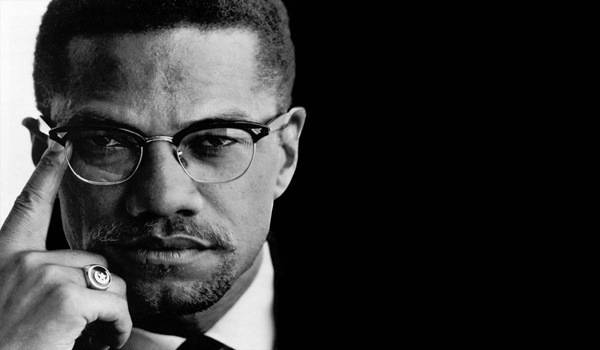

Malcolm X in one of his speeches proclaimed that ‘You are not to be so blind with Patriotism that you can’t face reality. Wrong is wrong, no matter who does it or says it.’ Nationalism projects around the world promote a particular myth about the origin and history of that state, deviating from which could make you a ‘traitor’ in the state’s eye. The degree to which one can deviate from the ‘party line’ varies and the state’s response depends on the country in question. In postcolonial states in particular, questioning the authenticity of Nationalist version of history is still a taboo and invites the ire of authorities rapidly.

During the last few months, a debate has raged in India following the suicide of a Dalit student at Hyderabad Central University. A few months before this tragic incident, the University had suspended Rohith Vemula’s research grant since he was found ‘raising issues under the banner of Ambedkar Students Association’. Soon after the suspension, he faced the ire of Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP)—the student wing of Hindu nationalist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)—for protesting against the death penalty for Yakub Memon. ABVP’s members physically attacked him in his room and he had to be taken to a hospital for treatment afterwards. Rohith Vemula, in his suicide note, wrote that ‘The value of a man was reduced to his immediate identity and nearest possibility. To a vote. To a number. To a Thing. Never was a man treated as a mind.’

In February 2016, left-wing students from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) held a protest at their campus against the capital punishment sentence awarded to Afzal Guru, despite protests by ABVP members. Due to ‘anti-India’ slogans raised at the event, sedition charges were brought against Kanhaiya Kumar, President of JNU’s student union and Umar Khalid, prominent member of Democratic Student Union. Upon his release from jail on an interim bail, Umar Khalid addressed JNU students. Among other things, he mentioned that the government had to use a law instituted in 1860 to put him in jail, an irony that Hindu Nationalists used a law made by the British. Kanhaiya Kumar made a similar speech upon his return from jail and expressed faith in India’s constitution and democracy. Both the students have been branded ‘anti-national’ by Indian media; Kanhaiya has since been attacked physically and by the media repeatedly.

I fail to understand how the grand edifice of Indian nationalism, erected by luminaries such as Nehru and Gandhi, is threatened by a few protesting students in Hyderabad and Delhi. It is perhaps the ultimate failure of the Indian nationalism project that it cannot accommodate dissenting voices, despite the fact that India is a diverse country with more than a billion inhabitants. The fault-lines in this project including the Caste question, issue of ‘territories’ such as Kashmir and Manipur, gender disparity and religious intolerance need to be addressed by the proponents of ‘Shining India’. Why has it become so easy in the subcontinent to brand people ‘traitors’ at the drop of a hat? Did we achieve freedom from the British in order to subjugate our own people? Will the ‘unwashed’ masses of subcontinent ever get a chance to raise their voice against the status quo? Why have we changed the definition of democracy from ‘power shared by people’ to ‘rule of the majority’?

Doug Stanhope, an American author, once wrote that ‘Nationalism does nothing but teach you to hate people you have never met, to take pride in accomplishments you had no part in.’ Pakistan has seen its fair share of ‘Anti-Nationals’ over the years. The suppression of opposing voices started soon after partition. The ‘Babrra massacre’ in August 1948 has been erased out of our collective memory. Insurgency in Balochistan has been going on since April 1948, albeit in five different phases. Language riots in the former East Pakistan also started in 1948. Bengalis, Baloch and Khudai Khidmatgar didn’t conform to the desired singularity in Pakistani nationalism and were brutally punished for it. Students belonging to the Democratic Students Federation (DSF) in the early 50s or National Students Federation (NSF) in later years faced exactly the same circumstances that Kanhaiya Kumar and Umar Khalid are facing today. In the 1980s, Pakistani students faced the state’s wrath for questioning the state narrative. Asma Jahangir, I.A Rehman, Dr Mubarak Ali, Sabeen Mahmood and various other have been punished in various ways by the state because they challenged the state narrative.

Nationalism is raising its ugly head in different parts of the world right now. In Turkey, the President has almost declared himself the epitome of Turkish Nationalism and criticising him is akin to questioning the basis of nationalism. In France, you are no longer considered French—even if you were born and raised there—if your forefathers came from former French colonies or if you want to wear a headscarf. In the United States, you can get thrashed by security detail of Donald Trump if you oppose his ideas about American nationalism. In Israel, questioning the policies of state or even the ‘settlers’ can land you in trouble. In China, students cannot even google what happened in ‘Tiananmen Square’ during 1989 on the internet, or ‘The Cowsheds’ (University Professors in China were subjected to ‘re-education’ in Maoist philosophy during the ‘Cultural Revolution’, turning Universities into ‘Cowsheds’).

Roger Cohen recently wrote in the New York Times: ‘Nationalism and Authoritarianism, reinforced by technology, have come together to exercise new forms of control and manipulation over human beings whose susceptibility to greed, domination, subservience and fear was not swept away by the fall of the Berlin Wall. Liberty requires certain things. It demands acceptance of our human differences and the ability to mediate them through democratic institutions.’

The future of this world lies in the hands of the rebels, the outcasts, the ‘anti-nationals’. Anti-nationals of the world, Unite!