The summer of 1943 was a bad time for the British Indian Army in Burma. Having surrendered the whole of the country to the Japanese the previous year, a limited counteroffensive (the First Arakan Campaign) launched by the 14 Indian Infantry Division to retake the port of Akayab had stalled. With their skill in jungle warfare, a much smaller Japanese force of two regiments was pushing the 14 Division (reinforced by brigades of the 26 Indian Infantry Division) back towards its base at Cox’s Bazar. The Indian brigades, many of whom had been engaged for long and continuous periods, were tired. Battle casualties had not been very severe but malaria and fever had exacted a very heavy toll. Reinforcements were also arriving untrained and completely unfit to play their part in the operation. Morale was very low and the Japanese psychologically dominated. The division was attempting to stem the advance by the 55 Division of the Imperial Japanese Army astride the Mayu Range by defending the flood plain of the River Naf to its east and the Mayu River Valley to its west (Further north the river is called Kalapanzin). It was fighting at the end of a long and precarious Line of Control (LoC) while the Japanese were comparatively close to their base at Akyab.

1/15 Punjab was part of 123 Indian Infantry Brigade. It was one of the oldest battalions of the British Indian Army that had been originally raised as the 25 Punjabis in 1857 and taken part in the Second Afghan War. The 123 Brigade had spearheaded the advance by 14 Division on the east of the Mayu River but in early Feb 1943 had failed to capture the key position of Rathedaung opposite Donbaik. The inexperience of the brigade and its units (including 1/15 Punjab) was demonstrated by the fact that the attack was launched against well-prepared positions in daylight with insufficient artillery and no smoke to cover the assault. Across the river an attack on Don Baik (opposite Rathedaung) also failed and as 14 Division started falling back against relentless Japanese pressure, 1/15 Punjab went under the command of the 55 Indian Infantry Brigade and was ultimately deployed in the area of Buthidaung.

