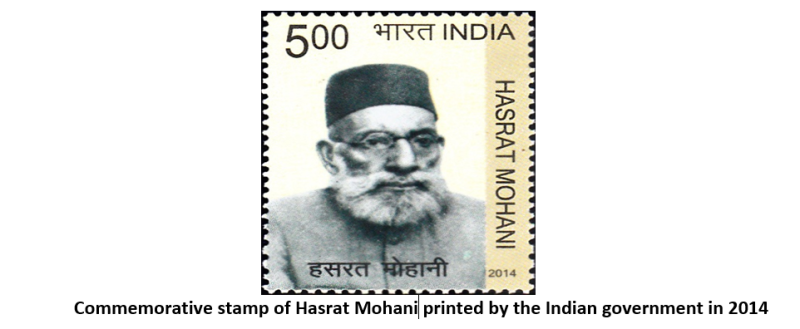

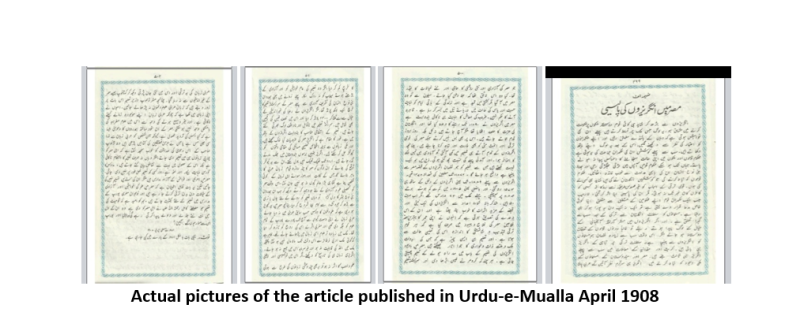

On April 1908, an anonymous article was published in one of the most prestigious Urdu journal of its time ‘Urdu-e-Mualla headed by one of the most celebrated literary giant, then a towering leader of the freedom struggle in India, Maulana Fazlul Hassan commonly known as Hasrat Mohani. The article was abrasively critical to the British policies in India in general and the British occupation of Egypt in Particular. In this the author most blatantly highlighted the deceitful and cunning tactics of the British Crown in waging proxy wars in the name of alleviation of poverty and liberation of humanity to subdue and invade weaker and under privileged countries.

This was the time when Muhammadan Anglo Oriental College in Aligarh (M.A.O later Aligarh Muslim University) had started to turn into a honey pot of freedom struggle. ‘Urdu-e- Mualla’ which he started in 1904 from Aligarh was no ordinary journal but was the best literary-cum- political weekly to which celebrated writers of the country used to contribute. The said article proved to be a catalyst in the already irate situation. The stir created by the article drew the attention of the British authorities who found it illegal and seditious, and therefore approached the owner of the journal. Maulana was asked by the Indian Government to either disclose the name of the author or face charges of instigating revolt. The Maulana, despite all intimidation and an imminent prosecution refused to divulge the name of the author. Resultantly he was convicted and put to prison for two years. The Maulana was perhaps the first political prisoner in British India convicted under the Press laws. Instead of being treated as ‘A’ Class prisoner, he had to undergo a rigorous imprisonment with scanty miserable clothes – a khaki shirt and knickers, a cap, a piece of jute cloth and a rough dirt-laden blanket as his bedding. During the initial period of his stay in the jail he was repeatedly cajoled to give away the name of the author as the British authorities felt uncomfortable having had a man roaming around freely, capable of producing rancorous literature that could help trigger yet another storm of freedom struggle they had been so ruthlessly keeping under the watch.

