| Sixty-two years ago, in the month of February, and shortly after Air Marshal Asghar Khan was appointed C-in-C (Commander in Chief), the Pakistan Air Force performed a feat that had so far not been attempted by any other air force with jet aircraft. |

The affairs between Pakistan and Afghanistan were strained since Independence due to the latter’s support for an independent ‘Pakhtunistan’. Diplomatic relations were resumed after a visit by President Iskander Mirza to Afghanistan in 1957 and King Zahir Shah agreed on a return visit, which was fixed for February 1958. The Government of Pakistan decided that it needed to impress their oft-belligerent neighbour with an air display and firing demonstration.

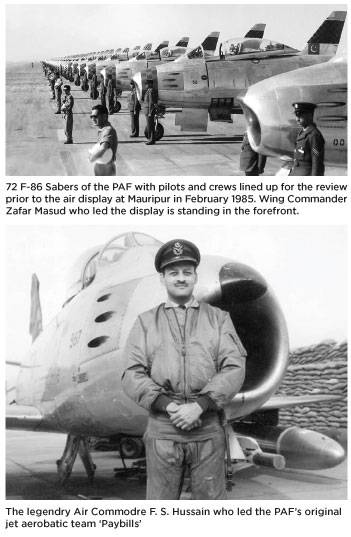

Asghar Khan, the architect of the modern PAF, selected Wing Commander Zafar ‘Mitty’ Masud to lead the air display. Mitty Masud had been commissioned into the Royal Indian Air Force in 1946 and during the Kashmir War, had flown missions from Skardu. He was one of the first to fly the ‘Attacker’ jet aircraft and was a member of the PAF original jet aerobatic team ‘Paybills’ led by F S Hussain, who was a legend in his own right. Mitty’s team consisted of six squadron leaders—Nazir (Bill) Latif, SU Khan, Ghulam Haider, SM Ahmad, Aftab Ahmad, Sadruddin, and nine flight lieutenants—Sajjad (Nosey) Haider, AU Ahmad, Hameed Anwar, Muniruddin Ahmad, Arshad, Jamal Khan, AMK Lodhie, Wiqar Azim and Middlecoat. Most of these pilots would prove to be heroes in the 1965 War, with Mitty earning a Hilal-e-Jurat, Pakistan’s second highest gallantry award.

King Zahir Shah was flown to the Mauripur Airbase in a Viscount aircraft accompanied by President Iskander Mirza and was received by the C-in-C of the PAF. Present were the C-in-Cs of Iran, Iraq and Turkey, ambassadors, ministers, the elite from military and civil, members of the US Military Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG) and the international and domestic press. The base had a huge parking apron, nearly a kilometre long constructed during the Second World War, on which 72 Sabres, their pilots and aircrew stood in what seemed to be a never ending line. Following the Royal review, 36 Sabres taxied out for the display. The first four ships came running in towards the show centre in a diamond formation, switched on their after-burners and climbed to 20,000 feet. As they looped down for a Bomb Burst manoeuvre, the aircraft separated and went supersonic. Each produced a double sonic boom that shook the guests and the 30,000 spectators who had come to see the PAF in action.

Shortly after, four flights each of four Sabres were airborne. As they turned and headed east, the commentator drew the attention of the guests to two Sabres coming in for a low pass. One was trailing the flag of Pakistan and the other a banner with a greeting. Meanwhile the four flights were assembling and positioning themselves for the run-in, six nautical miles to the right of the spectators stand. Closing up to the lead flight with a gentle touch of the throttle, the other three flights neatly slotted into position to form one large diamond of 16 aircrafts. Weeks of training had prepared them for this moment but the pilots were understandably tense which was good as it made the adrenaline flow and sharpened concentration.

The formation approached Mauripur from the east, heading into a steady crosswind coming in on the port side from the Arabian Sea. Below was the densely populated city of Karachi with its maze of streets, above was a brilliantly clear and blue sky. The leader altered course to adjust for wind and maintain the correct approach path. It had to be done gently since a small movement of his aircraft required a greater adjustment on the fringe of this large formation. The flight was approaching parallel to the grandstand four nautical miles ahead and even from this distance the dark mass of spectators and vehicles was visible. The pilots made a quick final check; altitude altimeter—5,200 feet, sufficient height to obviate chances of a bird hit; fuel—the Sabre had an endurance of only 30 minutes but there was enough in the tanks to complete the display and land; engine—7000 rpm, adequate to give 85 percent power; airspeed—a little below the ideal 420 knots. The leader resisted touching the throttle—the others had enough to do without chasing his throttle movements. Three miles to go and a call from the air controller that the two Sabres towing the banners had exited and the formation was clear to commence its manoeuvre dot on time.

