By Asif Javed

As one enters the famous Borh House in Kalabagh, one is struck by its beauty. Borh House once served as Nawab of Kalabagh’s (NOK) guest house for his personal friends and visiting dignitaries, which included many heads of state. A young Shah Faisal stayed there. Its location, right on the western bank of the mighty Indus, is picture perfect.

The pictures on the walls and the decorations tell a lot of stories of the bygone era. NOK was once the second most powerful man in Pakistan; this was also where he would breathe his last. The present generation may not know much about him but no history of Pakistan is complete without mentioning his six years of absolute rule over what was then West Pakistan.

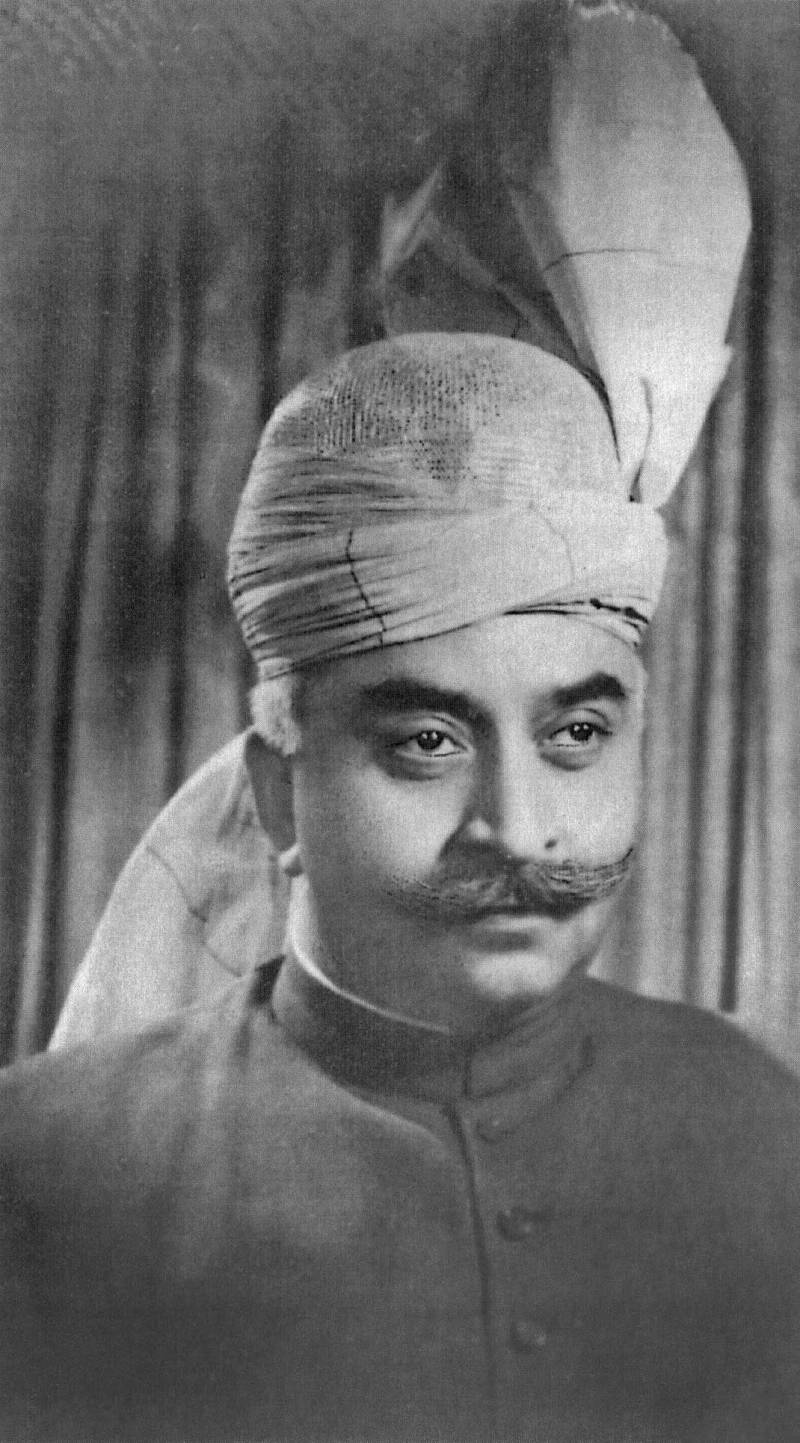

Nawab Amir Mohammad Khan of Kalabagh (1910–1967) was the scion of a feudal family. In his youth, he developed a reputation for brutality—an unfortunate prerequisite for survival in rural society, some might say that it helped him gain the upper hand over his opponents, the Niazi Pathans of Essa Khel and Pir of Mukhad. He participated in the historic gathering at Manto Park, Lahore and made a substantial donation to Muslin League in 1940 when the Pakistan Resolution was passed. His swift rise to power was helped by the fact that he owned some hunting grounds that he used to entice people in high places with, men like Ayub Khan and Iskander Mirza. Z A Bhutto had used the same tried and trusted formula to get close to the duo. Of heavy built, NOK wore traditional Punjabi dress, had a huge moustache and was old fashioned in many ways; he had been educated in Atchison and London, and spoke good English. Ayub was impressed and made him Governor of West Pakistan preceded by a short stint as chairman of PIDC. This unusual partnership between the military dictator and a feudal lord was to last six years.