However, the Maulana did not budge an inch from his stance. The British authorities then, in an effort to squeeze the name of the author turned more precise in their tactics, brutish enough to break any man, let alone a man of letters. He was then slapped a massive fine. When he couldn’t pay the fine, the magistrate confiscated his most treasured possession – his books and rare manuscripts and auctioned them for a paltry sum. He was shifted into a solitary confinement and was made to grind daily one mound of wheat on a stone hand mill which required extraordinary labour to which Maulana was obviously not accustomed. Maulana, in later years wrote in his Urdu-e-Mualla that in the beginning he was much perturbed and distressed by the rigour of jail life, miserable clothing, and lack of water to perform ablution for prayers. But by and by he became habitual to this sort of life. Nevertheless in spite of his trials and tribulations, the Maulana remained steadfast and never revealed the name of the author. A great deal of his literary work, specially the Ghazals, he owes to his imprisonment.

Maulana, is revered as a poet in his own right and it is believed that he wrote poetry in prison. Though there is not any particular segregation of his work as to what all was exclusive to his jail tenure, however most of his Ghazals have a tinge of melancholy with allusions to prison and confinement. He was released from jail in 1910. Much later, on repeatedly being asked about the name of the author who caused him so much trouble, he revealed his name and identity and told that the article was penned by a minor student of MAO College (Later Aligarh Muslim University)of no more than 12 or 13 years. The British, at that point in time were following a ruthless policy without discrimination of capital punishment for anyone found guilty instigating, abetting or arousing fissiparous tendencies. In fact, the article was not anonymous, but Maulana, by his foresight expunged the name of the author. If he had revealed the name of the boy, he would have been rounded up and executed.

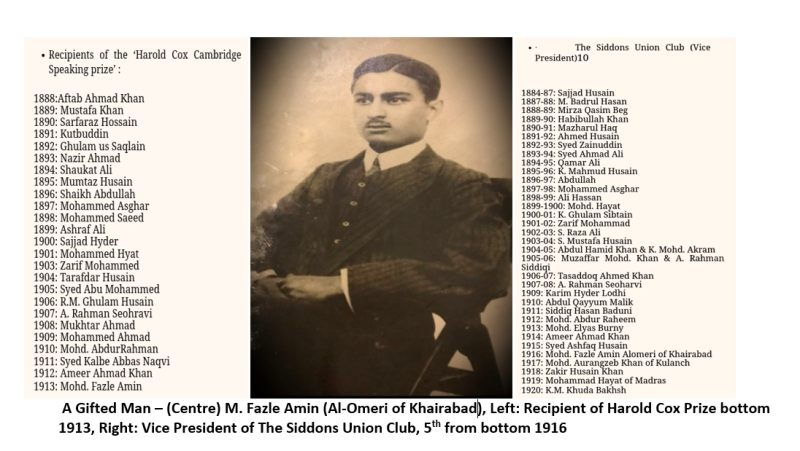

With its frame corroding and the picture inside slowly turning auburn, there hangs in a corner of my study a photograph of a gentleman. Donning an immaculate Edwardian Suit, the gentleman in the photograph looks so regal. I inherited this photograph from my father. The man in the photograph has so much striking resemblance with me that almost all visitors to this place had thought that it was my own photo in black and white. Only a few with a curious eye inquired as to the Edwardian long jacket which looked so antiquated. So much so, during the first few months of my marriage, my wife also took the photograph as that of my own.

The man in the photograph is none other but the author of the same article which had made Maulana Hasrat Mohani grind a mound of wheat daily in the confines of the jail for two years. He was my grandfather Mohammad Fazle Amin (in later life he used the suffix of ‘Al-Umari of Khairabad’ after his clan). My father didn’t remember him as he was either two or three when he passed away while still young. My youngest aunt Nishat Fatima was born six months after his death. I do not know his date of birth but according to Maulana Hasrat Mohani he was twelve or thirteen at the MAO School when he wrote that article published in 1908 in his journal. Making use of the advantage of back counting, his date of birth, giving the fairness of benefit of doubt, should be within the bracket of 1894 and 1896. He had left behind one son and three daughters; my father was the third among the siblings. As a young teen ager, I had heard a lot about him from my father and my aunt Altaf Fatima. But the real treasure came from his son-in-Law Syed Ibne Ahmed, who himself was an Alig and also happened to be his nephew by relation. Later, after the death of Fazle Amin, he married his eldest daughter Rishad. She died in early 50’s. Since Ibne Ahmed was relatively a young man and had seen him in his youth he knew more than what my father and aunts did. According to Syed Ibne Ahmed, Fazle Amin was a fine gentleman with exceptionally fair complexion. His accent of English was so perfect that “if a veil had been put between him and the listener, even the English would take him as an Englishman”. He was a remarkable horse rider. In the words of Ibne Ahmed; “Seeing him at the riding Club at Aligarh inspired me to learn riding.”