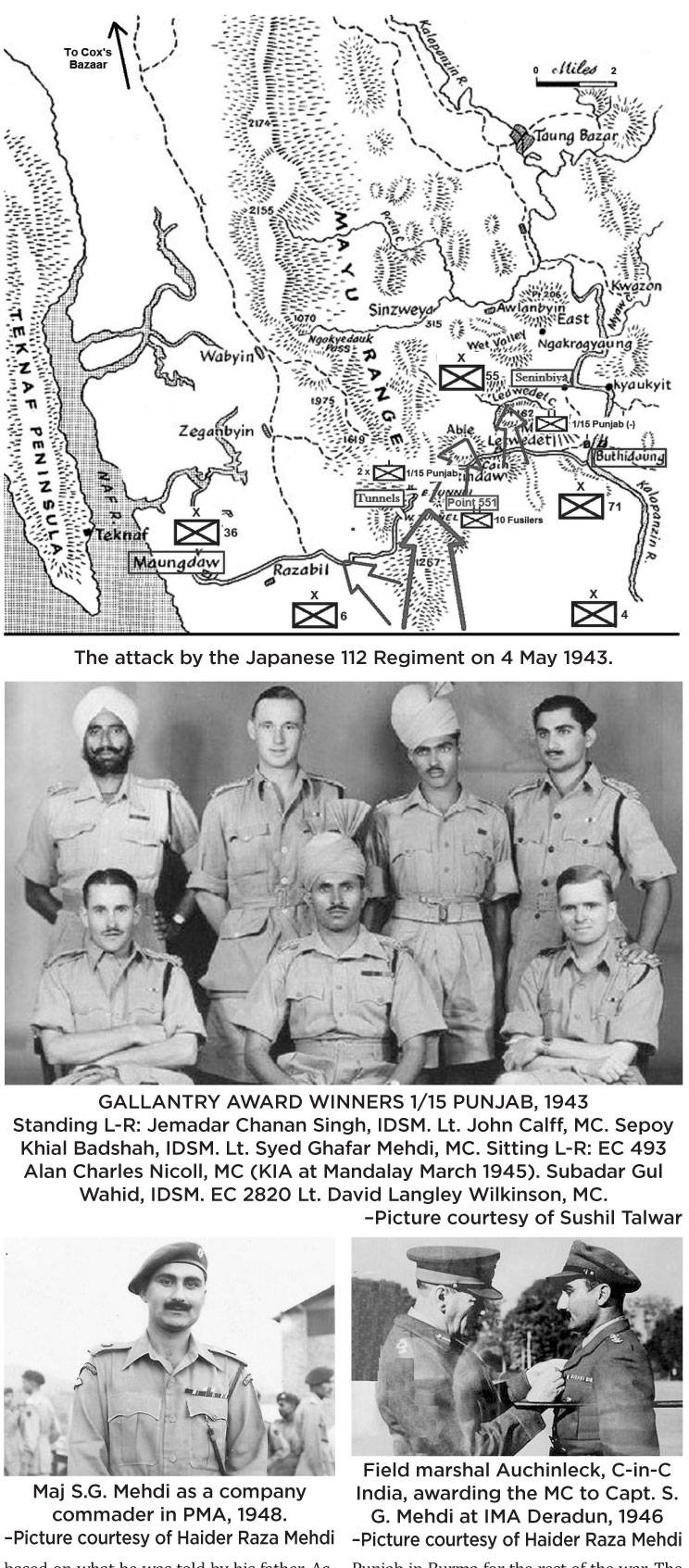

In early April 1943, a regiment of the 55 Division routed a British brigade by crossing the precipitous and jungle-covered Mayu Range (at a point where British officers had regarded the range as impassable) and cut the track along the River Naf. It now advanced northwards towards Maungdaw while a second regiment advanced up the valley of the River Mayu. A Japanese force also advanced along an elephant trail on the spine of the Mayu Range and broke through 7/15 Punjab, which was sent to oppose it. At this belated stage, the headquarters of the Indian XV Corps under Lieutenant General Slim took charge of the Arakan Front. Slim rightly anticipated that the Japanese were heading for the Maungdaw-Buthidaung road to cut the LoC of the brigades in the Kalapanzin river valley and if his brigades in the two-river valley held their positions, there was an opportunity to trap and destroy the Japanese force advancing along the Mayu Range. The defence formed a horseshoe with a British battalion and two companies of 1/15 Punjab deployed at its apex in the area of the tunnels on the Maungdaw-Buthidaung Road, and two battalions were tasked to encircle the Japanese as they neared the road and slam the trapdoor shut.

Lt Syed Ghaffar Mehdi was serving as a company officer with the remainder of the battalion deployed in the area of Buthidaung. He belonged to an illustrious family which traced its lineage to Imam Hussain, the grandson of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) who was martyred at Karbala. He had been commissioned only six months earlier and probably joined the battalion during its failed attack on Rathedaung. Like the rest of the division he had no training in jungle warfare but the action for which he was awarded an MC shows that he had quickly grasped the essentials and what he didn’t know he made up with sheer guts and determination. By the end of April, the Japanese advancing in small and well dispersed groups to escape detection, had contacted the defences along the Maungdaw-Buthidaung road. On the night of April 2, S G Mehdi led a small recce patrol to determine if the Japanese were present in a nallah. Finding strong evidence of their presence, he probed further and clashed with a Japanese patrol.

There are two varying accounts of the subsequent action—one contained in his citation and the other in a beautiful obituary written by Syed Haider Raza Mehdi on the death of his father in 2015. His citation states that when the scouts gave a warning of the approach of the Japanese, the officer set up an ambush and, having allowed two enemy scouts to pass only 12 yards away, opened fire on the main body. The citation credits Mehdi with personally killing five of the seven Japanese and “…his blood soaked shoes amply testified to a daring act which was not only an inspiration to the men, but an example to his fellow officers”. The differing account recorded by his son is obviously based on what he was told by his father. According to S G Mehdi, there was no planned ambush but a clash with a Japanese patrol in which both sides were equally surprised and opened fire as they hit the ground. When the firing subsided, Mehdi found he was all alone. Ignoring a call to surrender, he surprised the Japanese from an unexpected direction and killed all ten of them. He then searched for the bodies of his own patrol and when he found none, “…he collected the Samurai sword of the Japanese officer and other evidence of his encounter with the Japanese, too gruesome to describe”. With his boots covered in blood up to his ankles he returned to the battalion headquarters. His patrol had bolted and informed the battalion that the ‘Captain Sahib’ had been gunned down while valiantly fighting and in spite of their best efforts they could not retrieve his body.

One can only guess why the battalion ‘spun a yarn’ in the citation that so differs from the actual account but it was probably to cover-up the timidity of the troops. In any case, the Japanese sword and the other ‘gruesome evidence’ that Mehdi brought back was proof enough of his deed and valour and earned him an MC. It also earned him the nickname of ‘Killer’ Mehdi that stuck with him throughout his career. The citation was endorsed by General Auchinleck, C-in-C India on 15 Jul 1943, only a few weeks after he resumed command of the British India Army and appeared in a Gazette Notification on 19 August the same year. “The King has been graciously pleased to approve the following awards in recognition of the gallant and distinguished service in Burma—The Military Cross—Second-Lieutenant Syed Ghaffar Mehdi, 15th Punjab Regiment, Indian Army.”