NOK governed West Pakistan with an iron hand; he developed a reputation for being a harsh administrator who remained well informed. His system of intelligence was almost flawless, based primarily on direct reports from the district administration and personal contacts. He once surprised Jahandad Khan, his military secretary, by telling him that before approving his appointment, he had looked deep in to Jahandad’s family background and knew that his grandfather was the first in his area to have performed the Hajj. NOK was financially clean. Decades after his exit, no financial scandals were associated with him or his family. There is no evidence that his assets increased while he was in power. He was very punctual and hard working. Keenly aware of the dangers of nepotism, he kept his family at a distance; they were not allowed to stay at the Governor House. Muzzafar, his eldest son and heir apparent, was once harshly reprimanded by the Governor when he tried to sit with his father in the back seat of the official car; the Governor made him sit in the front seat with the driver saying that the back seat was meant for his military secretary.

NOK drew no salary and did not avail himself of any benefits from his all-powerful post. He was fiercely loyal to Ayub and would insist on mentioning the President’s name in his monthly radio broadcasts at least three times.

He was also outspoken, and perhaps the only one who dared to warn Ayub about his family’s corruption. On one such occasion, when he broached this subject, Ayub was overheard telling him, “Do my sons not have a right to live in this country?” NOK was taken aback and later remarked in frustration that Ayub’s decline would be hastened by his son’s bad reputation. Shahabnama has a reference to one of Ayub’s infamous sons who led a procession in Karachi after the rigged 1965 elections that resulted in violent clashes with the supporters of Miss Fatima Jinnah. Scores died and the exact body count is unknown to this day. Decades later, the same son, while a member of Nawaz Sharif’s cabinet, used administrative pressure to get his car registration from Gujranwala so that he could proudly display, GA 1. This most unfortunate tradition of protecting one’s corrupt loved ones has persisted and flourished in Pakistan; the most recent example being the son of a recently retired chief justice of the Supreme Court; while the publicity seeking father was generating headlines with his suo motos, the son had been enjoying his right to live in Pakistan.

Back to NOK: when asked to join the Convention League, he declined and was overheard saying, “Keep me out of that dirt.” He was also not in favour of Operation Gabraltar that was Bhutto’s brainchild; he once remarked in despair that Ayub’s foolish advisors would bring his downfall.

NOK was against Yahya Khan’s promotion to the post of chief of Pakistan Army and said so. Yahya’s fondness for alcohol and reputation as an inveterate lecher had not escaped the ever vigilant Governor. Ayub obviously ignored his advice. The self-proclaimed Field Marshal was by then surrounded by sycophants, for some of whom, he had become Daddy. Many would argue that Yahya’s promotion was a watershed moment in the history of Pakistan.

NOK submitted his resignation in 1966, having realized that he no longer had the President’s confidence. For some time, there had been a strain in their relationship. The last straw was an election at Karachi where Ghaus Bux Bazanjo won with NOK’s support against the official candidate of the Convention League. The parting of ways was amicable, unlike Ayub’s dismissal of Bhutto. NOK drove up to Rawalpindi, had lunch with the President, exchanged pleasantries and went home to Kalabagh, having bid a final farewell and that was it; they were never to meet again.

Within a year of NOK’s departure, all had gone awry. West Pakistan was in turmoil. Yahya Khan easily pushed out the ailing Ayub. Sometime after his fall from power, Ayub’s wife was overheard telling an acquaintance, “NOK’s dismissal was a mistake by Khan Sahib (Ayub)”. One wonders if her husband felt the same way, having replaced NOK with the meek and subservient Gen. Musa Khan. Insecure Ayub had earlier replaced widely popular Gen. Azam Khan in East Pakistan too, with another sycophant Monim Khan.

NOK’s reputation for ruthlessness created many myths: one was allegedly a slap to the principal of King Edward Medical College, a highly respected surgeon of Lahore, who had annoyed the all mighty Governor, by not approving a student’s migration to his institution; another, widely believed allegation was the attempted murder of Maudoodi Sahib of JI. Jahandad Khan who has devoted many pages in his memoirs to NOK, is convinced that both rumors were baseless, probably spread by the Governor’s political opponents and there was no shortage of them. NOK was an admirer of Amir of JI and once told Dr Toosi, a personal friend, of his frustration with Ayub who used to urge him to do something about “this dangerous Maudoodi”. Some time ago, this writer approached the physician son of the alleged victim of the slap, to clarify that incident. I have yet to receive a reply.