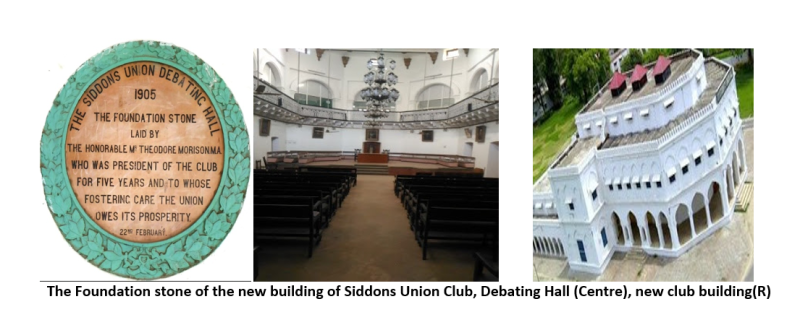

One of the most talked about quality was his stunningly exceptional quality of public speaking. He was the Vice President of the Siddons Union Club and the recipient of the coveted Harold Cox Cambridge Speaking Prize. A desultory research revealed a detailed account of this great institution. A few facts about this would help have an idea of its prestige:-

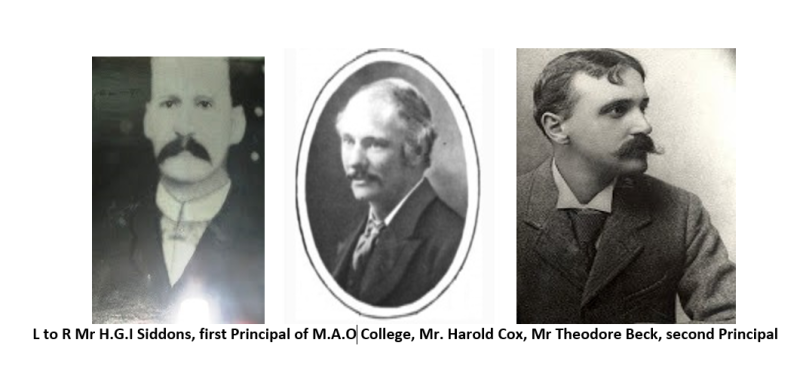

On 25th September 1881, Mr Henry George Impey Siddons, the first Principal of the MAO College announced the formation of a ‘Union Club’ to exclusively nurture the students in the aptitude of public speaking, civilized argument, and energetic debate. On the occasion, the Hon’ble Sir Syed Ahmed Khan proposed that the Principal of the college shall be the President of the Club, whereas the designation of the Vice President and Secretary would be among the most shining members through elections. The Club was named the ‘Siddons Union Club’ to honor the founding Principal. After the retirement of Mr Siddon in 1884, Mr Theodore Beck took over as the second Principal of the College. Being himself a distinguished graduate of Cambridge University and having held the office of the President of the ‘Cambridge University Union Society’ (C.U.U.S) he transformed the Club on the same model. Not only this, he permanently bound the two societies together in permanent affiliation. In 1887, the debating prize was named as the ‘Harold Cox Cambridge Speaking Prize’ after Mr Harold Cox, Professor of Mathematics and Political Economy (Later Member of British Parliament) for his invaluable services in the College.