However, coming back to the events of May 1943, Slim’s plan to trap the Japanese unfortunately failed. A British battalion was defending Point 551, a key hill feature for protecting the approach to the tunnels on the Maungdaw-Buthidaung road.

‘Killer’ Mehdi continued to serve with 1/15 Punjab in Burma for the rest of the war. The battalion had fought well in the Arakan and was converted into the division recce battalion for the 19 Indian Infantry ‘Dagger’ Division. As a recce battalion, 1/15 Punjab was always at the spearhead and when the Union Jack and the insignia of the Dagger Division was raised on Fort Duffrin at Mandalay, alongside flew the flag of 1/15 Punjab.

After the war, S G Medhi was selected to serve as an instructor at the prestigious Indian Military Academy at Dehradun where in December 1946, the Auk (who had recently been promoted Field Marshal) formally awarded the officer the Military Cross. During the tragic period of the partition of the subcontinent, he was a member of the boundary force transferring refugees between India and Pakistan and saved thousands on both sides from certain death. After Independence, he was the first company commander of Qasim Company in the newly raised Pakistan Military Academy and many future general officers were his cadets.

In January 1964, he was appointed the third Group Commander of the Special Services Group (SSG). Against the wishes of the USA military advisers transformed its role from a stay-behind force in case of invasion into a commando regiment for conducting Special Operations. However, he opposed the manner in which his force was employed during the 1965 War and was proved correct but it cost him his command. He was posted as Col Staff 15 Division in Sialkot during the crucial days of the 1965 War but fell afoul of Maj Gen Tikka. SG Mehdi was a brilliant officer but his forceful nature was unacceptable in the prevailing military culture and after being superseded, he chose to retire. It was a great loss to the Pakistan Army.

Author’s Note: The details of his career in the Pakistan Army have been extracted from the article ‘Col. S.G. Mehdi MC. The passing away of a Great Warrior’. It was written by his son Syed Haider Raza Mehdi, who also provided the photographs. The writer can be contacted at syedali4955@gmail.com.

1/15 Punjab was part of 123 Indian Infantry Brigade. It was one of the oldest battalions of the British Indian Army that had been originally raised as the 25 Punjabis in 1857 and taken part in the Second Afghan War. The 123 Brigade had spearheaded the advance by 14 Division on the east of the Mayu River but in early Feb 1943 had failed to capture the key position of Rathedaung opposite Donbaik. The inexperience of the brigade and its units (including 1/15 Punjab) was demonstrated by the fact that the attack was launched against well-prepared positions in daylight with insufficient artillery and no smoke to cover the assault. Across the river an attack on Don Baik (opposite Rathedaung) also failed and as 14 Division started falling back against relentless Japanese pressure, 1/15 Punjab went under the command of the 55 Indian Infantry Brigade and was ultimately deployed in the area of Buthidaung.

In early April 1943, a regiment of the 55 Division routed a British brigade by crossing the precipitous and jungle-covered Mayu Range (at a point where British officers had regarded the range as impassable) and cut the track along the River Naf. It now advanced northwards towards Maungdaw while a second regiment advanced up the valley of the River Mayu. A Japanese force also advanced along an elephant trail on the spine of the Mayu Range and broke through 7/15 Punjab, which was sent to oppose it. At this belated stage, the headquarters of the Indian XV Corps under Lieutenant General Slim took charge of the Arakan Front. Slim rightly anticipated that the Japanese were heading for the Maungdaw-Buthidaung road to cut the LoC of the brigades in the Kalapanzin river valley and if his brigades in the two-river valley held their positions, there was an opportunity to trap and destroy the Japanese force advancing along the Mayu Range. The defence formed a horseshoe with a British battalion and two companies of 1/15 Punjab deployed at its apex in the area of the tunnels on the Maungdaw-Buthidaung Road, and two battalions were tasked to encircle the Japanese as they neared the road and slam the trapdoor shut.