NOK’s sons were educated abroad but none had the talents of their father. What they did inherit from him was his weakness --the feudal mindset. He had been a harsh father and husband; there had been discord within the family. His return to Kalabagh, set in motion an unfortunate series of events that led to his tragic death.

NOK had two daughters; one was still single. For some time, he had been mulling over the proposal of Dr Tahir Toosi who was the son of a close friend of his. This young man was well educated and handsome but he was a Kashmiri and that was not acceptable to the Nawab’s family. This started a friction between him and his sons who were supported by their mother and maternal uncle. The sons had another concern too. NOK had given some indications that he was fed up with his sons and was considering transferring his property directly to one of his grandsons. This was too much for his sons. It is said 'whom the gods wish to destroy, they throw a bone of property to them.' And so, one day when NOK was relaxing in his famous guest house, where over the years he had entertained many rich, powerful and influential guests, he was murdered in cold blood by no other than one of his own sons while he was enjoying a movie. Malik Asad allegedly shot his father, point blank. With the much feared NOK dead, the whole family stood united behind Asad. NOK’s dead body was disposed off in a hurry; it was taken to the graveyard in a trawler and buried overnight - no funeral prayers were allowed.

Thus ended the life of NOK whose word was once law of the land. There was a trial. I recall that M. Anwar, the renowned attorney from Lahore, pleaded for prosecution in a case that made headlines for months. At the end, nothing came of it. Malik Asad went scot free. In his memoirs, Jahan Dad hints at some collaboration between NOK’s family and Ayub government who may have been relieved to see the end of someone who knew too much. But God has his own way of dispensing justice. Years later, Malik Muzafar, NOK’s eldest son who many believed to be the mastermind behind his father’s murder, was gunned down in broad daylight in Kalabagh by his political opponents, the Baghochi Mahaaz.

As I think of NOK, my mind goes back to that famous TV play of the late 70’s, Waris. The main character of that play was Chaudhry Hashmat, an old-fashioned feudal, who found it hard to accept change. At the end of the play, Chaudhry Hashmat preferred to be drowned in flood, rather than leave his ancestral home. NOK was also a representative of old times and feudal culture who found it hard to change with time. His way of life was fading away but he was clinging to the old obsolete values. Ayub had made good use of him to keep West Pakistan under control but times had changed. In Ayub’s government, NOK represented the pro-west faction; the other was pro-China group, represented by popular Bhutto and Altaf Gauhar. Ayub may have felt that NOK had become a liability and let him go.

NOK was a well-read person. A visiting delegation from Imperial Defence College (UK) once called on the Governor. After the meeting, one of the delegates remarked that the most well-informed person that they had come across in Pakistan on international affairs, was NOK. That surprised many but not those who knew of NOK’s love of reading; he kept himself well versed in international affairs. At a banquet given in her honour, Jacqueline Kennedy asked him a question about a fruit that she had not seen before. Now NOK was no absentee landlord; he was a well informed, experienced farmer who had over the years taken a keen interest in his farms at Kalabagh. His discourse regarding guava so impressed the first lady of USA that she said: “I am going to ask my husband to make you his agricultural advisor.”

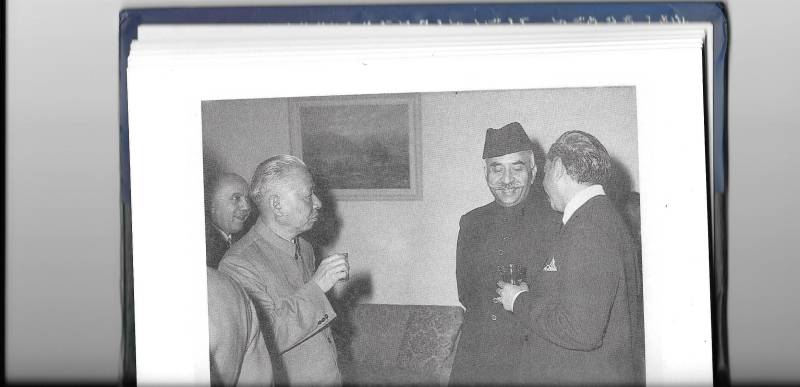

I have a picture in which NOK, the Governor of West Pakistan, is seen chatting with a young Z A Bhutto, then the favourite minister of Ayub, while the visiting President of China, Leo Chao Chi is standing by. All three seemed to be having a jolly good time. Who would have thought that within a few years, all three would fall from power and meet tragic, violent deaths. But then, such are the ways of this world! Rahe ga naam Allah Ka.