In 1901, the scheme of extempore debates was introduced which was the first ever concept in India. By 1911, during the time of Mr. Theodore Morison, the third Principal of the college, a separate building with offices and a library, indoor games and a dedicated spacious hall was inaugurated. At that point in time debates were regularly held in English four times a month. Prominent world leaders of their times spoke at the forum. A few of those included Quaide Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Yusuf Jamal Pasha of Ottoman Empire, Mr M.K Gandhi, Jamal El Nasir, Shah of Iran, Anwar El Sadat of Egypt, King Saud Bin Abdulaziz. Through this Club, the students got a dialectical platform at world level to speak their voice from this great seat of learning.

The name of Mohammad Fazle Amin winner of the Harold Cox Cambridge Speaking Prize in 1913 in the recipient list and Vice President of The Siddons Union Club, 1916 can be found in the related searches on the internet. When Fazle Amin was announced the winner of the trophy, the English students present there registered a complaint to the adjudicators to verify his credentials as according to them a person with such a flawless accent could not have been a Hindustani.

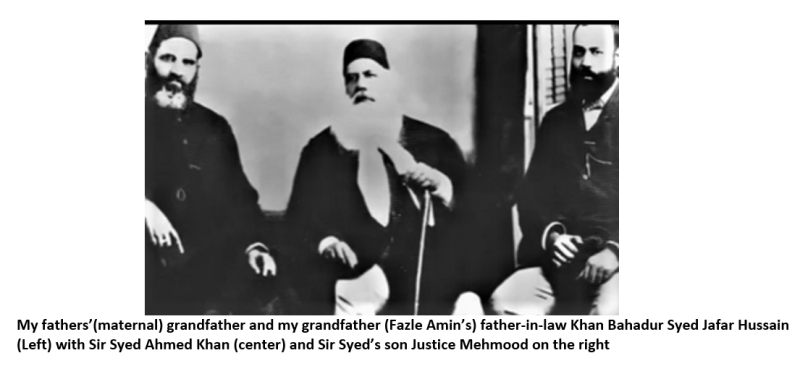

While cobbling together the pieces of the many shades of his life, Fazle Amin’s marriage to my grandmother was also a bit of a story. Khan Bahadur Syed Jafar Hussain was a highly distinguished and reputable gentleman from Lucknow. By profession he was an irrigation engineer and had served as Division and Chief Engineer at various districts. He was the first Muslim in Oudh to rise to this position. During the course of his service he constructed innumerable projects to include dams, bridges and water works all over UP (United Provinces) which till date are spectacle of high degree of excellence of construction. In acknowledgement of his meritorious services the British administration gave him the title of ‘Khan Bahadur.’ He had a great camaraderie with Sir Syed Ahmed Khan who, keeping in mind his thoughts, extraordinary genius, skills and acumen had made him in-charge of all projects of construction of Aligarh school and later college. Khan Bahadur Syed Jafar Hussain performed this duty free of cost. Whenever, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan needed him in connection with construction of new blocks etc, Khan Bahadur would come to Aligarh on leave from wherever he was posted. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan had appointed him the life Member of the College Council and Trustee. As per many credible sources; “every brick used in the blocks and buildings inside Aligarh was laid in front of his eyes.” After the death of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Khan Bahadur Syed Jafar Hussain proposed to elevate the college to the status of a University. In order to meet the colossal expenditure, he proposed the formation of ‘ONE RUPEE FUND’. He estimated a cumulative expenditure, required for the purpose to be around Rs 4,05,708.00. This he vowed to collect in four years time raising one lakh (Rs 100,000) each year.

During one of his visits to the MAO College he happened to visit the great Debating Hall inside the Siddons Union Building where a grand finale of Harold Cox Prize was being held. He watched the entire session of the extempore debates with immense interest as among the competitors there were a few Britons also. On seeing the finale won by a handsome young Indian he was overwhelmed with joy. This was none other but Fazle Amin.

