buhl. A 1986 film named ‘The Climb’, covers the story of Hermann Buhl’s ascent on Nanga Parbat.

When the expedition arrived back at Rawalpindi, the Pakistan Army hosted a reception in their honour on July 18, 1953. It was organised on the apron of the small Chaklala Airport and attended by senior army officers including Lieutenant General Nasir Ali Khan and Maj Gen Syed Shahid Hamid. The accompanying photos of the reception are from Shahid Hamid’s collection but since all the faces of the members of the expedition are sunburnt and supporting beards, it is difficult to identify Buhl or the others. In the group picture taken during the reception, the climber on the right is one of the porters from Hunza.

Postscript. Amir Mehdi, the Hunza porter who remained at the base camp because there were no crampons large enough for his boots could not be held back the next year when he accompanied the Italian Expedition that ascended K2 (8,611 meters). He climbed till 511 meters below the summit, but unlike the other climbers he hadn’t been given proper high-altitude snow boots. As a result, he lost all his toes to frostbite and spent eight months in hospital recovering from the ordeal. However along with Walter Bonatti he set a record of spending the night in an open bivouac at 8,100 meters (26,578 feet). It was broken 24 years later in 1978 by Jim Wickwire, the first American to summit K2, who survived an overnight solo bivouac at 8,200 meters (26,900 feet).

Tuesday, November 19, 2024

Conquering the killer mountain

Major General Syed Ali Hamid

Youth-led solutions highlighted at Climate Change Workshop in Lahore

9:07 PM | November 18, 2024

Areeba Habib advocates for tolerance after facing backlash over Diwali celebration

9:06 PM | November 18, 2024

Islamabad enforces section 144 ahead of PTI's Nov 24 protest

8:55 PM | November 18, 2024

Imran Khan calls for massive rally on Nov 24 to reclaim freedom: Aleema Khan

8:42 PM | November 18, 2024

Zulfi Bukhari, Shahbaz Gill, Murad Saeed, Hammad Azhar declared absconders by ATC

8:30 PM | November 18, 2024

-

Pakistan’s judiciary champions climate justice at COP29 in Baku

-

Pakistan’s judiciary champions climate justice at COP29 in Baku

-

Punjab struggles with persistent smog as Met Office forecast rainfall

-

Punjab residents face escalating smog crisis as pollution levels soar across country

-

Qatar says Hamas 'no longer welcome' in Gulf state

-

Allama Iqbal's birth anniversary being observed today

Stability in Sight

November 18, 2024

Police Accountability

November 18, 2024

Digital Disconnect

November 18, 2024

Agricultural Alarm

November 17, 2024

Cost of Inaction

November 17, 2024

The Law of Nations

November 18, 2024

Living in a Haze

November 18, 2024

The Impact of Graphic Content

November 18, 2024

Beating the Bush

November 18, 2024

Amazon Fire Incident

November 18, 2024

ePaper - Nawaiwaqt

Nawaiwaqt Group | Copyright © 2024