The clock was touching 9.55 when the commentator invited the audience to look to their right to see 16 F-86 Sabres approaching for a manoeuvre that would be the centrepiece of the display and no air force in the world had yet demonstrated. To the spectators it seemed that the Sabres were so close that their wingtips were nearly touching but in actual fact the aircraft flying line astern were just beneath the jet efflux and the slipstream of the one ahead. The whole formation was stacked below the leader, each pilot concentrating on the aircraft on which he was formatting, with perfect synchronisation between his eyes and the hand on the control stick. Down below, the airfield perimeter slipped by and it was the cue to begin the manoeuvre. The leader warned the formatting pilots, eased back firmly but steadily on the control column and Sabres tied together by an invisible force rose upwards. As the airspeed fell the leader resisted the temptation to apply more throttle. The speed and inertia were ample to fly over the top of the loop provided the radius remained correct by maintaining just sufficient back pressure on the control column. Too much or too little and 16 aircraft would have stalled with disastrous consequences.

Now standing vertically on their tails, the Sabres had passed the point of no return and were committed to the manoeuvre. Mitty Masud had a quick look in the mirror to confirm that the formation was perfect. His next immediate concern was to remain perpendicular to the ground. A slight tilt and the whole formation would have veered with a break in the symmetry but the sky above provided no reference point to gauge direction. However, as he neared the summit, he threw his head well back and the view of a level horizon confirmed that the flight path was still vertical. All well so far but now the next difficult stage. Since the formation was stacked down, the arc of the flight paths of the aircraft at the rear was larger than those in front. Applying greater engine power to maintain station nearing the top of the loop was impractical. The throttle did not respond well at low airspeeds as turbine engines have a slight lag when power is applied. Thus while, the rear aircraft are decelerating as those in the lead cross the summit, gravity rapidly accelerates their speed and the spacing between the aircraft increases. Using air breaks by the lead aircraft would cause too much air turbulence for precision flying.

The solution was simple. The pilots in front delayed the downward plunge by relaxing the back pressure on the control column and holding an inverted position at 10,000 feet floating nearly level with the horizon. Another glance in the mirror by the leader confirmed that the rear aircraft were topping the loop and he eased back on the control column for the exhilarating dive. The speed gave a renewed crispness to the feel of the controls and the formation looked as if it was packed even closer together than before with mere feet separating wing-tip from wing-tip. As the Sabres levelled off at 5,000 feet and exited with the fading roar of sixteen General Electric J47 Turbojet engines, to the spectators the entire manoeuvre which lasted not more than 30 seconds, seemed effortless. The next event was formation aerobatics by seven Sabres still led by Mitty Masud which was followed by a single aircraft demonstrating the Sabre’s ability to perform a four- and eight-point roll. The final event in the air display was formation aerobatics by another group of four Sabres from the Falcon team.

The first item in the firing demonstration that followed was the strafing of ground targets by four Sabres. The Sabre had heavy internal armament of six Point 50 M3 Browning machine guns with 1,800 rounds of ammunition and the effect on the targets was devastating. So also were the ground attacks by six Sabres firing salvos of 3.5 inch rockets. Just as the air display commenced with the dramatic sonic booms, the firing demonstration concluded in the most dramatic manner with a fiery Napalm attack and the almost nuclear like mushroom of smoke that billowed into the sky. Much to the relief of the PAF, the entire sequence of events of the flying display and the firing demonstration were conducted flawlessly. But what happened afterwards was alarming. Thousands of spectators swarmed towards the Sabres parked on the large apron, touching and pulling everything with some even getting into the cockpits. The few ground crews tried desperately to keep them away from the machines.

In September the same year, the air display team of the Royal Air Force named the Black Arrows established an unbeaten world record at Farnborough with a loop by a formation of 22 Hawker Hunters. Few are aware that the Black Arrows were inspired by the display by their counterpart in the Pakistan Air Force seven months earlier. The description of the loop by the Falcons in this article has been adapted from a narrative by the Air Commodore Roger Topp, who led the Black Arrows. In 1961, Flight Lieutenant Hameed Anwar, who was a veteran of the PAF’s aerobatics team, went on an exchange posting with the RAF and flew with the British ‘Blue Diamonds’ at the Farnborough Air Show. In 1964-1965, he also trained and led ‘The Hashemite Diamonds’, the air display team of the Jordanian Air Force.