Khan Bahadur Jafar Hussain was a ‘Hussaini Syed’ and did not marry outside his clan. However, the suave and demeanor and the eloquence of speech of the young man moved him so much that he himself approached him asking his hand for his youngest and most beloved daughter Syeda Mumtaz Jahan. At this point in time Fazle Amin’s father Sardar Fazle Matin was Chief Justice High Court of the State of Patiala. He was the grandson of Fazle Imam who had been Sadar-uss- Saduur and Shams-ul-Ulema in Delhi. He was mentor of Ghalib who had said a number of verses in his honor.

Soon after his M.A from Aligarh, Fazle Amin was married to Khan Bahadur Syed Jafar Hussain’s youngest daughter with the consent of both families.

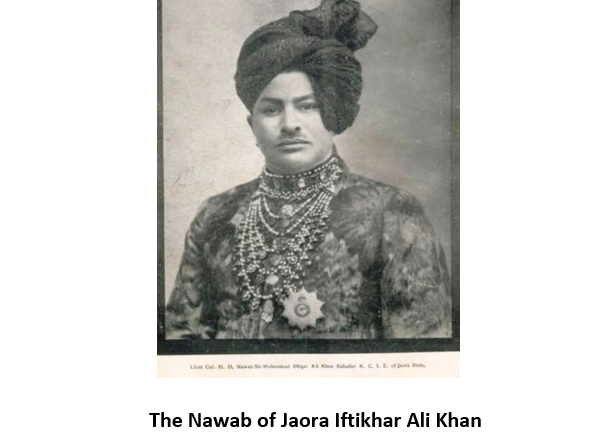

Fazle Amin’s friendship with the Nawab of Jaora, Iftikhar Ali Khan (b. 1883, reign. 1895-1947 Full title; Lieutenant Col H.H Fakhr ud-Daula, Nawab Sir Muhammad Iftikhar Ali Khan Bahadur, Saulat Jang, Nawab of Jaora GBE, KCIE) was fortuitous. In those days it was voguish for the Rajahs and Maharajahs of the hundreds of Princely States to send their representatives to various esteemed educational institutes of the country and cherry-pick the most meritorious students to be employed on various key positions in their respective states. Fazle Amin, following his M.A, was spotted by one such team from the State of ‘Jaora’. The reason for his selection was not only his educational career but his superb prowess as a rider and a polo player. He remained lackadaisical for some time for he thought his motherland required him, unshackling the yolk of slavery, more than anything else. But certain events with regards to his father forced him to take up the job. The Maharaja of Patiala Bhupinder Singh (1900-1938) was an obnoxiously wicked, hideous, and despicable character with 365 wives, consorts and concubines. He could be termed as the very manifestation of a being endowed with all the vices and evil in one. He wanted to convict certain relatives on fake charges. The case was referred to the State High Court with clear instructions from the Maharajah to his Chief Justice (Fazle Mateen). The Chief Justice carried out the trial with diligence and in the end (remaining true to his family) gave the verdict against his own Maharaja along with the letter of his resignation. The same day he packed his belongings and left Patiala for his native town of Khairabad (80kms from Lukhnow). Resultantly his property and even the personal house were confiscated by the orders of the Maharaja. Owing to the situation at home, Fazle Amin had no other choice but to accept the job at Jaora.