Lt Syed Ghaffar Mehdi was serving as a company officer with the remainder of the battalion deployed in the area of Buthidaung. He belonged to an illustrious family which traced its lineage to Imam Hussain, the grandson of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) who was martyred at Karbala. He had been commissioned only six months earlier and probably joined the battalion during its failed attack on Rathedaung. Like the rest of the division he had no training in jungle warfare but the action for which he was awarded an MC shows that he had quickly grasped the essentials and what he didn’t know he made up with sheer guts and determination. By the end of April, the Japanese advancing in small and well dispersed groups to escape detection, had contacted the defences along the Maungdaw-Buthidaung road. On the night of April 2, S G Mehdi led a small recce patrol to determine if the Japanese were present in a nallah. Finding strong evidence of their presence, he probed further and clashed with a Japanese patrol.

There are two varying accounts of the subsequent action—one contained in his citation and the other in a beautiful obituary written by Syed Haider Raza Mehdi on the death of his father in 2015. His citation states that when the scouts gave a warning of the approach of the Japanese, the officer set up an ambush and, having allowed two enemy scouts to pass only 12 yards away, opened fire on the main body. The citation credits Mehdi with personally killing five of the seven Japanese and “…his blood soaked shoes amply testified to a daring act which was not only an inspiration to the men, but an example to his fellow officers”. The differing account recorded by his son is obviously based on what he was told by his father. According to S G Mehdi, there was no planned ambush but a clash with a Japanese patrol in which both sides were equally surprised and opened fire as they hit the ground. When the firing subsided, Mehdi found he was all alone. Ignoring a call to surrender, he surprised the Japanese from an unexpected direction and killed all ten of them. He then searched for the bodies of his own patrol and when he found none, “…he collected the Samurai sword of the Japanese officer and other evidence of his encounter with the Japanese, too gruesome to describe”. With his boots covered in blood up to his ankles he returned to the battalion headquarters. His patrol had bolted and informed the battalion that the ‘Captain Sahib’ had been gunned down while valiantly fighting and in spite of their best efforts they could not retrieve his body.

One can only guess why the battalion ‘spun a yarn’ in the citation that so differs from the actual account but it was probably to cover-up the timidity of the troops. In any case, the Japanese sword and the other ‘gruesome evidence’ that Mehdi brought back was proof enough of his deed and valour and earned him an MC. It also earned him the nickname of ‘Killer’ Mehdi that stuck with him throughout his career. The citation was endorsed by General Auchinleck, C-in-C India on 15 Jul 1943, only a few weeks after he resumed command of the British India Army and appeared in a Gazette Notification on 19 August the same year. “The King has been graciously pleased to approve the following awards in recognition of the gallant and distinguished service in Burma—The Military Cross—Second-Lieutenant Syed Ghaffar Mehdi, 15th Punjab Regiment, Indian Army.”

However, coming back to the events of May 1943, Slim’s plan to trap the Japanese unfortunately failed. A British battalion was defending Point 551, a key hill feature for protecting the approach to the tunnels on the Maungdaw-Buthidaung road.

‘Killer’ Mehdi continued to serve with 1/15 Punjab in Burma for the rest of the war. The battalion had fought well in the Arakan and was converted into the division recce battalion for the 19 Indian Infantry ‘Dagger’ Division. As a recce battalion, 1/15 Punjab was always at the spearhead and when the Union Jack and the insignia of the Dagger Division was raised on Fort Duffrin at Mandalay, alongside flew the flag of 1/15 Punjab.

After the war, S G Medhi was selected to serve as an instructor at the prestigious Indian Military Academy at Dehradun where in December 1946, the Auk (who had recently been promoted Field Marshal) formally awarded the officer the Military Cross. During the tragic period of the partition of the subcontinent, he was a member of the boundary force transferring refugees between India and Pakistan and saved thousands on both sides from certain death. After Independence, he was the first company commander of Qasim Company in the newly raised Pakistan Military Academy and many future general officers were his cadets.

In January 1964, he was appointed the third Group Commander of the Special Services Group (SSG). Against the wishes of the USA military advisers transformed its role from a stay-behind force in case of invasion into a commando regiment for conducting Special Operations. However, he opposed the manner in which his force was employed during the 1965 War and was proved correct but it cost him his command. He was posted as Col Staff 15 Division in Sialkot during the crucial days of the 1965 War but fell afoul of Maj Gen Tikka. SG Mehdi was a brilliant officer but his forceful nature was unacceptable in the prevailing military culture and after being superseded, he chose to retire. It was a great loss to the Pakistan Army.

Author’s Note: The details of his career in the Pakistan Army have been extracted from the article ‘Col. S.G. Mehdi MC. The passing away of a Great Warrior’. It was written by his son Syed Haider Raza Mehdi, who also provided the photographs. The writer can be contacted at syedali4955@gmail.com.