Jaora was a small State with an area of 700 Square miles in Central India neighboring Bhopal and Indore. It was a few hours journey from ‘Jhansi’ (The Bhowani junction of John Masters). Jaora, in proportion of its size, had all the trappings of a semi-independent principality with its own judiciary, currency and revenue system. It also had its own police force, backed by units of cavalry, infantry and artillery. The Nawab (Iftikhar Ali Khan) was a leading polo player of his time in India with a handicap of seven. Educated at esteemed institutions, he was a man of good taste and hobbies. He was an honorary commission and had been attached with 2nd Central India Horse. From Polo his interest shifted to Fox hunting with hounds. As a result Jaora became a hub of this sport which the British had brought from England. Every year around Christmas and New Year, the grounds adjoining the palace used to turn into a festive tent-city to house the guests from the British army and the Indian Civil and Political Services who came for duck and partridge shoots, polo and other horse and hound sports. Nawab Iftikhar Ali Khan who was, though, around 12 years older found many similarities in the young man in his service. During the innumerable fox hunting sprees in which Fazle Amin would accompany him, the two came closer and quickly the official relationship turned into more of a friendship. The Nawab adoring his brilliance and intellect soon promoted him to his highest post of Chief Minister.

But the heart and soul of Fazle Amin was in Aligarh. Bearing the torch of freedom was more important for him than anything else. Though, Aligarh was pretty far off from Jaora (around 700 kms), Fazle Amin would find a way to frequently embark on the train to Aligarh. There he would warm the hearts of the students with his invigorating speeches.

His speeches bore fruits for Aligarh in later years was to become the “Mini Pakistan” (as it was then known). He was the biggest proponent of the ‘One Rupee Fund’ instituted by his father-in-law Khan Bahadur Syed Jafar Hussain. The M.A.O College won the status of University and became Aligarh Muslim University in four years time in 1920. The struggle for freedom which he started with his speeches in Aligarh University, slowly, but definitely transformed into the struggle for Pakistan. Pakistan emerged on the map of the world in 1947.

And like a missing page of a book that leaves a permanent void in the story forever, Fazle Amin, too left a small dot somewhere in the long story of Pakistan. But the story must go on. They say that there are only two races of men in the world; the race of the decent man –and the race of the indecent man. He indeed belonged to the former one.

Fazle Amin died in his sleep while still young –probably in 1930, at around the age of 35*. Thus, the soul who appeared on the canvas of life by an anonymous essay, who lived a life of anonymity while keeping the flame of freedom alive, and whose heartwarming beautiful speeches still echo the archways of the Siddons Union Club building Aligarh University, lost in obscurity forever.

Perhaps, he was yet another of the soul, for whom Thomas Gray’s long elegy, written in a lone country churchyard, now known as the “poem of the poems” that believed to speak for many occasions, was meant for.

“Full many a gem of purest ray serene,

The dark unfathom’d caves of ocean bear;

Full many a flower is born to blush unseen,

And waste it’s fragrance on the desert air.”

Thomas Gray

*My father was born in the year 1927 as per his actual date of birth. He was around three when his father died.

Post Script

After passing away of my grandfather, my grandmother became a widow in her very prime youth. She never remarried and shifted to Lukhnow with her father Syed Jafar Hussain. Knowing well her ego, her father built two small houses for her to settle in one and have the other on rent for sustenance. When my aunt Altaf Fatima (elder to my Father) was barely eleven or twelve, she wrote a letter, which was more of a child play, to the then Viceroy Hind Lord Linlithgow (1936 – 1943). The letter was written with a lead pencil using the page of her school note book. The envelope was also made by her with another page. In the letter she, (in the language a twelve year old is expected to use and the stories she must’ve overheard from her elders) wrote as to how their personal property was confiscated by Maharajah Bhopinder Singh. She dropped it in a letter box without anyone’s knowledge. In a few weeks time a few uniformed men arrived with a letter from the Viceroy. The letter was personified by using the direct speech “I”. According to its contents; a team was dispatched on his personal orders to Patiala to find out the truth and to put up the facts to him. In the end it was personally signed with the words; “YOUR HUMBLE SERVANT, LINLITHGO. Following a month or so, the house at Patiala and a considerable land was restored in my father’s name.

References

· Musharraf Ahmed; Shah Hussain Haqeeqat

· Raza Naeem; The Moods of Hasrat Mohani

· Farrukh Akhtar; The Siddons Union Club

· Sultan M. Khan; Memories and Reflections